Follow Up To Gymnast with Shoulder Instability and Pain During Overshoots, Plus Shoulder Performance Drills

A few months ago I posted an article related to general hypermobility/instability causing shoulder pain in one of my level 9 gymnasts. I brought up some concepts that I think are very important related to flexibility training, dynamic stability, motor control, and the importance of technique in training. I’m happy to say that she is pain free for her shoulder and has been back at full training/competing for a little over a month.

In the end it was 2-3 weeks of modified training not doing heavy swinging volume on bars. In place of these 5-6 hours per week that she would have been swinging, she did lots of technical bar drill work for the skills that were problematic (overshoots, cast handstands/pirouettes), did a supplementary shoulder stability program I gave her, and put some attention to other events. I wanted to do a quick follow up post in an effort to hopefully help prevent similar problems for other gymnasts.

Before I offer readers all the steps and exercises, remember you can learn all about my thoughts on shoulder pain in gymnastics, as well as how to help improve it, in the Medical chapter of my free online Ebook. Download that chapter here,

The Gymnastics

Recovery Guide

- Learn why sleep, time, nutrition, hydration, soft tissue care, and managing stress is essential to high performance and health

- Get specific tips on how to enhance recovery in gymnastics

- Understand the science behind recovery practices for developing athletes

We take our privacy seriously and will never share your information. Click here to read our full privacy policy.

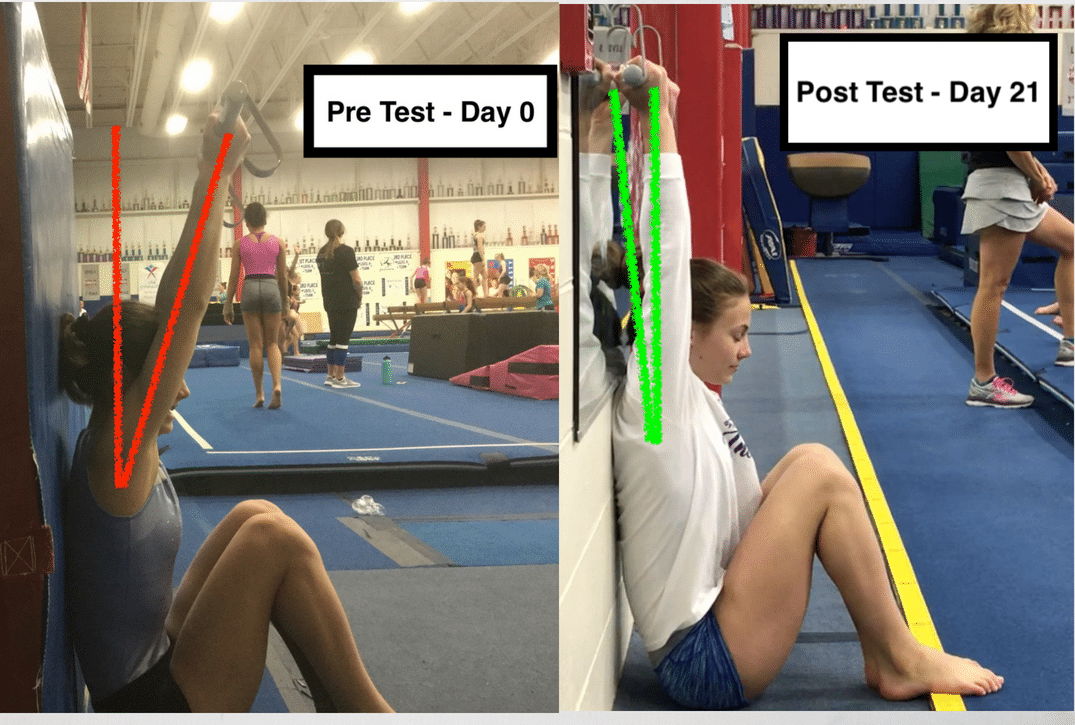

Correcting Her Overshoot

Here is a video of her overshoot handstand 1 week before she told me she was starting to get shoulder pain, taken sometime in mid December. Pretty much all of her overshoots were like this, and she told me the next week on bars these types of overshoots were what first made her left shoulder hurt when catching the low bar.

