5 “Must Hit” Milestones For Gymnastics Shoulder Rehabilitation

The rates of shoulder injuries, especially on the men’s side, are staggeringly high in our sport. A systematic review from Thomas in 2019 showed that shoulder injuries can be up to 42.8% and 30.8% of all injuries for male and female gymnasts, respectively. This was in comparison to an average of 20% in other sports. Another systematic review by Campbell in 2019 were in line with this, They suggested that male gymnasts had mostly upper limb injuries. They also outlined that risk increases as competition level increases.

A 2018 review by Gil of just shoulder injuries in 5 years of NCAA gymnastics reported that shoulder injuries had the highest rate of requiring surgery. Another 2019 systematic review of 15 studies by Hinds looked at the types of shoulder injuries in women’s gymnastics. From most common to least common, they reported rotator cuff pathology, labral/SLAP pathology, instability related issues (MDI, subluxation, dislocation) and then contusions/strains from falls as most common.

If you look at the sport, it makes sense. Hume, Bradshaw, and Bruggemann report that forces on the upper extremity have been measured at 1.5x -4x body weight for vault, 3.9x body weight for high bar, 9.2x body weight for rings, and 2.0x body weight for pommel horse (book source).

Looking at repetition numbers, in 2010 Burt et al showed an average of 1-2 upper extremity impacts over the course of practice. And to be honest, these forces are probably drastically low in the literature as they do not measure the most difficult skills or real-life training conditions.

Having treated and worked with well over 500 gymnasts for shoulder injuries at this point in my career. They have ranged younger to older athletes, recreational to Division 1 NCAA and elite gymnasts, and from basic strains to very complex surgical cases. I’ve been fortunate to have really good mentors in this department, as Mike Reniold and Lenny Macrina are internationally renowned for shoulder care. Looking back on these casees and the mentorship I’ve had, I wanted to offer 5 “Must Have”

Table of Contents

1. A Period Of “Putting Out The Fire” With Workload Modification

Without a doubt, one of the most important (but hardest to implement) parts of successful shoulder rehab in gymnasts is the initial workload modification period. If there isn’t a plan in place to really modify the things that bother gymnasts shoulder the most, and modify them for a period of time, the risk of flare-ups is high.

My number one piece of advice is to approach this conversation with empathy and genuinely wanting whats best for the athlete. I think sometimes as medical providers we sometimes unintentionally deliver the need to back off in the wrong way. It’s crucial that to gain trust, and also have a good long term outcome, we explain to a gymnast that backing off now and changing training can mean getting back to training faster, fully, and with a better chance of reaching 100% percent or more.

Get a good picture of what skills or events trigger shoulder pain, as well as daily life activities. Make a plan to back off those things, but also focus on what they still can do. Fill in extra strength or core/lower bodywork, make cardio programs that don’t involve the cranky shoulder, and more. There is plenty to do, and approaching things with empathy and optimism is key.

