Gymnastics, Please Stop Doing These Stretches (Part 2)

In the first part of this article, I went over why pushing hip hyperextension and back leg split flexibility stretching makes me really concerned. In this article, I want to go over two types of commonly used passive shoulder stretches I fear are contributing to the high rates of shoulder injuries and instability in gymnastics. I treat 3 times as many gymnasts for shoulder instability and injury than hip problems. It’s always a shame to hear that part of their injury comes from a lack of scientific rationale for their shoulder stretching routines.

Remember you can download all my thoughts on gymnastics shoulder flexibility, along with the exact exercises and drills I give gymnasts, for free in this PDF, “10 Minute Gymnastics Flexibility Circuits”

Download My New Free

10 Minute Gymnastics Flexibility Circuits

- 4 full hip and shoulder circuits in PDF

- Front splits, straddle splits, handstands and pommel horse/parallel bar flexibility

- Downloadable checklists to use at practice

- Exercise videos for every drill included

Again, I want to point out I am not “attacking” the coaches, athletes, or medical providers. This is post is more intended to address some principles used in gymnastics flexibility programs, in an effort to help athletes increase performance and reduce their shoulder injury risk over a longer career.

The first stretch that concerns me is pushing skin the cat or hyper extension type stretches, and the second is pushing improperly set up hyper flexion / overhead stretches.

In my eyes, the first picture below is complete insanity, and I feel has no benefit at all. Coaches doing this without understanding the anatomy seriously need to take a step back and rethink their rationale for using it. The second picture of an extreme “skin the cat” type stretch is also something I feel we need to move away from.

The last stretch worth mentioning are pushing the shoulders of athletes while in a hands elevated/internally rotated position. I will add the caveat that this stretch could be possibly be used to mobilize the upper back / thoracic spine, if it has been ruled in as a problem through a movement assessment. Most people are not taking that path, however, and are using it to mobilize the shoulder joints. I will explain more below as to why I am not a huge fan of this approach.

Table of Contents

Why The Concern?

