3 Ways to Reducing Knee and Ankle Injury Risk By Building Impact Volume in Preseason

It’s been a few months since I have put together some brand new blog content. I have been brainstorming on some ideas, and also found some useful concepts in the gym, so I wanted to get back into the swing of things with regularly published content.

Overuse knee and ankle injuries are by far one common issue that gymnasts, coaches, and their parents deal with. This is typically due to very high forces and high repetitions of impact volume (tumbling, landing dismounts, jumps, etc). This has been shown in quite a few research studies looking at the rates of injury in pre-collegiate, collegiate, and elite gymnasts (find that research here, here, and here).

Overuse knee injuries include Osgood Schlatters, stress reactions or stress fractures of the leg bones like shin splints, Sinding Larsen Johansson Syndrome, meniscus irritation, patellar tendinopathy, or cartilage issues like OCD.

Overuse ankle injuries typically come in the form of Sever’s disease, stress reactions of the ankle/foot bones, Achilles tendinopathy, Inslin’s disease, talar dome bone bruises (pinching pain gymnasts feel in the front of their ankle when landing), and also OCD lesions in the cartilage.

The research has outlined some general factors that can reduce the risk of these injuries such as pulling back on high impact training during times of rapid growth (research here and here), using proper jumping and landing mechanics (research here, here, and here), and having a really robust physical preparation / strength and conditioning programs (research here and here).

But, unfortunately, the rates of these injuries still continue to skyrocket causing gymnasts much pain/frustration, but also creating huge amounts of missed time from practice and competition. I have worked with some gymnasts who due to various injuries accumulate 1-2+ years of missed training and competing time.

Table of Contents

So What’s Causing So Many Injuries?

Despite some useful tools, the real issue behind so many overuse impact injuries is the one most people in gymnastics don’t want to admit: doing too much impact volume. Between warm-ups, skill training, drills, and physical preparation, it’s not uncommon to see gymnasts taking 1000’s of impact repetitions over the course of a week. That means possibly 10,000+ per season.

Interestingly enough here, I actually don’t think that impact volume is inherently ‘bad’ for a gymnast. There’s no causative research I’m aware of that says impact volume = overuse knee or ankle injury. I feel it’s more the impact volume a gymnast is not prepared for is what’s dangerous.

And this is where the real root of the issue starts to shake out. More often than not, during the summer or noncompetitive months, gymnasts are doing skills mostly to softer mats, the foam pit, or softer resi mat and Tumbl Trak type setups.

Club or JO gymnasts typically do this for 3 months, as well as college gymnasts who are home from school training. Also, there usually is more emphasis on strength training work during the summer, and not as much plyometric or impact work (which is a good thing to give their bodies a short break)

But, once the club gymnasts get back into the preseason, or college gymnasts get back to school in the fall, everyone starts to panic because routines need to be built as the competitive season is creeping up.

So what typically happens is coaches and gymnasts go from a relatively low volume and low intensity stimulus on the body (tumbling to foam, dismounts to soft, minimal plyometric conditioning), and ramp up like crazy in a short period of time to a high volume and high-intensity stimulus (more intense plyo warm ups, tumbling on floor, dismounts on hard, lots of plyometric conditioning)

This is usually where things start to go bad. The sudden rapid spike in plyometric impacts combined with more skill training on hard causes many young gymnasts to report pain in their knees, ankles, and lower back. They typically progress to flare-ups of the injuries noted like Sever’s disease, shin splints, patellar tendon issues, or if very bad stress fractures.

What Do We Do To Help?

Unfortunately, this is where most gymnasts live in a grey area. They continue to get flare-ups of these overuse injuries, medical providers tell them to stop, they stop for a few weeks and do low-level rehab work, but when they go back to practice the volume is high again, and their injury flares up.

It leads to a vicious cycle where gymnasts feel like medical providers don’t get it, coaches lose trust in medical providers and try to handle things on their own, and gymnasts snowball these injuries trying to live off Advil and ‘being tough’. It then catches up with them and they have to get put in a boot, take long periods of time off, or worse get surgery. This is where we need to take a harder look at workloads for impact volume, and balancing the amount of work to rest.