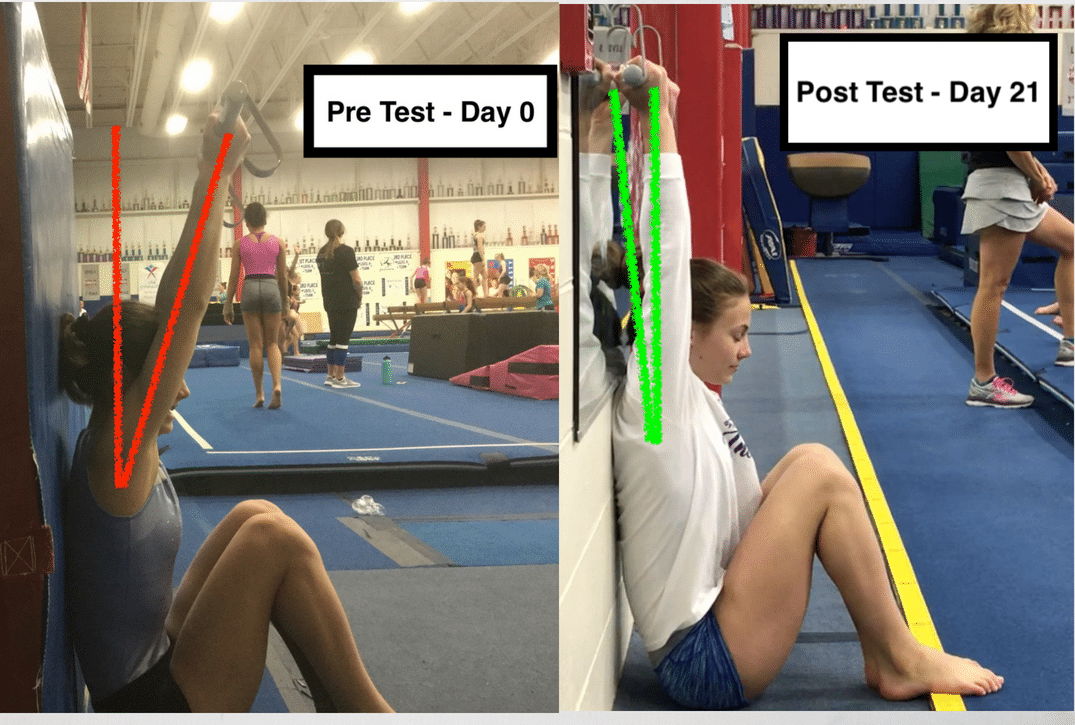

2. Restore Full “Gymnastics” Mobility

It’s really important to remember that the average amount of shoulder mobility for the general sporting population is far from what gymnasts. Reinold 2013 and Wilk 2010 both stress how important this is in overhead athletes, and it applies even more to gymnasts.

I’ve made the mistake of not restoring mobility fully, and it always came back to haunt me later down the road during advanced strength or return to the sports program. First things first, we have to make sure our assessments are super valid and specific. Here is a short video on assessing overhead mobility.

Gymnasts also need to get back a significant amount of external rotation and internal rotation at 90d degrees of elevation. This is less for sports requirements, say like baseball, but more to make sure capsular mobility and soft tissue have been fully restored. Most gymnasts are naturally lax and isn’t always a problem, but this is especially true if someone had surgery. External rotation allows for proper middle, and inferior glenohumeral ligament motion as well as latisimus doris, teres major, and subscapularis soft-tissue motion. Internal rotation allows for proper inferior glenohumeral ligament (specifically the posterior band) and posterior capsule motion, as well as teres major and posterior rotator cuff soft tissue motion.

Lastly, shoulder extension is absolutely critical for male gymnasts to get back. It is required for the front swing of parallel bars, pommel horse skills, jam skills on high bar, and more. Most of this motion comes from good pec major/minor soft tissue flexibility, as well as the areas noted above.

As mobility milestones go, we definitely need symmetry between sides. Some gymnasts are naturally stiff, and lack overhead motion bilaterally. But, I generally try to see

- 175 – 185 degrees minimum of overhead elevation

- 100-110 degrees minimum of external rotation at 90 degrees of elevation

- 50-60 degrees minimum of internal rotation at 90 degrees of elevation, stabilizing at the scapula

3. High-Level Rotator and Scapular Strength

The forces of gymnastics, and all sports, are massive. I think it’s a myth and common mistake that people think we shouldn’t ever push the rotator cuff and scapular muscles to a high degree. The main thought here is that because they are smaller and stabilizer muscles, they should not be trained in a hypertrophic setting. I think this is where a lot of people fall off track.

If the shoulder forces in gymnastics are 2, 4, maybe 8+ times body weight, it’s crucial that we push these muscles into hypertrophy paradigms. If this doesn’t occur, the dynamic stabilizers like the rotator cuff and other muscles may not be able to buffer the stress, and it may get shifted to the passive tissues like the joint capsule, labrum, or bone. Furthermore, we may start to see instability as the glenoid is very shallow and doesn’t have great inherent stability.

