11 Crucial Ways to Combat Impact Knee and Ankle Injuries in Gymnastics

Impact knee and ankle injuries, unfortunately, are something that plague many gymnasts. This is mainly because young athletes are exposed to massive impact forces that may reach 8.8x – 14.9 times body weight, 1000’s of times per month, and pretty much year round (read more about the latest science here). Peak bone on bone impact ankle forces have been recorded by Bruggerman at 23 times body weight, which is mind-blowing (biomechanical studies can be found in this book).

As this recent 2018 Systematic Review of Gymnastics Injuries continues to show, lower body injuries are skyrocketing in gymnastics, ranging from recreational levels to Olympic levels, creating much time missed from practice and massive health problems.

Issues like stress fracutres, ankle sprains, growth plate inflammation, ACL or meniscus tears, Achilles injuries, and overuse cartilage break down are seen throughout all levels of gymnastics. These injuries all have a common overlap in being “impact” based.

Other factors like not tracking impact workloads, equipment changes, limited ankle or hip mobility, landing short, technique issues, nutrition, and lacking leg strength also play a role.

Table of Contents

What Knee and Ankle Injuries Do Gymnasts Deal With?

Younger gymnasts typically get Sever’s Disease or Osgood Schlatters (medically named calcaneal and tibial apophysitis) which is essentially inflammation of a heel or knee bone’s growth plate (more research articles here, here and here). When this occurs at the lower kneecap, it’s called Sinding-Larsen-Johannson Syndrome, and when at the outside foot bone it’s called Iselin’s disease.

These impact injuries tend to happen because the growth plates are open, and the boney tissue within them is mainly cartilage, not fully fused bone. This causes them to not tolerate loading well, and it then becomes a huge point of stress during impact.

Once growth plates fully close and gymnasts get older, the forces tend to shift to the actual Achilles tendon, patellar tendon, or internal structures of the joint like the meniscus or ligaments. They also tend to become more intense as gymnasts do harder skills, and train more hours per week. Through repetitive bouts of trauma, these injuries usually manifest as

- Chronic insertional or midstubstance Achilles/Patellar tendinopathy (research here, here, here, and here)

- Mixed impact injuries that include talar dome or navicular stress fractures (research review in ballet dancers here) or talar dome OCD (Osteochondritis Dessicancs research here)

- Full Achilles, ACL, or Meniscus tears (research here, here, and here) as repetitive microtrauma overtime or one sudden event causes full tissue failure that may require surgery.

How to Help with This Growing Problem in Gymnastics

I have unfortunately treated or consulted with hundreds of gymnasts for various knee and ankle injuries. The only upside of this is that it has allowed be to see a lot of data and emerging trends for helping them.

Whether injuries come in the form of young gymnasts who suddenly get Severs, college or elite gymnasts struggling with chronic tendinopathy and boney stress fractures, or any athlete who suffers a full ACL tear, there are many overlapping principles everyone in gymnastics can apply in their daily training.

I honestly think we see the same version of an injury along a spectrum, depending on how mature a gymnast is. Sever’s when a gymnast is young may become Achilles tendinopathy or a stress fracture when in high school, which may become a full Achilles tear in college. Osgood Schlatters when they a gymnast is young may become patellar tendinopathy or “patellofemoral syndrome” (not a great term at all) when they are in high school, which may then become a full meniscus tear in college.

It’s beyond the scope of this article to talk about full Achilles or ACL tear rehab (if you are interested check out great research articles here and here). For the 90% of knee and ankle overuse injuries that most people face, here are 11 concepts to help I teach pretty much everyone.

1. Temporarily Reduce Workloads and Impact Volume

Honesty is the best policy, so let’s just embrace reality and deal with it. The main reason gymnasts get so many impact ankle or knee injuries is because they are simply doing too much, too fast, and are kids who have not yet fully matured.

Many people ask me about the best exercises and stretches to make heel or knee pain go away, usually only once someone’s injury has progressed really far and usually with a competition approaching. It’s unfortunately much more complicated than that.

The truth is that all these injuries come due to a mismatch between tissue load and tissue capacity. Sudden spikes in workloads (like suddenly increasing the number of hard landings in gymnastics or full routines), as well as excessively high chronic workload (multiple high intenstiy training days in a row), may be problematic for injury risk (research here and here). Don’t get me wrong, we need to train these things. But we need to take very common sense / scientifically supported approach, and one that has constant communication with how gymnasts are feeling.

In order to have a hope of long-term solutions, we have to temporarily reduce impact volume when pain presents, and then rebuild loading tolerance slowly though strength and conditioning and graded impact exposure. At first, this will probably be a few weeks of no impact at all to allow healing. Then it means slowly introducing load through basics, tramp or Tumbl Trak, soft mat landings, and reduced numbers. Then finally it can progress back to hard landing, full tumbling/dismounts, and a return to higher numbers.