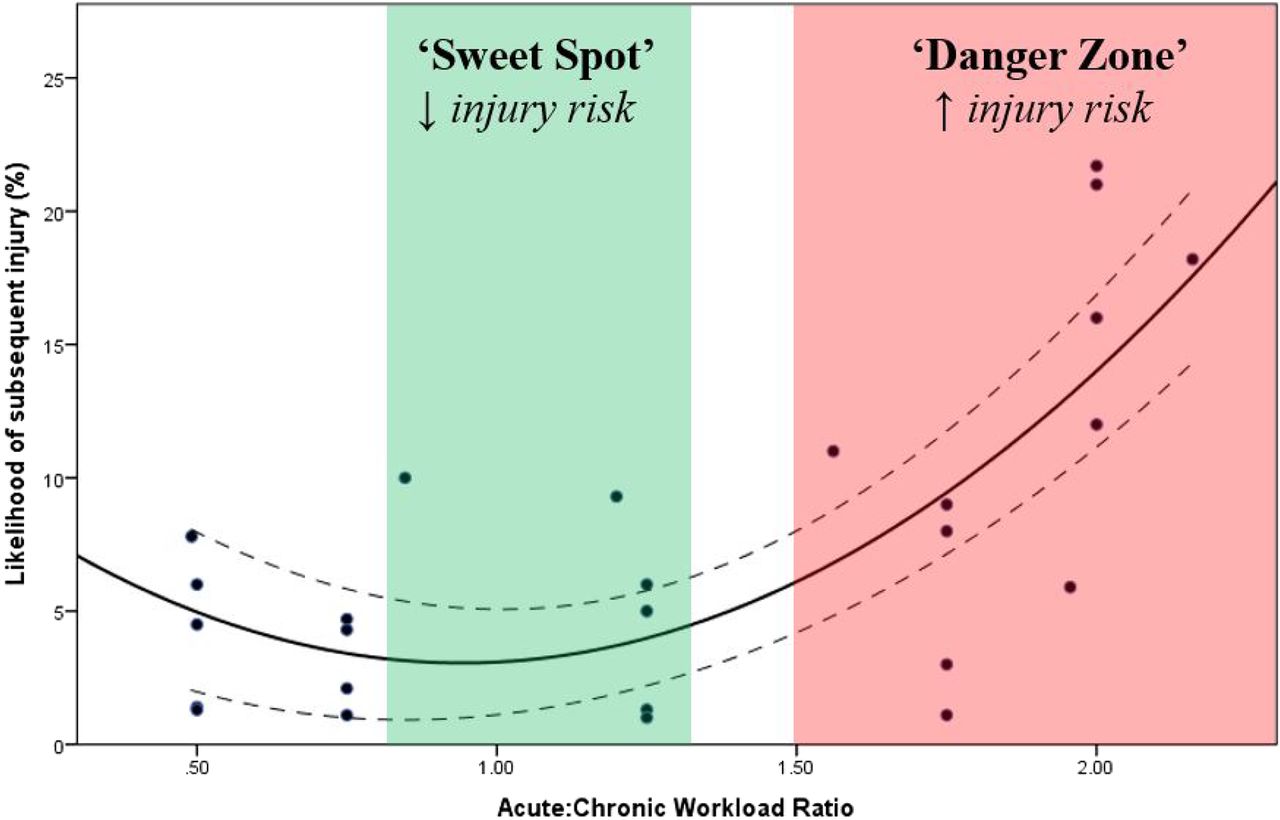

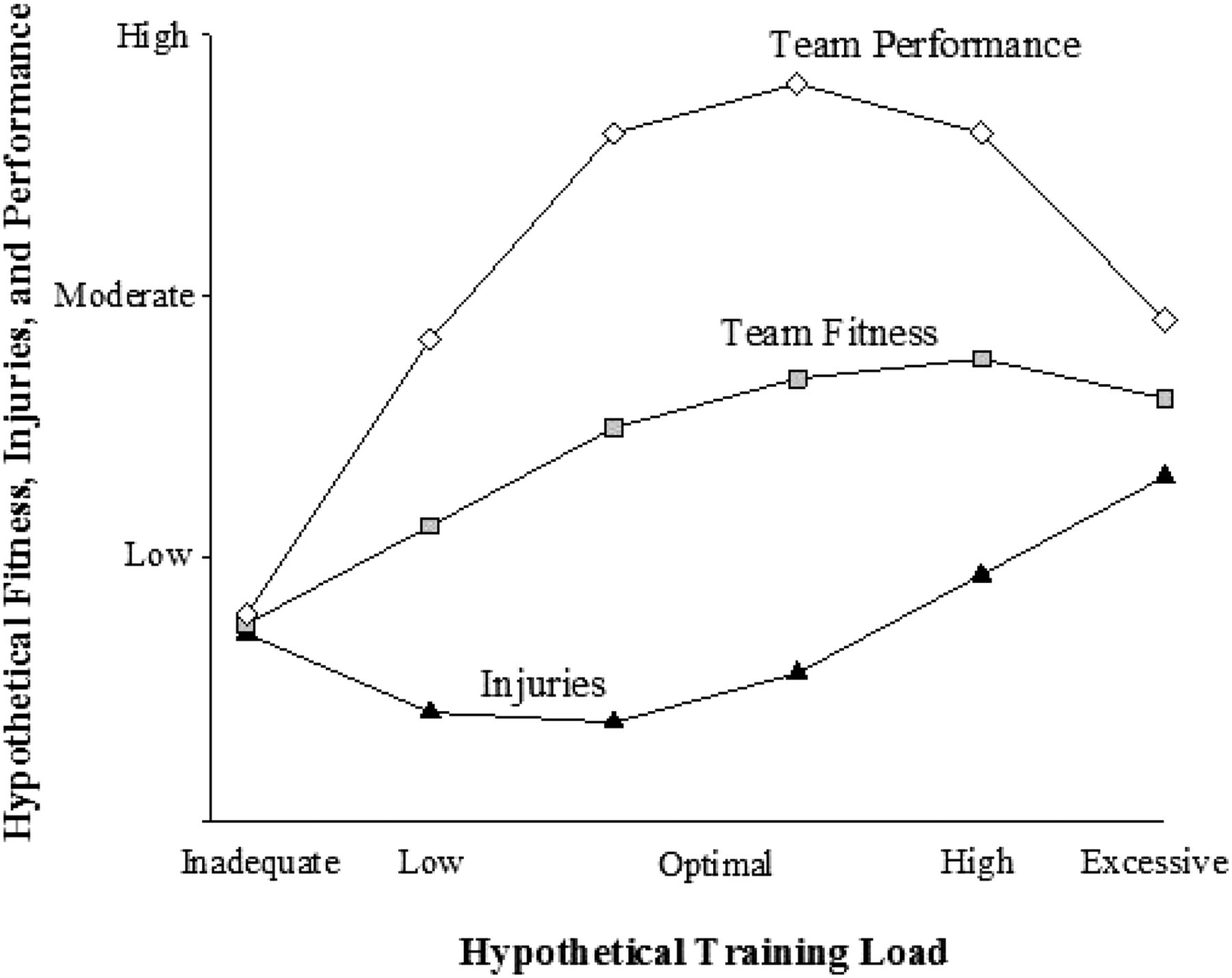

Some fantastic research from Tim Gabbett and others is what brought to light the concern for suddenly spiking impact volume, or more generally acute workload, due to elevated injury risk (research here and here). It’s for this reason that we don’t suddenly want to throw tons of new plyometric drills, lots of floor impacts, or tons of hard dismounts at a gymnast in one week. It spikes their ‘acute’ loaded without too much ramp up, and may create injury risk.