I recommend that people have gymnasts do the following exercises that are supported by great EMG research. Papers by Reinold in 2004, 2007 and 2009 looked at this.

Patients should be starting with lower weight, set/reps of 2-3 sets of 10-12, and more frequently in the initial rehab phases. Then, as rehab progresses they can increase the weight, change the set rep range to 3-4 sets of 6-8, add eccentric focuses, and bump to 3x/week.

- Sidelying Dumbell external rotation

- Prone I, T, and Y

- Progressing to Prone U (ER at 90 degrees)

- Standing Full Can

- Standing Band ER/IR at 0 degrees

- Progressing to Band ER/IR at 90 degrees

You can check out how I prescribe these exercises here

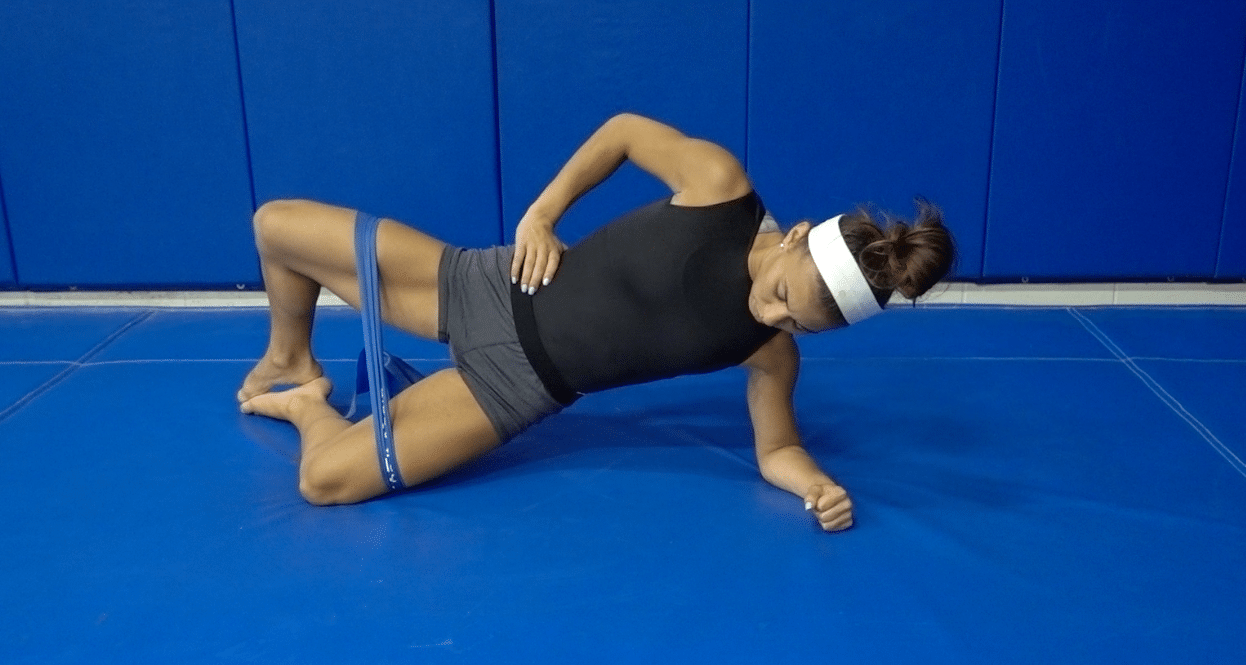

4. High-Level Dynamic Stability

Similar to high-level mobility and strength, the papers above also outline that high-level dynamic stability is another milestone we have to reach. Along with inherent strength to handle forces, the shoulder joint also needs a high level of co-contraction and coordination between muscles to maintain good joint centration. Force couples between the infraspinatus/teres minor and the subscapularis, the middle/lower trap and upper trap, the supraspinatus and deltoid, must all be well synchronized.

Early in the rehab, open-chain rhythmic stabilizations in mid-range are a great way to achieve this, which you can learn about in this short video.