These are just my coaching thoughts but as you can see, she doesn’t really have the greatest scooping angle in her swing, which causes her angle of release to come out too early. Due to this, she generates quite a bit of speed traveling horizontally over the bar, rather than vertically scooping to the ceiling setting up the ideal handstand shape. This situation leads to a forceful pulling of her arms overhead when she catches the low bar, which makes her unable to find a good handstand to absorb the force.

This leads to the second point that her overhead shoulder tension is lacking, so when she hits the low bar she’s loose and her shoulders are forced back fast without control. With her underlying lack of static stability, I think this is where her shoulder was being subject to instability and tissue microtrauma. Lastly, you can see that she is lacking the ability to stay hollow and turn over as one piece from toes, to hips, to shoulders, to head. She lets her top hip open up early, she opens her chest as she travels in the air, and her head comes out which create an open arch shape versus maintaining a good controlled hollow. I think this also further contributed to the force being overloaded at her shoulder, versus through her core and thoracic spine.

We spent a lot of time looking at all these technical errors in Coaches Eye over a few weeks, then gave her some progressional shaping and drill work to do while her shoulder calmed down. We talked a lot about release angle, hollow turning as one piece, keeping good head alignment to not create and arch, and making sure she had a really strong overhead position when catching. Once she was clear of pain and showed better movement patterns, we started to build a new pattern for the skill. This is a video from a a few weeks ago that shows what I think to be a much better overshoot. More importantly, using this technique has caused the last 4 weeks of overshoots to be completely pain free which in my eyes is the bigger deal.

Why This Matters

I think this part to the training and injury prevention side of things can’t be stressed enough. Gymnasts who show problems with technique or who are missing the concepts of applying basics to high level skills may be at risk for something creeping up on them related to overload injuries. For a gymnast returning back to gymnastics following an injury, time has to be taken to correct the skill that originally caused the problem. If this isn’t done, were in trouble. By resting an injury and letting things heal, but not correcting the skills that caused it, were pulling the batteries out of a smoke a alarm but not putting out the fire. Traumatic accidents or falls are clearly in a different category. This is more for overuse type injuries, which are an epidemic in gymnastics. If it isn’t a quality issue of how they are doing the skill, we then need to look at quantity based measures like exposure rate, training programs, and their recovery to attack the issue. I hope this is an important thing readers can take with them to practice, because I personally feel it’s a huge cornerstone to how we can make a dent in overuse injury rates.

Dynamic Stability Drills

Here are a few of my favorite drills that I have put in during training to proactively work on dynamic control. These are examples of a few general motor control drills I have found useful, but there was much more to this gymnast’s program that was individually created to suit her movement problems.

Quadriped “T’ and “Y’s (Thanks to Dr. Aaron Swanson for this one, I’m a big fan of it): This drill is great to build a more traditional scapular control drill into a more challenging position. I don’t use a ton of isolated ” muscle strengthening” drills, but this version of these drills I have found helpful to change movement patterns. Having the gymnast go on hands and knees forces the shoulder lifting off the floor to work during open chain movement, while the opposite shoulder simultaneously has to stabilize with closed chain weight bearing fashion. I’m also a fan of this because it integrates the shoulders working into the core, and challenges a anti-rotation component to the core. A further progression of this could be to curl the toes under and lift the knees off 2 inches from the floor.

Piked Handstand “Shrugs”: A big problem I see with a lot of gymnasts is that they don’t have good dynamic scapular control overhead against their own body weight in moving/impact positions. Many have it statically in basic hand stands or drills, but fall apart during high speed and complex movement situations like overshoots. The very mobile gymnast needs pristine scapular control in order to help put the shoulder in a good position to disperse force. This drill helps to re-educate and train the gymnast to get their scapula and entire overhead complex into a better position. I think many coaches and gymnasts are already familiar with this, but being able to remind the gymnast of this pattern and build it into skill work is worth re-stating. This can be progressed to handstand bounces, shoulder taps, one armed handstands, and so on.

SLOW Bear Crawls: The Bear Crawl is by far one of my favorite motor control exercises to use. It’s purposefully done very slowly, so that the gymnast can be further challenged in fine tuned control. Many gymnasts I have worked with live in a constant high threshold state, and when put into a slow movement situation requiring fine tuned control they fall apart. Remember, knowing how to turn muscles off and fine tune movement is just as important as being able to turn them on and produce power. There are a hundred variations and progressions of a bear crawl like different directions, uphill/downhill, weighted, and so on. I personally think planked reverse bear crawls are one of the best variations to develop shoulder and scapular control for overhead movements. It promotes weight bearing scapular stability and also involves the natural movement of the scapula and shoulder complex during overhead movements. Here is the basic version a gymnast should master first, then a few progressions past this to try.

