Understanding and Combatting the Elbow Injury Epidemic in Gymnastics (Part 3)

Over the last few weeks, I have been sharing some of my thoughts on elbow injuries in gymnastics. If you haven’t read Part 1 (find it here) and Part 2 (find it here), I would be sure to check those out. Today, I’m going to close out the article series with 2 more hugely important points about gymnastics strength training and early detection of red flags.

Table of Contents

7. Don’t Fear The Appropriate Use of External Weight During Gymnastics Strength

At the most basic level, overuse elbow injuries like OCD (and all other overuse injuries) come down to an equation of the tissue load being more than the tissues capacity to handle it. The ideal scenario during training is that we expose the elbow joint to an appropriate amount of stress (back handsprings, strength, other skills), and then allow the proper time/environment for recovery. When this balance of work to rest is reached, the body adapts and grows stronger to protect itself. This is a beauty of the human body.

However, in the case of an elbow overuse injury like OCD what often happens is either we are overloading it past its load bearing capacity, or not giving the elbow enough recovery time between bouts of impact. As this new 2017 research paper outlines, the OCD lesions gymnast get tend to be more weight bearing in nature and on a different area of the elbow joint than baseball players, which is important to understand in relation to training programs.

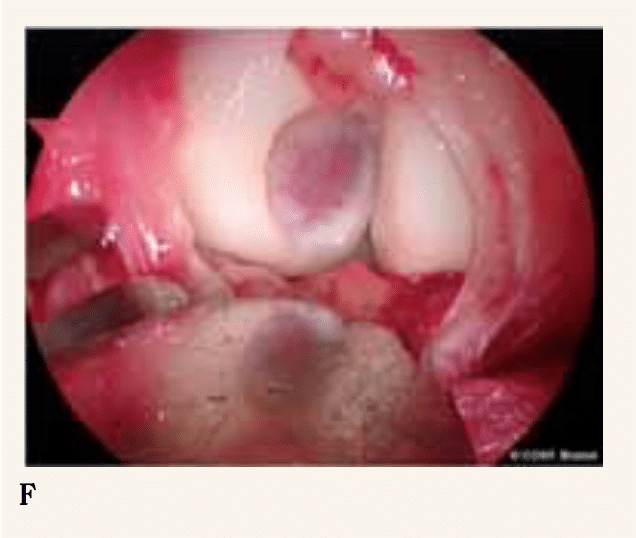

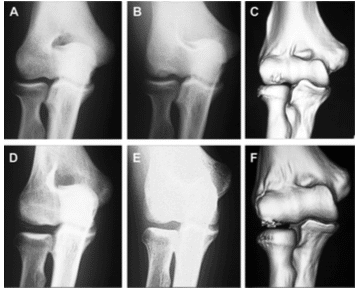

This is often times where the term “fatigue injury” comes into play. The bones of the elbow and cartilage in this area that are not fully developed, especially in a skeletally immature young gymnast, start to wear down creating pain, inflammation, an inability to bear weight, and if bad enough irreversible cartilage/bone damage that may require surgery. Sorry if this picture below is a little graphic, but it shows the OCD lesion and bone break down really well.