- Front, back, and sideways bear crawling

- Heavy suitcase carries, 90-90 bottoms up shoulder carries, and overhead rack carries

- Static hangs progressing 1 arm hangs, and weighted strength

I look for gymnasts to be able to tolerate these high-level exercises in both compression and traction as a milestone in combination with the points noted above.

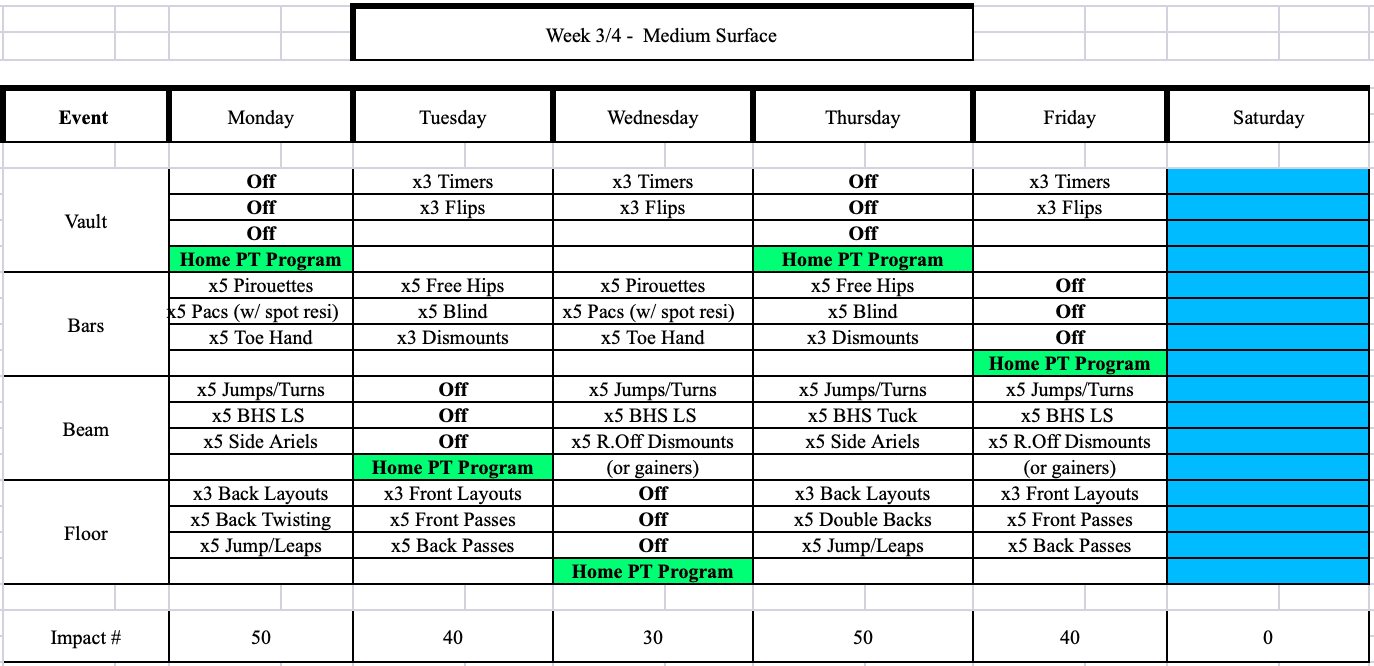

5. A Gymnastics Specific Return To Sports Program

Lastly, one of the most critical phases of shoulder rehabilitation for gymnastics is the return to gymnastics phase. It’s often tough because the nature of gymnastics with so many skills, surfaces, and loading is overwhelming. I generally like to get all the skills a gymnast does, how many days per week they practice, and their goals first. From there, I make programs that over 4-8 weeks. I usually start with 3x/week, and increase the demand every 1-2 weeks, based on:

- Surface – moving from soft, to medium, to hard surfaces

- Tumbl Trak, to Rod Floor, to Hard Floor

- Skill Force – moving from basic, to intermediate level, to high-level skills

- Basic swings/giants on bars, to 1 arm skills like pirouettes or blinds, to high force skills like releases and dismounts

- Total Numbers – that generally break up into compression/traction, and go from low, to medium, to heavy force.