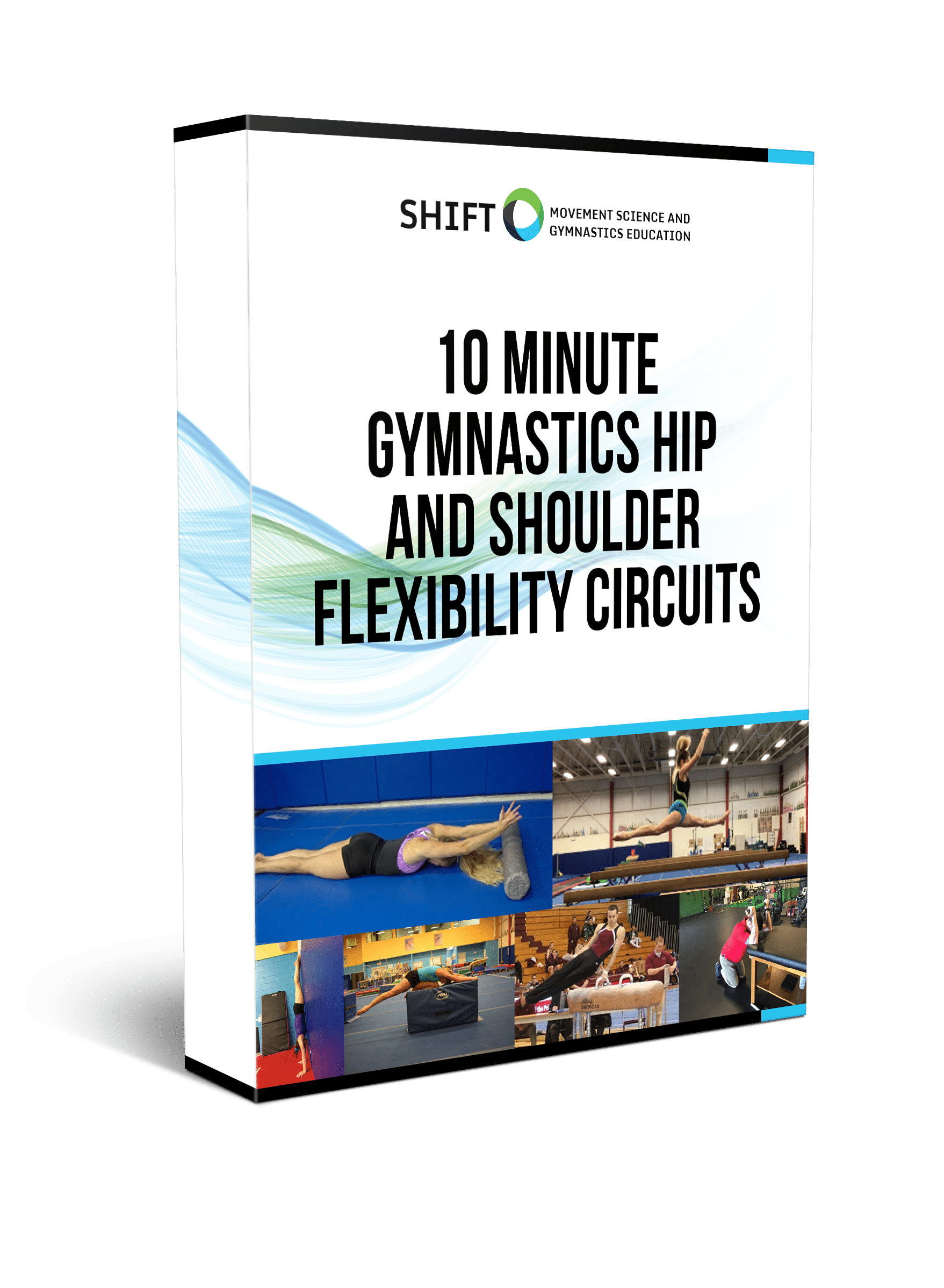

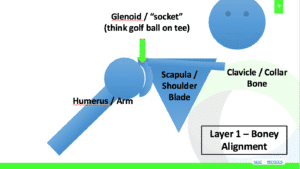

In the first article, I outlined the concept of passive (ligaments/joint capsules) and active stabilizers (more muscular based) of the hip. The same concept holds true for the shoulder, but is even more important as the shoulder has much less inherent stability.

Passive structures like the glenohumeral ligaments, labral tissue, and boney configuration are things out of a gymnasts control that help contribute to stability during high force gymnastics skills. Naturally mobile gymnasts have lacking static stability, and as a result depend on extremely developed strength/dynamic stability to prevent the shoulder joint from subluxing during gymnastics skills.

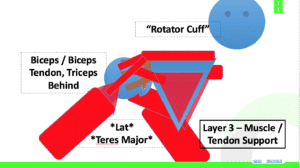

In relation to skin the cat stretching, the excessive range of motion of the gymnast’s shoulders into this hyper extended motion just tends to just create excessive anterior humeral head migration. This puts a ton of stress on the ligaments/capsule in the front and underside of the shoulder. Not to mention, it can also strain the biceps tendon and other sensitive soft tissue structures of the shoulder.

People tend to use the stretch or the hands behind the head “angel wing” type stretch to mobilize the pec tissue. Given the anatomical set up of the pec major/minor I think we really are getting minimal soft tissue involvement and instead are putting way more pressure on the anterior ligamentous, capsular, and tendons.

With the shoulder joint placed into extreme ranges of overhead elevation (especially when someone blocks and pushes the back of the shoulder joint) a lot of stress is placed on the inferior glenohumeral ligaments creating humeral head subluxation. Typically the goal of these types of stretches is to work the latissimus tissue.

