How Much Flexibility Is Too Much For A Gymnast?

I’ve been touching on this concept a lot in the last year, and I think it’s very important for the people involved in gymnastics to consider. Gymnastics is well known as a sport that requires an excessive amount of mobility and flexibility (I used flexibility in the title as the gymnastics world recognizes this, but flexibility and mobility are completely different).

However, there is a very fine line between a gymnast having enough motion for skills and having too much motion that is uncontrolled, creating increased injury risk with a decrease in performance. Gaining excessive motion for gymnastics skills comes with the crucial need for the gymnast to learn how to control it, as the forces of gymnastics are enormous. A gymnast needs good alignment with proper strength/stability that helps support joints. This assists in dispersing the forces of gymnastics across multiple joints, preventing overload or problems at any one spot.

Although mobility and flexibility is a mainstay of gymnastics training, I feel many gymnasts shouldn’t be looking to gain more motion. Many gymnasts are born naturally hypermobile but then continue to gain more range through gymnastics that can lead to elevated injury risk, instability, or pain quickly. I think instead these gymnasts are better served training dynamic stability and learning how to control the excessive motion they already have. I wanted to illustrate this point by talking about a gymnast whose excessive motion and lack of dynamic control lead to shoulder instability and some recurring pain during bars.

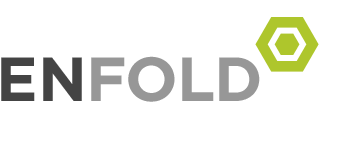

This gymnast joined our team earlier this year, and after watching her skills over a couple weeks I could already tell she was inherently very mobile. She is very talented and has some good skills, but it did seem like her huge amount of mobility was making it tough to control some of them. She brought up to me that she has had intermittent shoulder pain with a variety of different skills like swinging giants, free hips, and sometimes catching overshoot handstands. Having seen a few gymnasts with this type of problem escalate quickly, I wanted to jump on it early. I took some time to look at her shoulder during practice one night and sure enough found she had an insane amount of shoulder mobility. This was the case for both of her shoulders, but more on her left which was the painful side. Here are a few pictures I took from the whole process.

As you can see, it’s pretty crazy how much motion she has (borderline creepy). You should have seen her face when I showed her the pictures. When I tested out the passive motion of her shoulder joint and capsule, it was incredibly mobile to the point where I felt her shoulder sliding too much in all directions. She had a Beighton’s Score was a 7/9, which is just a scale to measure laxity. Along with this she has an extremely mobile upper/ lower spine, hips, and some problems for shoulder blade stability.

As a side note she also has a tendency to hang out like this waiting in line for bars, which I stay on her about not doing anymore.

Why This Matters For Gymnastics Training, Injury Risk , and Performance

A very important point for readers is that despite being so mobile, in the last few years she unfortunately continued to work flexibility and push herself/get pushed on till she “felt it” during stretching. Don’t get me wrong, as a coach/former gymnast I completely know and understand that we need a large range of motion in gymnastics both for skill performance and aesthetics.

But like I said, controlling that motion and keeping it in check are vital for a gymnasts. In her case, aggressive stretching was the last thing she needed to be doing. Her excessive uncontrolled motion with her shoulder sliding around during bars has likely been creating microtrauma to structures of her shoulder and her brains expression of pain due to threat. Ideally good neuromuscular control would help keep the joint to be in a proper position during movement (a concept known as “centration”).

The rotator cuff muscles have a primary function of doing this by working to centrate the head of the humerus and maintain the alignment during movement. This works in conjunction with a variety of other supporting structures to help stabilizer the shoulder under changing conditions.