- 3x/week of lower volume, to 3x/week of moderate volumes, to 5 days of higher volume

As far as milestones go, a gymnast must be able to safely move sequentially through a more basic phase with minimal symptoms and no adverse effects before graduating to the next phase.

Want To Learn More?

The reality is that these things are important, but just the tip of the iceberg. There are so many things that have to go well in the acute, subacute, advanced, strength & conditioning, and return to sport phases. I’ve made the mistake of not knowing these things in the past, only to have gymnasts who keep struggling with pain, reinjury, or limited progress. A lot of people are confused and a bit overwhelmed when it comes to shoulder, elbow, and wrist rehab for gymnasts.

I have been putting together a huge course that aims to help people with a step by step guide to these injuries. In light of the terrible coronavirus situation we’re all stuck in, I’ve worked like crazy to it up. I’m excited to say, “Recent Advances in the Evidence-Based Evaluation and Treatment of Upper Extremity Injuries in Gymnastics” is officially open for enrollment. If you want to learn more, check it out here!

Recent Advances in the Evidence-Based Evaluation and Treatment of Upper Extremity Injuries in Gymnastics

Again, I hope during the coronavirus you are safe, healthy, and keeping a good headspace! Take care,

– Dave

Dr. Dave Tilley DPT, SCS, CSCS

CEO/Founder of SHIFT Movement Science

References

- Thomas RE., Thomas BC. A systematic review of injuries in gymnastics. Physio Sportsmed. 2019 Feb;47(1):96-121

- Campbell RA., et al. Injury epidemiology and risk factors in competitive artistigymnasts: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2019 Sep;53(17):1056-1069. Epub 2019 Jan 22.

- Hart E., et al. The Young Injured Gymnast: A Literature Review and Discussion. Cur Sports Med Rep. 2018;17(11):366-375

- Wolf SF., Labella CR. Epidemiology of Gymnastics Injuries. In Sweeney E. (Ed) Gymnastics Medicine: Evaluation, Management, and Rehabilitation. Springer 2020; 15-26

- Gil JA., et al. Characteristics of Operative Shoulder Injuries in the National Collegiate Athletic Association, 2009-2010 Through 2013-2014. Orthop J Sports Med; 2018: 6(8)

- Hinds N., et al. A systematic review of shoulder injury prevalence, proportion, rate, type, onset, severity, mechanism and risk factors in female artistic gymnasts. Phys TherSport. 2019 Jan; 35:106-11

- Bruggemann GP., Hume PA. Biomechanics related to injury. In Handbook of Sports Medicine: Gymnastics. 2013. Wiley-Blackwell

- Andrews, J., Reinold, M., Wilk, K. Current Concepts in the Evaluation and Treatment of the Shoulder in Overhead Throwing Athletes Part 2: Injury Prevention and Treatment. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach 2(2) 2010.

- Wilk KE, Macrina LC, Reinold MM. Nonoperative rehabilitation for traumatic and atraumatic glenohumeral instability. North Am J Sports Phys Ther 1(1):1631, 2006.

- Reinold MM., Escamilla E., Wilk KE., Current Concepts in the Scientific and Clinical Rationale Behind Exercises for Glenohumeral and Scapulothoracic Muscualture. JOSPT 2009; 39(2):105-11

- Reinold MM., et al. Electronic Analysis of the Rotator Cuff and Deltoid Musculature During Common Shoulder External Rotation Exercises. JOSPT 2004; 34(7):385-394

- Reinold MM, Curtis AS. Microinstability of the Shoulder in the Overhead Athlete. IJSPT. 2013l 8(5) 601 – 616

- Edwards PK., et al. A Systematic Review of Electromyography Studies in Normal Shoulders to Inform Postoperative Rehabilitation Following Cuff Repair. JOSPT 2017; 47(12):931-944

-