However when someone sets up a typical shoulder stretch with a hyper extended spine and internally rotated shoulder position (last picture above with hands on block), the intended latissimus tissue likely is not experiencing any tension. These passive structures that taking the stress should not be getting stretched out more, especially in a naturally hyper mobile individual that has inherent ligamentous laxity. This high risk impingement position can also stress rotator cuff tendons.

I feel due to these stretching methods and a lack of attention to developing strength/dynamic stability, many gymnasts experience instability based pain with high force traction swinging and bar based skills over time. When these gymnasts come to me in the clinic for treatment, with range of motion or other testing I can sublux their humeral head out of the socket due to their lacking stability. Remember, gymnasts need exceptional stability to tolerate release and one arm bar skills.

Another common mechanism for gymnasts starting to get pain with beam series or tumbling as they hit their backhandspring or Yurchenko angle in a slight broken shoulder angle and their lax/unstable shoulder subluxes posterior and inferior in the glenoid. I think the areas of the capsule/joint that get stretched with the above-noted stretches set these gymnasts up for this over time. Here is a video I made last year showing this (aware of the hand placement issue).

What really drives me nuts is that during these stretches coaches, the athlete, or a partner gymnasts are misinterpreting “pain” of muscle stretch with joint and tendon or joint irritation. When I teach these concepts in seminars many gymnasts report anterior biceps pain or rotator cuff referral pain, which should not be the case. Every gymnast should be asked “where do you feel this” and if they point to their shoulder joint line or biceps tendon area they need to stop.

Again, I encourage people to look into more education if they want to learn more. Here are a few great resources.

-

Wilk K., Macrina L. Nonoperative and postoperative rehabilitation for glenohumeral instability. Clin Sports Med. 2013 Oct;32(4):865-914. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2013.07.017.

Caplan, Julien, Michelson, Neviaser. Multidirectional Instability of the Shoulder in Elite Female Gymnasts. American Journal of Orthopedics.

Reinold, Gill, Wilk, Andrews. Current Concepts in the Evaluation and Treatment of the Shoulder in Overhead Throwing Athletes, Part 2. Sports Health.2010 Mar; 2(2): 101–115.

Generalized joint laxity and multidirectional instability of the shoulder. Joints. 2013 Oct-Dec; 1(4): 171–179.

Warth, Ryan J, Millett, Peter. Physical Examination of The Shoulder: An Evidenced Based Approach. 2015

Wilk, Andrews, Arrigo. The physical examination of the glenohumeral joint: emphasis on the stabilizing structures. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1997 Jun;25(6):380-9

What To Do Instead?

The first thing to do is truly make sure that what you are dealing with in terms of the gymnasts “unflexible shoulders” is actually a shoulder muscle / soft tissue problem. There are many other things that can limit a gymnast’s arms to go overhead. This can range from poor pelvic or core control, to thoracic mobility restrictions, to lacking scapular strength/control, or even weight bearing wrist extension limitations. These things must all be screened for. It’s also important that clinicians assess capsular motion to better understand what’s going on. For coaches, I suggest you just stick to non hands on based assessments.

For those gymnasts with true lat or teres major soft tissue restrictions, my first suggestion would be to try some light manual or self soft tissue work with a lacrosse ball/foam roller. I would then follow this up with a proper lat stretch using a floor bar and deep breathing. I go into the floor bar concept below in a video I shot a few months back. I feel with the use of floor bars, blocks, and beams this can easily be implemented in a large group setting. I feel these target the correct anatomy are much more effective with less risk of shoulder joint and rotator cuff irritation.

For these following two pec minor and pec major stretches, make sure that proper set up and core engagement is used. The gymnast should only feel a stretch in the front of their chest, they should feel no shoulder pain. I personally feel these are more effective and safer for the shoulder joint compared to typical skin the cat type stretches.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PYMao0YWzkc

If a gymnast does show limitations in their thoracic mobility, I would suggest some properly set up thoracic mobility drills with diaphragmatic breathing (one above in video and one below), and then I would then follow it up with some version of a wall angel to build the new thoracic motion into overhead reaching needed in skills.