From Bae and Hale 2016, example of elbow joint breakdown and Grade IV OCD lesion

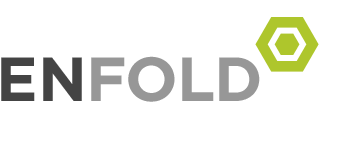

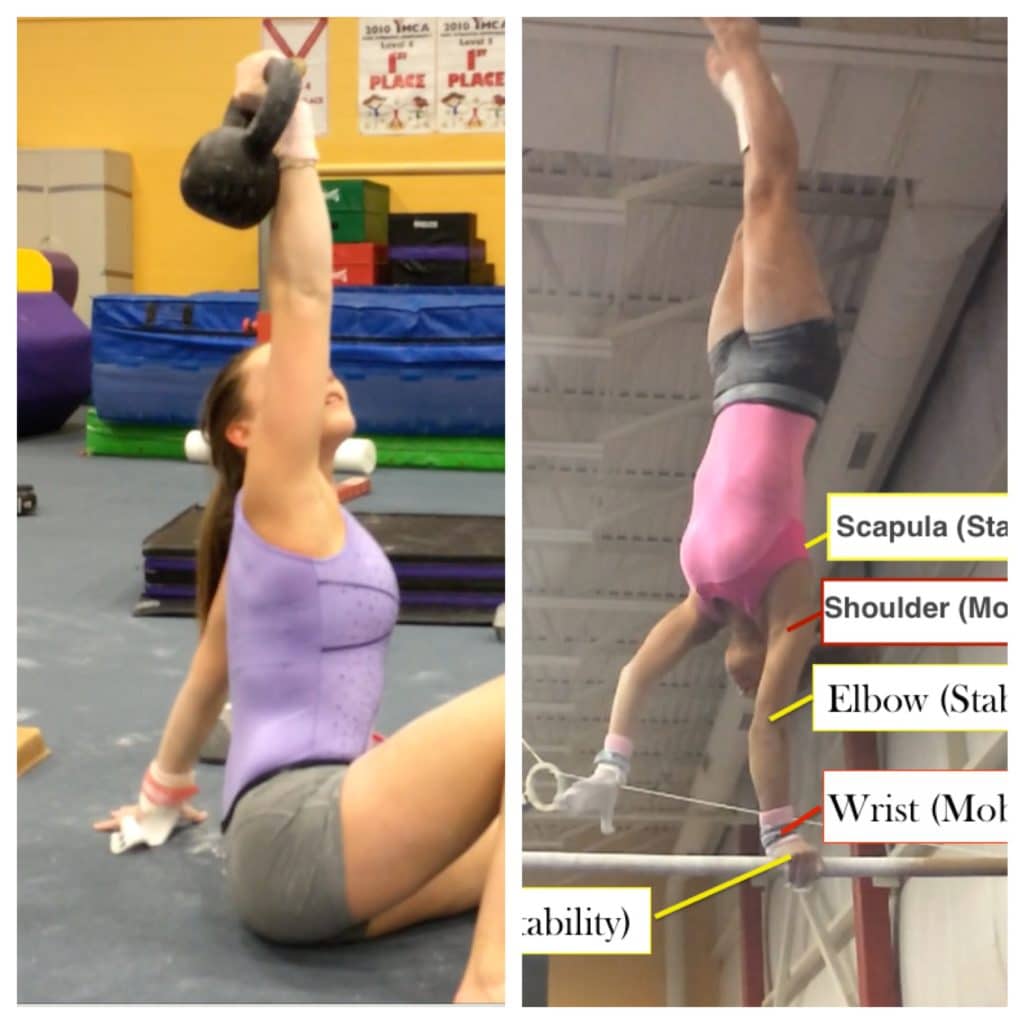

This is where the use of external loading during gymnastics strength programs fits in. Using appropriate external load through dumbells, kettlebells or barbells can help close the gap between how much an elbow joint can handle (capacity) and how much it is being stressed.

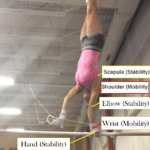

Through a well planned, periodized strength program, theoretically, we can help build up the load bearing ability of inherently non-weight bearing joints of the shoulder, elbow, and wrist. This will allow these joints to develop more ability to handle high forces before gymnasts are ever introduced into high volumes or impact skills (beam BHS, pirouettes, and blinds on bars, front giants, high force vaults like Yurchenko’s).

I think many people don’t see that the movement patterns during exercises like 1/2 kneeling presses, Turkish get-ups, and push presses are pretty much exactly the same patterns seen in blind changes and impact vaulting/tumbling.

Although there are hundreds of great upper body exercise variations, some of my personal favorites that we use primarily in summer training are

1/2 Kneeling Dumbell or Kettlebell Presses

Turkish Get Ups and Overhead Carries

Renegade Rows

Dumbell or Kettlebell Push Presses (Think Partial Body Weight Handstand Push Up)

Obviously, these are in conjunction with the more traditional gymnastics exercises such as handstand pushups, stalders/presses/cast handstands, push-ups, pull-ups, rope climbs, and so on. Again, external loading is just one part of our strength program, not the entire thing.