2. Diagnose and Get Medical Care Quickly

The important background to this is that a gym must have a culture of trust and communication so that gymnasts actually feel comfortable speaking up about pain.

If that issue is not addressed first, and unhealthy environments or coach/parent pressure exists in some form, delayed care is inevitable and it makes finding solutions much more challenging. While I have also worked with gymnasts who are just stubborn to speak up for themselves, or possible are trying work around skill fears, these cases are the minority. The conversation I have with gymnasts is very different if they had pain for 4 days versus 4 months.

If injuries negatively impact practice for more than 3 days while trying to modify things, it’s best to seek out a medical doctor to rule out serious issues, and then a rehabilitation professional (preferably one that knows about gymnastics). This is to not only great treatment, but also a home program and full movement evaluation to look at other areas contributing to the issue.

3. Be Patient

I know we are three suggestions in, and I haven’t said anything about exercises yet. It’s intentional, because these are the real issues no one wants to have a tough, but necessary, conversation about.

In gymnastics we work with kids who are growing like weeds and every 6-8 months have completely different bodies. The long bones like the femur and tibia grow much faster than the muscles and tendons can keep up with. As much as we wish 1-2 days of rest would make the pain go away, it’s better to change our perspective into the frames of weeks to months, even when properly managed early.

4. Manage Soft Tissue Daily (Manual Therapy and Stretching)

The nature of gymnastics requires many hours per day of toe pointing (plantarflexion) legs together (adductors) and knees straight (extension). This ranges from having good form of toe point or tight legs constantly, to running, to jumping, to actual skills or tumbling.

When stacked on top of the massive eccentric trauma from landing forces (remember up ot 15x body weight), the legs take quite a toll. Over time training may cause adaptive stiffness in the muscular tissue that reduces range of motion, as has been shown my by friend and mentor Mike Reinold in baseball (more research here)

First, toe up motions (dosiflexion) and hip extension should be screened for, and then from there daily foam rolling and wall stretching should be done. Research suggests 2 x 30-60 seconds of each, done 5-6x/week, is ideal (check out those review studies here and here)

5. Use Ice Baths and Compression Nightly

Bone pain and acute Achilles/Patellar pain is beyond brutal. So if you are a coach or parent, definitely have some empathy. Nightly cold water soaks are recommended to help manage the pain, despite mixed research reviews on reducing inflammation (great article on my buddy Mike Reinold’s site here on the icing science debate). In my opinion, we are more looking to reduce the sensitivity to movement as one part of the overall treatment program.

On that note, active movement and compression have been supported to help manage inflammation (research here). So, ice may help reduce pain, and then help someone move more comfortable to manage pain/loading tolerance. Similarly, compression sleeves may also be helpful to wear. Dr. Sands has a fantastic Recovery talking about these concepts in this book here.

6. Land Properly

As mentioned, the landing forces are truly massive in gymnastics. I have talked about this before (full article here), but the simple reality is that gymnastics must change the way that it teaches kids to land.

Landing with the feet/knees together, with an upright torso, hips tucked under, and mainly using the knees, is not the ideal way to absorb force.

Research continues to show this is not only reducing landing stick performance, but also is a huge risk factor to many commonly seen knee and ankle injuries (read more here, here, and here)

This is opposed to the feet hip-width apart, knees in line with the hips, and proper deceleration through squat patterns (trunk and tibia angle parallel and hip to around 30 degrees flexion). This is an essential part of the rehabilitation process for any gymnast I work with.

This more squat based movement pattern allows much of the force can be shifted into the leg muscle tissue that is designed for this force absorption, like the hamstrings, quads, glutes, and core. This is a critical component of helping the forces of gymnastics go through the entire body equally, and ideally the hips/core, rather than only the Achilles.

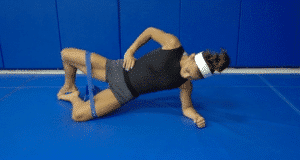

7. Slowly Rebuild Knee and Ankle Joint Strength Following Injury

Following the reduction of pain and proper management, rebuilding the local knee/ankle strength and ability to tolerate force is very important. Rushing back to gymnastics is one of the most common mistakes I see. We have to use formalized principles of strength and conditioning, as well as workload research, to slowly increase a gymnasts tolerance to impact (more here and here).

I want to be really clear here, it’s important that we push gymnasts and stress them. This is not about wrapping an athlete in bubble wrap and always pulling back. The body adapts when the optimal dose of stress is given and followed by the optimal dose of recovery.