I also commonly find that gymnasts appear to have lacking overhead mobility in skills, but then in unloaded positions show excessive passive ranges. I feel strongly that these gymnasts do not need to be stretched more and that instead, they learn how to control and strengthen the ranges they show passively. I think this is what makes their active ranges “stick” neurologically and show up in gymnastics skills like handstands, tumbling, and so on. Like I noted with the hip article, I separate my gymnasts into those that need more mobility and those that need more control. For those in the second category with natural laxity, try to work some of these control drills instead.

There are plenty more important drills like

- 90/90 ER or ER and presses

- quadruped T’s an Y’s

- 1/2 kneeling presses

- hanging scapular circles

- slow bear crawling/plank sliding

I try to add a few of these into strength regularly. I think these are extremely important for many gymnasts to be doing to protect their shoulders through rotator cuff strength and other dynamic stability drills.

And finally, you can also put these in a complex if you’re looking for a practical way to implement it in practice.

What About Male Gymnasts?

This inevitably comes up whenever I talk about this subject, and rightfully so. Compared to males, female coaches and athletes have to remember men inherently have more upper body development and from a younger age have much more skill work on the upper body (4 events vs 1 on females). I do agree that male gymnasts require working mobility/strength into hyper extension due to many of their skills requiring it. Tons of pommel work, muscle ups, transition strength like Azarians, inlocates/dislocates, dip cuts/dip swing/front uprises on p-bars, and high frequency in bars/jams/eagles all require strength/stability in this extreme range of motion. The list could go on way past this, and due to these skills being used all the time on multiple events I do feel it should be prioritized in male gymnastics.

With that said, the first and most important part is I think male gymnasts should have the underlying movement pre-requisites against gravity alone before they load any extreme ring, pbars, or dip motions. This is especially true in our youth athletes. A lot of time must be spent on proper motor control and strength through the entire range.

This also holds true for females who are looking to get more into doing dips/rings for their training (thinking CrossFit). It’s great they want to do it, but they need a lot of prep work to stay safe. Here are a bunch of drills, with some of my favorites from the FRC system, that I feel should be staples in all men’s gymnastics programs (pending there is no pain or injury present).

I also think male gymnasts need a huge amount of focus on overall scapular strength, rotator cuff balance, and dynamic stability before we ever load them into stutz’s, diams, and loaded ring work. The shoulder is much more than just pull ups, rope climbs, push ups, and prime mover strength.

It also requires a huge amount of local stabilizer work and co – contraction work that must occur. Many great coaches already add in theraband and weighted shoulder prehab which is great. It needs to be balanced with progressive loading that promotes shoulder chain dynamic stability. I think things like turkish get ups, EZ mover crab sliders, and a slow progression into these skills is crucial.

Due to the amount of time and skill work in this area, I do think that dips should be part of men’s gymnastics strength routines. However, I think dips always need to be approached cautiously with good technique as a focus. Simply having a young gymnast hop up and bang out dips with terrible form only to fail around or get stuck at the bottom is dangerous. It’s comparable to not wanting someone to bottom out their jam or dislocate on rings. I strongly suggest people use partner spots, banded assistance, or other modifications of the dip to progressively build up the strength/stability/motor control.

So that’s all for part 2 on the shoulder side of things. As I noted in the hip article, shoulder stretching is not the issue here and we do it daily in our dynamic warm up. I also could see the argument for increasing thoracic mobility with some of the overhead block stretches, if that has been ruled in as an issue through a movement assessment.

The concern is more with pushing certain passive stretches without proper scientific rationale or a movement assessment in front of the intervention. For the safety of the athlete and their performance, we need to think critically about what were doing. I purposefully put these articles close in release, so people could have all the information they needed. Take care,

– Dave Tilley DPT, SCS