Turkish Get Up: This certainly isn’t a new one, as I have written about the Turkish Get Up many times before. I’m a big fan of it and I use it very often as a bar side station during blind/pirouette work outs. For the athlete with lots of overhead mobility, this is a great drill to force the entire overhead arm chain to reflexively react to a changing base of support. If your interested in learning more about the TGU, check out this more extensive article I co-authored with my good friend Dave Picardy, who is a fantastic Olympic Lifting/Strength coach and also the owner of TreeHouse Training here in the North Shore of Boston. Here are two video examples.

These two examples aren’t flawless and have some more work to be done. This is a complex drill, so I would seek out someone who knows the proper steps to teaching it before you put weight in someones hand to load them.

Concluding Thoughts

Important Note: In this scenario, because of my medical background I was able to make decisions about a shoulder program for the gymnast who was having pain. Coaches or gymnasts who are reading this shouldn’t be “treating” problems related to pain with these type of programs. The best thing to do is to have the athlete see a healthcare provider and get a movement assessment, as there are many possible reasons they could be in pain. After being assessed, the entire team helping the gymnast can then work in conjunction together to formulate the best plan. With that said, I think this can serve as a post coaches and gymnasts can use for staying ahead of issues while enhancing skill performance. If there are clinical people reading this who treat gymnasts, hopefully it helps bridge some training concepts to the clinic. For now, I hope this has been helpful!

– Dr. Dave

References

- Andrews, J., Reinold, M., Wilk, K. The ATHLETE

’s Shoulder. Second EDITION

’s Shoulder. Second EDITION , 2009

, 2009 - Wilk KE, Macrina LC, Reinold MM. Nonoperative rehabilitation for traumatic and atraumatic glenohumeral instability. North Am J Sports Phys Ther 1(1):16-31, 2006.

- Wilk KE, Arrigo CA, Andrews JR. Current concepts: The stabilizing structures of the glenohumeral joint. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 25(6):364-79, 1997.

- Wilk KE, Andrews JR, Arrigo CA. The physical examination of the glenohumeral joint: Emphasis on the stabilizing structures. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 25:380-9, 1997.

- Cordasco FA. Understanding multidirectional instability of the shoulder. J Athl Training 35(3):278-285, 2000.

- Reinold M., Wilk K: Treatment Of The Shoulder: Principles of Dynamic Stabilization DVD

- Manske R., et al. Current Concepts In Shoulder Examination of The Overhead Athlete. IJSPT Oct 2013; 8(5): 554 – 578

- Andrews, J., Reinold, M., Wilk, K. Current Concepts in the Evaluation and Treatment of the ShoulderinOverhead

Throwing ATHLETES

, Part 2: Injury Prevention and Treatment. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach 2(2) 2010

, Part 2: Injury Prevention and Treatment. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach 2(2) 2010 - Reinold, M. Cressey, E. Functional Stability Training for the Upper Body; 2014

- Myers JB, Lephart SM. The role of the sensorimotor system in the athletic shoulder. J Athl Train 35(3):351-363, 2000.

- Paine, R., Voight, M. The Role of The Scapula. IJSPT: 8(5): 617 – 629; 2013Caine D., et al. The Handbook of Sports Medicine In Gymnastics. First Edition. John Wiley and Sons, 2013Cook G., et al. Movement – Functional Movement Systems: Screening, Assessment, Corrective Strategies. First Edition. On Target Publications, 2010.

- Cynthia H.w., Magnusson P., Increasing Muscle Extensibility: A Matter of Increasing Length or Modifying Sensation? PHYS THER. 2010; 90:438-449.

- Weingroff, C. The Stretching Code: Audio lecture broadcast. www.MovementLectures.com

- Ben M, Harvey LA. Regular stretch does not increase muscle extensibility: A randomized controlled trial. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(1):136-144.doi

: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00926.x.

- Hargrove, T. A Guide To Better Movement. The Science and Practice of Moving Better With More Skill and Less Pain; 2013