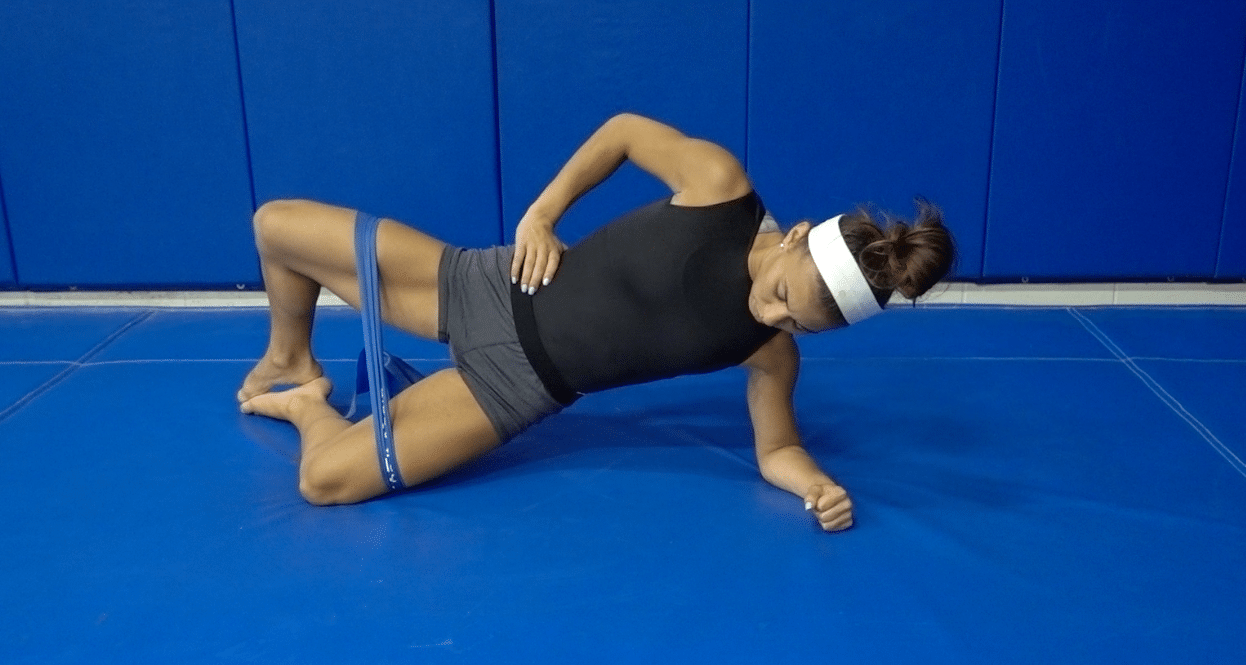

Keeping things properly aligned with proper dynamic stability during high force times like bars would help to prevent the microtrauma/pain. These concepts are why I feel for gymnasts like her, not stretching more and shifting focuses to learning to control motion may be the better route. This is also why I’m such a big advocate of regularly working dynamic shoulder stabilization drills during pre-hab/strength for our girls who have the mobility and can perform it properly.

I want to build up this dynamic stability and assist with teaching proper control under load/fatigue through things like Turskish Get Ups, Famers/Suitcase/Overhead carries, Crawling Variations, Reactive Neuromuscular Exercises, Traction Control Drills, and more.

Along with this inherent hyper mobility she had a huge difference in how far I could put her shoulder and how much she could move it herself against gravity with good control. When I tested her under dynamic conditions things continued to fall apart. Further support to why controlling skills was showing up, affecting her performance. She has a combination of some missing strength, but more importantly a lack of proper motor control/dynamic stability.

Having too much motion and instability can can lead to problems noted above, but it can also be dangerous for someone to be at risk for subluxation or dislocation. Recurrent shoulder/spine/elbow/hip instability can be a huge issue in gymnastics. On the same lines this large range of uncontrolled motion can also sometimes cause the nervous system to backfire due to the threat perception, and lock down areas to create stability. I have an opinion that many “tight” gymnasts may continue to fight an uphill battle working mobility when they really have dynamic instability issues as the root cause. This leads to frustration with coaches and gymnasts, but also a huge plateau in gymnastics performance with increasing injury risk.

This same concept also creates decreased gymnastics performance as power and force can not properly be created/absorbed from unstable structures. Creating stability throughout the body and being able to transfer force is a hallmark of successful gymnastics. Unstable shoulders, spines, and hips are a number one way to create “energy leaks” as Stuart McGill calls it to decrease power output. To increase power output and the bodies ability to accept/disperse force properly we need to train it to be optimally aligned with good strength and control under changing conditions. I think many readers are familiar with this, seeing very hypermobile gymnasts who struggle to “stay tight” and as a result leak out power during tumbling, vaulting, swinging bars, and so on.