I like to give gymnasts cube hops, single leg medball rebounders, and single leg mirror landing drills to slowly regain their strength and practice proper landing technique. I also use a ton of general plyometrics progressing from small (bunny hops) to medium (depth jumps double and single leg) to large (multiple bounding jumps single leg). This is then built into a full plyometric and return to sport and physical prep program that I will cover below.

8. Slowly Rebuild Impact Volume Following Rehab

This is by far one of the most important areas to enforce, regardless of if the pain is gone. The easiest way to re-irritate the Achilles or knee is dive back into all hard surfaces and high impact workloads. Back to the studies again, we must use progressive overload and concepts of periodization (research here) to increase tissue tolerance before we go back to big gymnastics skills.

Again, I want to be clear that we do need to stress the knee or ankle appropriately. I see just as many gymnasts get reinjured because they are not stressed enoug in rehab for those that are over stressed in training.

Workload and\ injury research has outlined that doing nothing or not exposing the body to stress may not be the ideal approach. I design programs where the gymnast starts on soft/tramp surfaces 3x/week and counts the number of impacts, then slowly progresses to medium surfaces and finally hard surfaces, over 4 weeks. I also tell them that pain levels of 3/10 are the limit, and soreness can not last more than 24 hours, or else they pushed it too much.

Slowly progressing the surface, and objectively counting/increasing the volume per session with at least 24 hours in between is essential. Here is a picture from a 6 week program I made for a gymnast who had injuries to both legs to illustrate the point.

9. Correct Technical Issues (Steep Take off and Landing Short)

This is something I think about way more now than 5 years ago, thanks to being able to learn from some fantastic gymnastics coaches, and asking their opinions about why so many injuries occur. Very steep take-off angles on the floor are definitely something to consider changing. I have embraced a more “hip whip” technique that elite coaches I have talked with promote. This is one where the arms lead the way into a tight arch, and the hips are used to generate rotation. I have found this be very helpful to reduce Achilles stress over very steep take-off angles, although I know it’s not always possible)

The other more obvious piece, although it’s shockingly not addressed, is that gymnasts simply need to stop landing short and destroying their ankles all the time. Mistakes obviously happen here and there, but the reality is that far too many gymnasts are being allowed to land very short on a daily basis. Coahes and athletes must instead take a step back to have a tough conversation, hold skills that are not ready, and rebuild basics/fundamentals. Health first, gymnastics second. If you don’t do this, the risk of reinjury and long term problems skyrocket.

10. Build Leg Strength with Physical Preparation Programs

This goes in line with the comments on landing technique, taking force in the hips, and patience. Gymnastics is harder than it ever has been, and the skills being done by younger gymnasts is baffling. A huge chunk of time per week should be dedicated to strength, conditioning, and physical preparation if gymnasts want to survive such high impact forces.

I won’t dive into the background, but this must come with an overhaul in the way we approach gymnastics strength programs. We must be open to a hybrid model where gymnasts lift weights and do bodyweight work, embrace periodized methods, use ideal work to rest ratios, do less meets and more general training, and possibly even have a relative offseason. Without these changes, we will keep seeing shockingly high rates of ankle (and all other) injuries.

Read more about these thoughts here and here, and check out a full free hour lecture on Gymnastics Strength Programs here.

11. Track Growth

Ankle, knee, and many other growth plate injuries tend to come on strong when periods of rapid growth are going on. Keeping a proactive measure of this growth can be really helpful in forecasting times of elevated risk, and consequently time when people will inevitably need to pull back on training. Check out this article where I talk about how to do this, as well as the research behind it.