Source – https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/50/5/273

Interestingly enough though, Tim’s research has also demonstrated that slowly building to a high chronic workload (in this case lots of impacts over a 3-4 week span) may actually be protective against injury (research here and here). Simply put, if we slowly build up the impact volume using objective measures, allowing for proper amount of time between pushing hard and allowing recovery, we may be able to help reduce injury risk.

Source – https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/50/5/273

SO, rather than have 1000s of gymnasts just gritting their teeth with these painful issues, I wanted to offer 3 things that have really helped me based on this research and other strength and conditioning research available.

1. Build Impact Workload Slowly Over A Month

Probably the most important thing that we can do for young gymnasts is slowly and objectively build their impact volume up. This has to happen over a 3-6 week period starting way ahead of the preseason, and has to follow some sort of objective guideline.

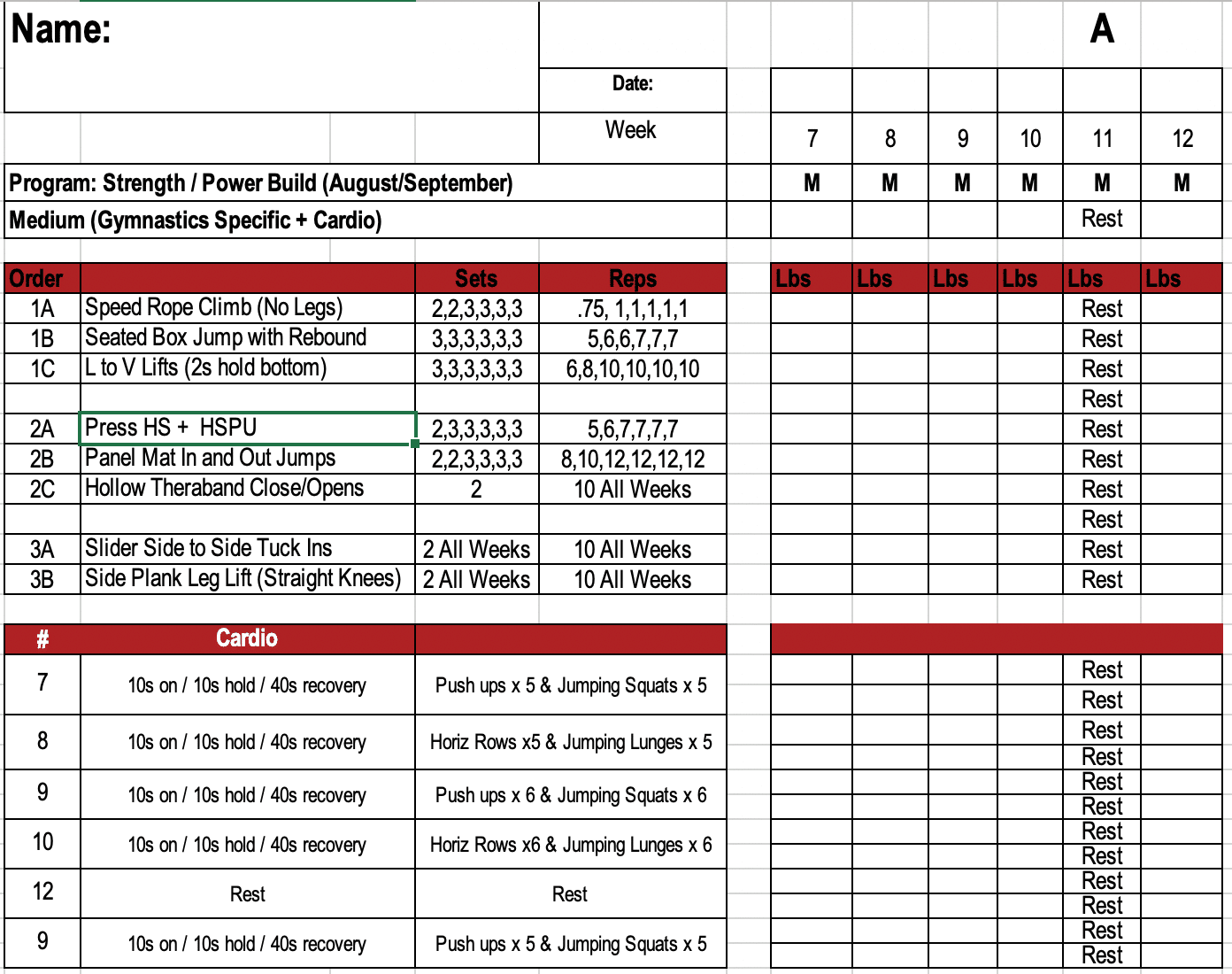

For me, one of the ways I really like doing this is through strength and conditioning. During August and September, we slowly build up the number of impacts on hard ground using depth jumps, pogo hops, seated dumbell jumps, and plate hops that are tracked in each gymnasts individual strength binder.

The other way I like to do this is having gymnasts do 3-5 basic tumbling passes on the real floor using a sting mat, rather than just tumbling all to stacked mats or soft for upgrades, during floor. The same goes for basic dismounts during a warm-up on bars. This allows gymnasts to add in 25-50 plyometric impacts during events, and over the course of the 6 weeks, we can continue to build more time on the hard floor.

If we think about it over 6 weeks, and not 6 days, we essentially allow for more time to move from the ‘floor to the ceiling’ as Tim Gabbet calls it, and prepare their body for the high impact loading in a safer way. Then things progress naturally doing dance throughs, then 1/2 routines, then full routines, and so on.

I personally try to objectively build impact volume over 6 weeks. Like I said, we slowly build volume up using exercises like depth jumps, plate hops, and pogo hops. You can see here how over 6 weeks we do this on one day of our program (seated jumps with rebound, in and out panel mats, jumping squats) slowly building volume, intensity, and total workload over 6 weeks. Other days have various plyometric drills, and this helps add total volume.