I try to separate my gymnast into those that need more mobility work, and those who are better served with dynamic stability and control work. Certainly some gymnasts do need mobility work, but I would encourage people to first find out why they are tight then pursue correcting the true cause. Then, you can follow up appropriately with what needs to be done. I feel many gymnasts with plenty of motion are better served to maintain that motion and then focusing on how to control it with additional drills. Each gymnast is an individual with their own distinct movement profile, and I feel that it’s very important to take into account individual movement profiles for training just like we do with gymnastics skill development.

Concluding Thoughts

The take away I wanted to offer readers from this post is that I feel not every gymnast needs more flexibility work or getting pushed on for stretching. I think we quickly cross the line into dangerous territory of instability and micro trauma with such high force of gymnastics. Just because someone has plenty of motion during over splits or shoulder stretching doesn’t mean it automatically transfers over to skill work. I don’t encourage my hypermobile gymnasts to show off their Gumby like properties or keep cranking on mobility. As a parallel to this as a coach I don’t want to just keep pushing to see how far I can get them. Just because the gymnast has lots of motion certainly doesn’t mean they know how to safely access it or control it under load during gymnastics skills. Anytime you work gaining mobility with a gymnast, you have to make sure that you are following it or regularly working dynamic control/strength in that new range. This concept goes hand in hand with using proper skill progressions, technique, and practicing skills to understand control. Both parts are equally as important for training.

Due to this gymnast’s natural laxity and her displaying excessive motion with poor control I made the suggestion to temporarily reduce her bar volume while the pain revolves and replace that time with a dynamic stability program to do every day. When we do mobility work I have this gymnast work to maintain full range she needs for gymnastics skills, but not crank on herself into crazy ranges. So far so good with her case, but I’ll keep some updates as we move through season. For this gymnast it happened to be a painful shoulder, but I have seen very similar examples of excessive mobility causing problems in other areas of hips, lower backs, knees, and elbows. I think understanding some of these ideas is really important for the gymnastics world to always have in mind during training. That’s all for now, hope it was helpful.

Dave

References

- Andrews, J., Reinold, M., Wilk, K. The ATHLETE

’s Shoulder. Second EDITION

’s Shoulder. Second EDITION , 2009

, 2009 - Wilk KE, Macrina LC, Reinold MM. Nonoperative rehabilitation for traumatic and atraumatic glenohumeral instability. North Am J Sports Phys Ther 1(1):16-31, 2006.

- Wilk KE, Arrigo CA, Andrews JR. Current concepts: The stabilizing structures of the glenohumeral joint. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 25(6):364-79, 1997.

- Wilk KE, Andrews JR, Arrigo CA. The physical examination of the glenohumeral joint: Emphasis on the stabilizing structures. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 25:380-9, 1997.

- Cordasco FA. Understanding multidirectional instability of the shoulder. J Athl Training 35(3):278-285, 2000.

- Reinold M., Wilk K: Treatment Of The Shoulder: Principles of Dynamic Stabilization DVD

- Manske R., et al. Current Concepts In Shoulder Examination of The Overhead Athlete. IJSPT Oct 2013; 8(5): 554 – 578

- Andrews, J., Reinold, M., Wilk, K. Current Concepts in the Evaluation and Treatment of the Shoulder inOverhead Throwing ATHLETES

, Part 2: Injury Prevention and Treatment. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach 2(2) 2010

, Part 2: Injury Prevention and Treatment. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach 2(2) 2010 - Reinold, M. Cressey, E. Functional Stability Training for the Upper Body; 2014

- Myers JB, Lephart SM. The role of the sensorimotor system in the athletic shoulder. J Athl Train 35(3):351-363, 2000.

- Paine, R., Voight, M. The Role of The Scapula. IJSPT: 8(5): 617 – 629; 2013Caine D., et al. The Handbook of Sports Medicine In Gymnastics. First Edition. John Wiley and Sons, 2013Cook G., et al. Movement – Functional Movement Systems: Screening, Assessment, Corrective Strategies. First Edition. On Target Publications, 2010.

- Cynthia H.w., Magnusson P., Increasing Muscle Extensibility: A Matter of Increasing Length or Modifying Sensation? PHYS THER. 2010; 90:438-449.

- Weingroff, C. The Stretching Code: Audio lecture broadcast. www.MovementLectures.com

- Ben M, Harvey LA. Regular stretch does not increase muscle extensibility: A randomized controlled trial. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(1):136-144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00926.x.

- Hargrove, T. A Guide To Better Movement. The Science and Practice of Moving Better With More Skill and Less Pain; 2013