I truly think that a change in our culture to be open to the proper use of external loading during gymnastics strength is one of our best tools to combat the insanely high rate of elbow injuries in gymnastics. The topic of which exercises, the loading paradigms, periodization, and program design are a much larger topic for another time. However, I have quite a bit of faith that this will be the future of gymnastics in the next 5-10 years.

In addition to strength programs, modulating load through objective counting of skills (“make 5 beam series, but don’t go over 7 attempts”), or rotating event focuses so that every event does not include heavy impact in the elbows is also another viable option. Doing Yurchenko’s on vault, shoot overs on bars, tumbling on floor, and series involving back handsprings on beam can easily put the elbow impact count into the 100’s for a day. Switching up one event focus and giving objective numbers can go a long way to making a dent in that amount of total loading.

Remember if you like this information, you can download every thing I look at for Gymnastics Injuries completely for free. Here it is,

The Gymnastics Medical Injuries Guide

- Understand the most common injuries in male and female gymnastics, why they occur, and how to prevent them

- Read about the most current science on injuries and rehabilitation in gymnastics

- Get tips on the latest injury risk reduction and rehabilitation practices

We take our privacy seriously and will never share your information. Click here to read our full privacy policy.

8. Know Red Flags, and Catch Problems Early

Above all else, I think the most important concept that trumps every other suggestion in this article series is to be educated on elbow injuries and catch problems early. I have unfortunately been on the losing end of this battle as a younger coach. I have missed the early warning signs of overuse elbow injuries, and they escalated into painful injuries requiring months off of training. I think that most coaches and medical providers fall into the category of really just not knowing what signs to be concerned for, which is why I included this as the last piece in the article series.

Many times gymnasts will be stoic and not tell coaches about their injuries, or other times the elbow pain is written off as “part of gymnastics”. That is a big part of this, educated gymnasts that they should trust coaches and speak up about issues, as trying to tough it out through training can lead to much bigger issues down the road. When caught early as a Grade I or Grade II problem that only has bone flattening and no floating broken fragments, appropriate training modifications can have a chance to heal. More severe Grade III or IV OCD injuries that involve the cartilage, pieces of bone being stuck in the joint, and tissue break, unfortunately, do not have great success rates without surgery. This is which is where 6-8 month timelines for recovery come into play.

For me, any elbow issue that negatively impacts practice and lasts more than 3 training days is a cause for concern. If an issue continues despite resting and impact modification, it needs to be formally cleared by the appropriate medical provider through examination or proper xray, MRI, or CT imaging. That being said, it’s important that coaches and medical providers know the red flags when working with gymnasts.

Some recent studies (read more here and here) suggest 11-14 years old athletes tends to be the most common age for issues to start popping up. As I talked about in Part 1, this can often be a “Development – Talent Crossroad” point where gymnasts are in a rapid phase of development and also moving up quickly in levels.

This research paper reviewed and analyzed various studies on OCD, and outlined some common issues to look out for to catch big problems early. These include

- Ongoing pain or stiffness on the outside or front of the elbow when moving it

- Pain after lots of activity (weight bearing skills like beam handsprings, vaulting, lots of casting skill on bars, male pommels/pbar training, etc)

- Any kind of clicking, popping, cracking, or feelings of the elbow getting “stuck” when trying to bend or straighten the elbow

- Ongoing or progressing stiffness in the elbow joint, or inability to fully straight/bent the elbow compared to the other side

- Pain or buckling with weight bearing activities during daily life, or gymnastics

Concluding Thoughts

There are many more concepts to consider, but these are just a few of my biggest thoughts. My hope is that by sharing them in a blog, people will be exposed to them on a much larger scale. That way, not only can people understand more about these injuries, it may also spark new ideas to be investigated. This way, we can move towards preventing these injuries from spiraling into larger problems and help gymnasts have longer, more successful, and healthier careers. Best of luck, and thanks for reading!

– Dave Tilley DPT, SCS