2. Avoid Sudden Spikes in Impact Volume

Along with what was just outlined, gymnastics has to do a much better job of not having such a quick-twitch reaction to suddenly doing tons of new impact volume at young gymnasts. All to often (and I’m guilty of this) coaches see that gymnasts aren’t running fast enough aren’t jumping high enough, or aren’t completing skills, and they result to throw a massive amount of jumping, sprinting, and plyometric conditioning at them. Or, they will have the gymnast do way more skill repetitions of their vaults, tumbling passes, and jumps over a few sessions.

I’ve worked with far too many gymnasts who tell me their coaches were upset that things weren’t progressing, so they made them do a crazy long new warm-up, 10 beam routines, or 10 vaults per night until they ‘got it right’. It almost always ends up with many of the young gymnasts complaining of shin splints, getting growth plate irritations, or worse having stress fractures that remove them from practice.

We as coaches need to be more accountable for these situations, and not treat it as a survival of the fittest scenario. It’s not about seeing who can keep up, it’s about using the available literature and science to train intelligently. Sudden unplanned spiked in volume like this needs to be cautioned against.

If you feel that the athletes aren’t powerful enough, or need more work to dial in skill repetitions, keep a cool head in the moment and then brainstorm a plan over 2-3 weeks that can be used. Educate the athletes on the goal, involve them in the conversation to get input, and research the latest concepts in the scientific research on the best ways to go about it. That is a much better solution for everyone’s physical and mental health.

3. Slowly Rebuild Impact Volume Should Injury Occur

This is more a combination of the medical side and the coaching side, but we all need to do a better job of communicating around injuries. I have previously talked about this in a popular article – “11 Crucial Ways to Combat Knee and Ankle Injuries in Gymnastics” but wanted to expand more on this topic in particular.

If medical providers don’t offer clear, objective guidelines for returning to impact, reinjury problems are going to pop up fast. Vice versa, if coaches do not openly communicate with medical providers to help build a plan, and then actually follow it over a month, that too will be an issue.