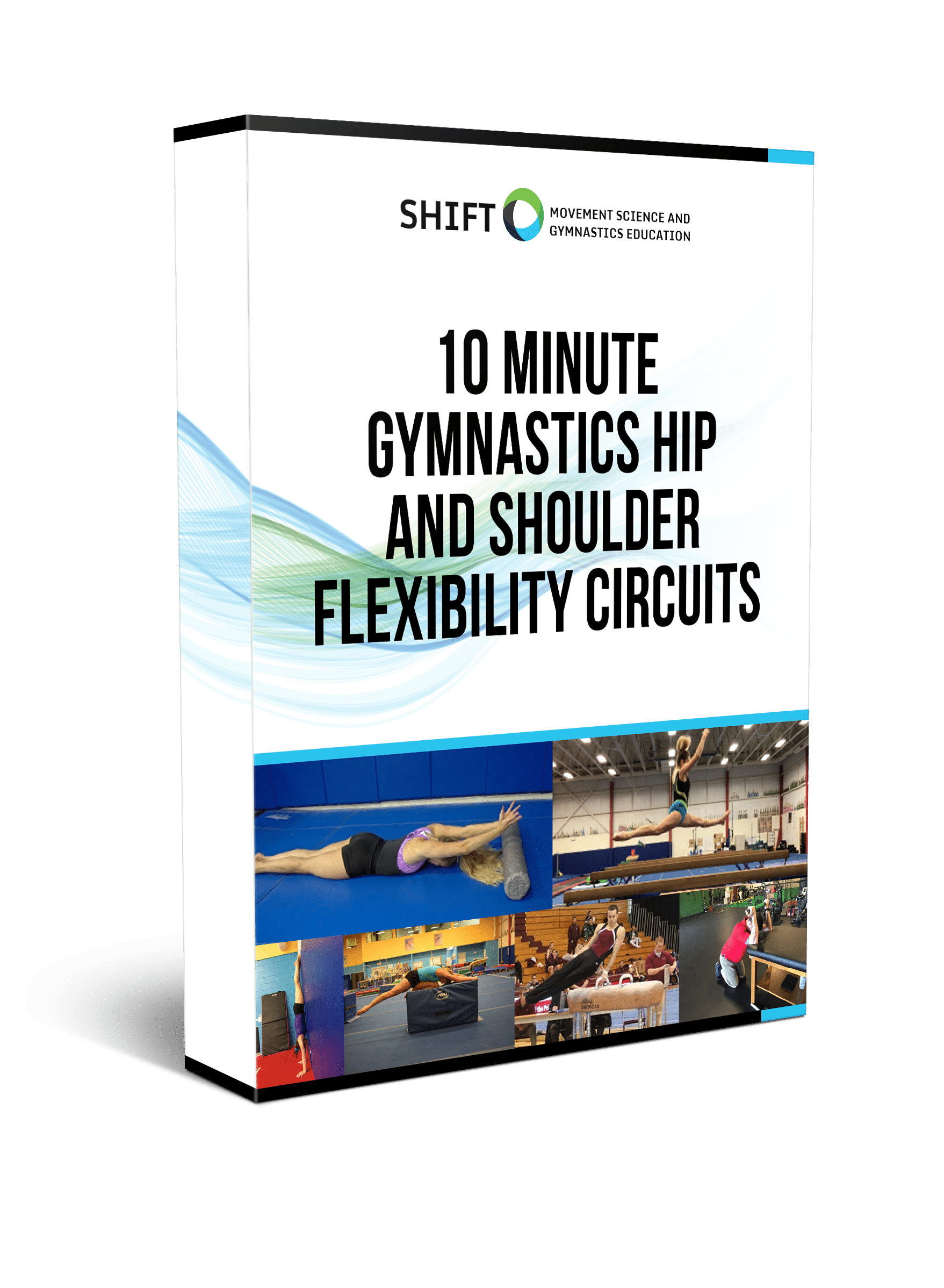

Want to Learn More? Download My Free Gymnastics Pre-Hab Guide, 10 Minute Flexibility Circuits, or Gymnastics Medical E-Book

If you are looking for more specific flexibility or prehab programs, you can download these free worksheets I made over the summer to help people out. The “10 Minute Flexibility Guide”, and “Gymnastics Pre Hab Guide” are full of specific circuits, stretching, strength, and injury prevention exercises I use every day. For medial providers who want to know all my thoughts on lower body injuries and rehab, my Gymnastics Medial E-Book has erything you need. They also have full printable worksheets to hang up in the gym, and exercise video tutorials to learn from.

Download My New Free

10 Minute Gymnastics Flexibility Circuits

- 4 full hip and shoulder circuits in PDF

- Front splits, straddle splits, handstands and pommel horse/parallel bar flexibility

- Downloadable checklists to use at practice

- Exercise videos for every drill included

Download SHIFT's Free Gymnastics Pre-Hab Guide

Daily soft tissue and activation exercises

Specific 2x/week Circuits for Male and Female Gymnasts

Descriptions, Exercise Videos, and Downloadable Checklists

The Gymnastics Medical Injuries Guide

- Understand the most common injuries in male and female gymnastics, why they occur, and how to prevent them

- Read about the most current science on injuries and rehabilitation in gymnastics

- Get tips on the latest injury risk reduction and rehabilitation practices

We take our privacy seriously and will never share your information. Click here to read our full privacy policy.

Concluding Thoughts

Obviously, there are many more factors beyond this like equipment changes, biomechanical issues, or individual anatomy issues that may be factors. But, I wanted to keep this more general to try and help as many people as possible. If there are more specific issues, the best thing to do is seek out medical management as well as sports rehabilitation specialists and experienced gymnastics coaches for more advice. For now, I hope this helps!

Dave

Dr. Dave Tilley DPT, SCS, CSCS

CEO/Founder of SHIFT Movement Science