Nothing gets me more frustrated than to hear medical providers ‘clear’ a gymnast but offer zero guidance on how many impacts to do, how many days per week, and what strength work to use for rebuilding their tolerance to impact. In the same light, it’s beyond upsetting to hear coaches who blatantly ignore medical advice telling kids to just work through the pain of a growth plate injury and to just return back to full impact volume as soon as cleared.

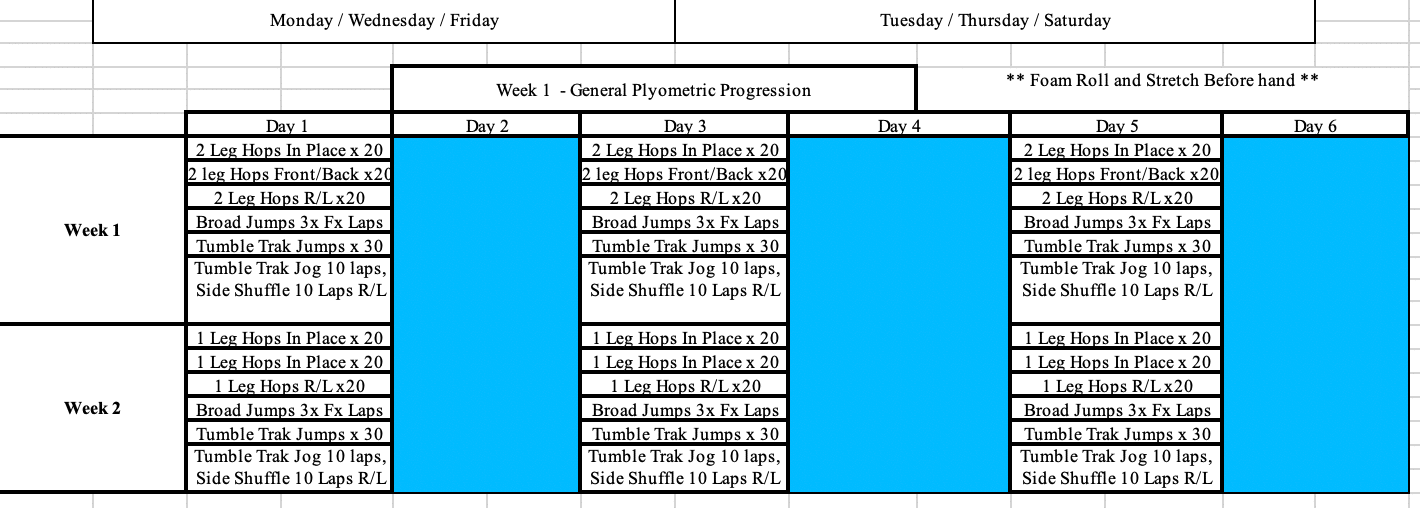

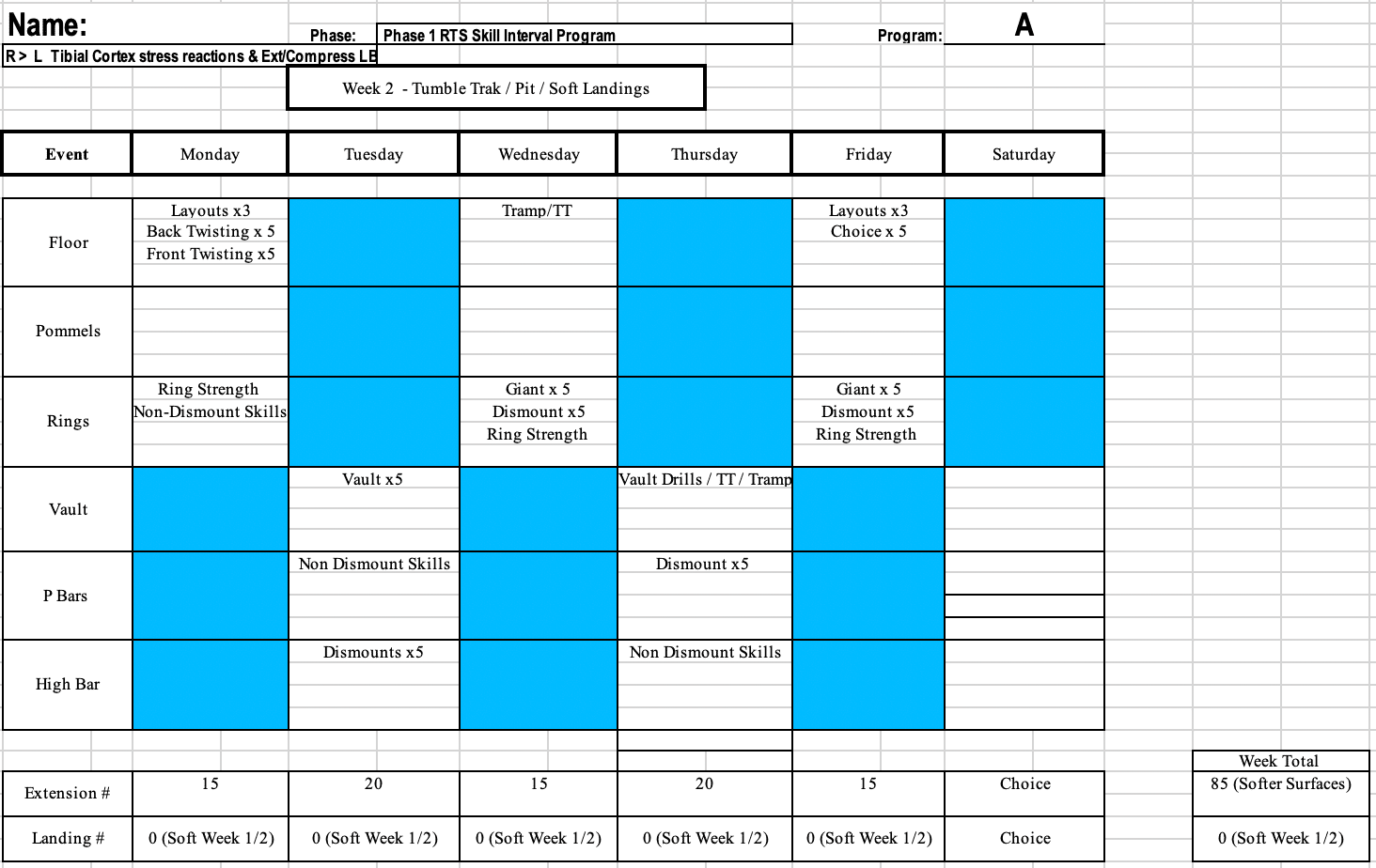

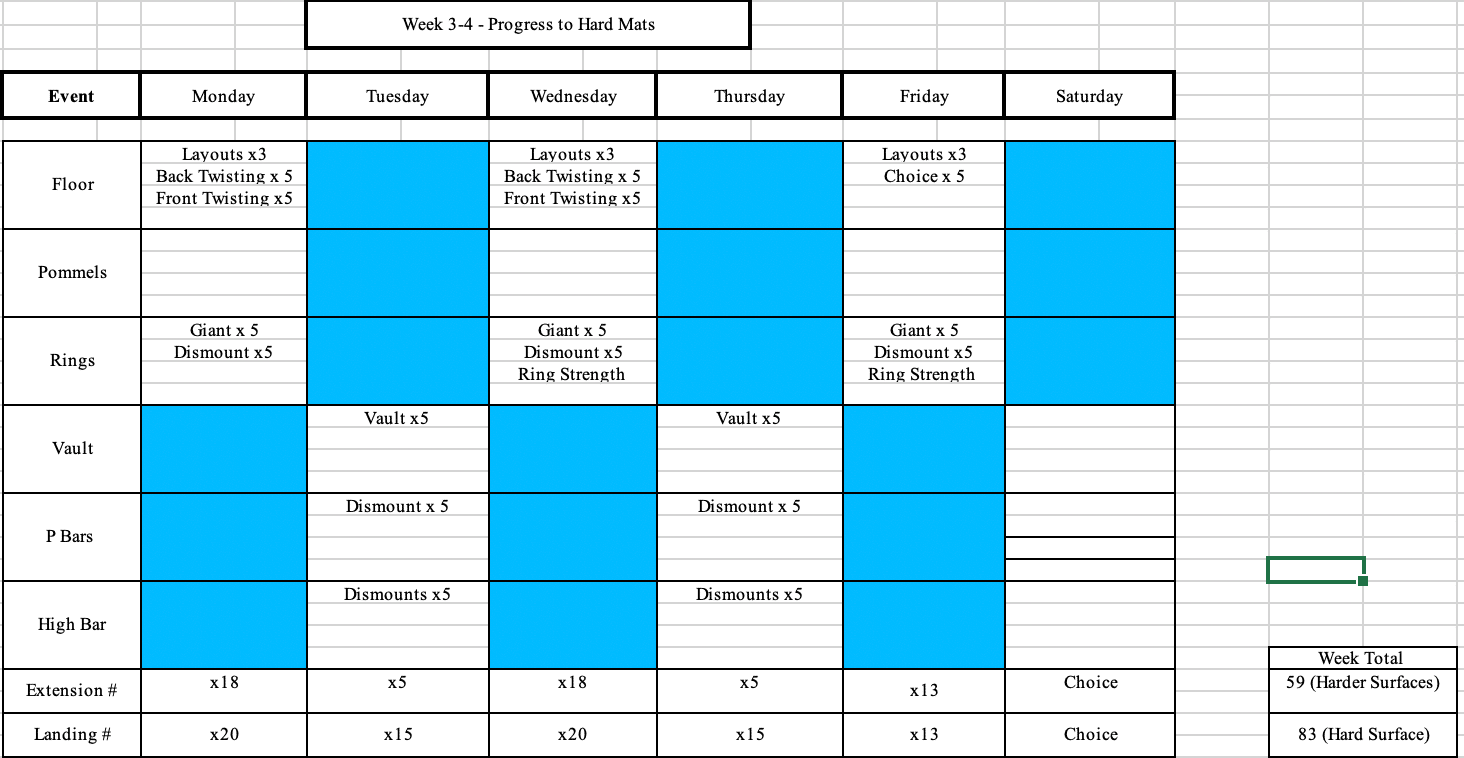

Do the gymnast a favor and take the time to communicate about the injury, build a plan of action together, and implement it. Here is one example of a return to impact program I made for a higher level gymnast who had stress reactions in both his shins. He did 2 weeks of general plyometric work (low volume and low intensity), followed by 2 week of softer surfaces (moderate volume and moderate intensity) and then finally back to full hard landings (high volume and high intensity). He was also doing a 4 day per week strength program I wrote to him, which had lots of strength and progressive impact work. Keep in hese sheets show his impact volume,

not all the skills he was training.

So I know that might seem a bit overwhelming, but I quite honestly think this is one of the only ways we can make a dent in such high overuse knee/ankle injury rates.

We also try to be aware fo the numbers and ‘caps’ for certain skills. We’ll have people start with 5 of an upgraded pass to stacked mats, and do 3 passes of basics on the real floor. As the pre-season comes closer, we will start to transition more to the floor to build impact volume. Say doing 3 of their upgraded passes, 3 of their basics, and then trying to transfer the upgraded pass to floor 3 times. Same for dismounts, series on beam, and so on. During longer or harder workouts, we’ll say do all the repetitions on hard, aiming to make 5, but ‘capping’ the attempts at 8 so we don’t overload someone.

These are all just practical ideas that I have found really helpful. We still deal with flare-ups and have to modify based on the individual, but overall these ideas have dramatically helped out knee, ankle, and lower back overuse rates. Hope they help you as well! Take care,

– Dave

Dave Tilley DPT, SCS, CSCS

CEO/Founder of SHIFT Movement Science