Why I Don’t Use Ankle Weights With My Gymnasts

To start, I’m aware this is another controversial topic in gymnastics. I have spent quite a long time organizing my thoughts and how to present them in a positive, constructive article. As a younger coach, I used to do a ton of ankle weight work, but have changed my approach quite a bit in the last few years.

Before you dive into the article, remember I recently released all of my thoughts on Gymnastics Strength and Conditioning, as well as Gymnastics Flexibility, in free e-books. You can download them here,

The Gymnastics

Flexibility Guide

- Cutting edge soft tissue, strength, and active flexibility techniques for splits, handstands, and shapes

- Practical traditional stretching methods combined with latest scientific research

- Techniques for increasing flexibility, and making changes transfer to gymnastics skills

We take our privacy seriously and will never share your information. Click here to read our full privacy policy.

The Gymnastics Strength

and Power Guide

- Methods and exercises for increasing strength and power in gymnasts

- Explanations on why gymnasts should use both weight lifting and body weight strength

- Teaches concepts of planning, specific sets or reps, and planning for the competitive year

We take our privacy seriously and will never share your information. Click here to read our full privacy policy.

I hope to outline the reasons why I don’t use ankle weights based off the research and literature I’ve read, as well as the increase in hip-related injuries I have treated gymnastics patients for lately. Then rather than only being a “negative Nancy”, I’ll offer alternative ideas as to what I do in practice for improving hip strength, power, and skill development.

The biggest concern I have with the use of ankle weights is related to two concepts of hip impingement and hip instability. I feel this issue comes up during fast dynamic movements like jumps, kicking drills, leaping, running, men’s pommel work, and so on. Anyone who wants a fantastic read and more elaborate background on these concepts should read this article: “The The Hyperflexibile Hip: Managing Hip Pain In Gymnasts and Dancers“. I will try to provide simple explanations and also include graphics for the concepts.

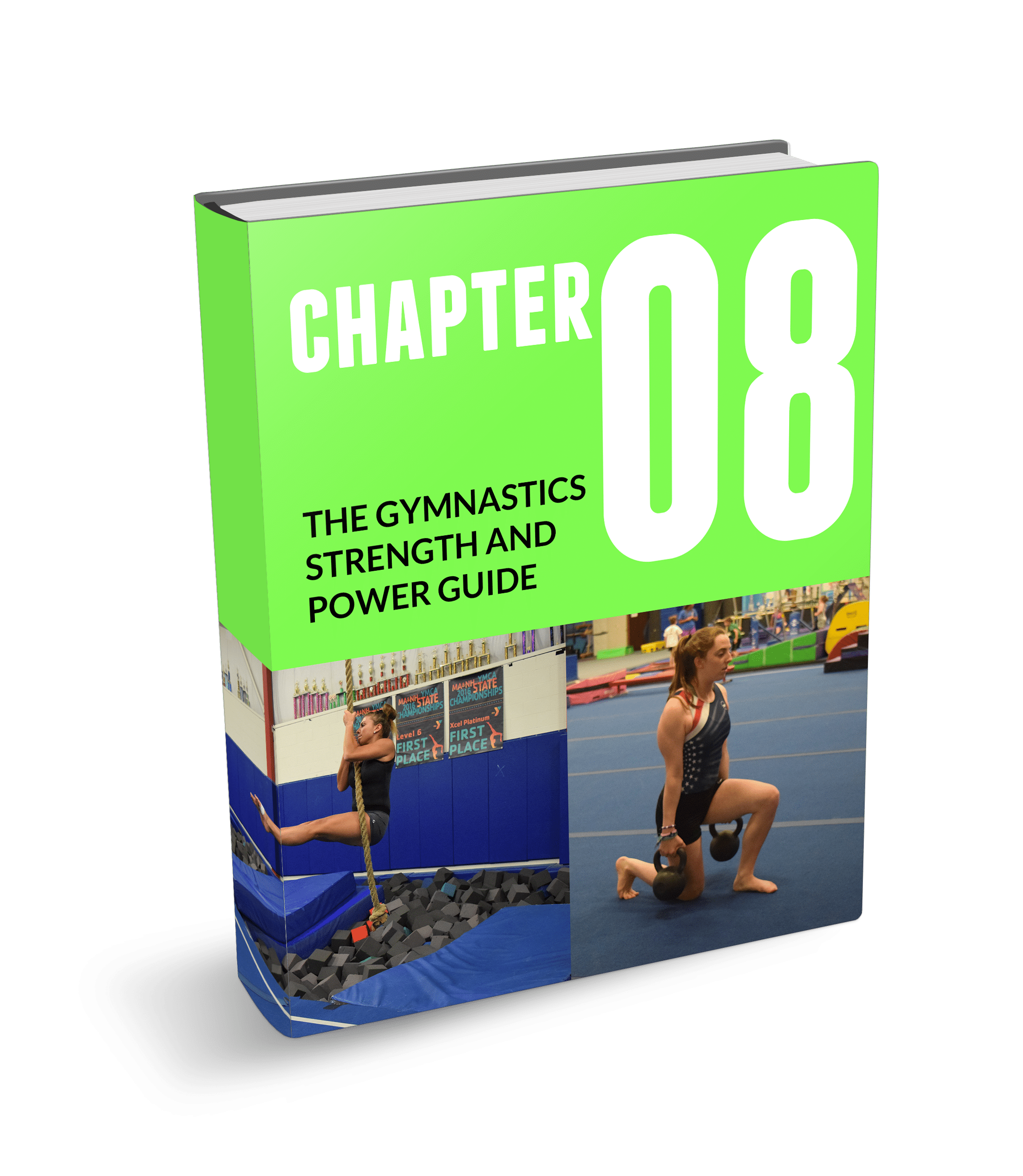

Hip impingement refers to the femur bone and pelvic bones make contact with each other at extreme ranges of motion, most times causing pain and possibly damaging the soft tissue in between. Hip instability refers to the hip moving into to those same end ranges of motion without strength/control, causing the head of the femur to partially slide out of the hip socket. These two things often happen together in very flexible gymnasts, theoretically as the contact of the femur on the pelvis creates a “fulcrum” type point for the head of the femur to lever against contributing instability.

It may cause irritation to the impinged tissue, but also excessive strain to soft tissue and the hip ligaments/capsule that are being stretched with the instability.

- This can happen with hip flexing movements (think front leg high kick or leap) as the front of the femur bone makes contact with the front of the pelvis (impingement) and then the contact acts as a fulcrum for the femoral head to slide out the back of the hip joint (instability).

- This can also happen with hip extending movements (think back leg kick or leap) as the back of the femur bone makes contact with the back and outside of the pelvis (impingement) and then the contact acts as a fulcrum for the femoral head to slide out the front of the hip joint (instability).

Now let me tie this into why I no longer use of ankle weights. The ankle joint is very far from the hip socket. The farther the load is away from the joint, the more force it will have on it. It’s my opinion that using ankle weights under high speed (like in leaps, jumps, leg kicks, running, gymnastics skills/drills) will be very challenging for gymnasts to control due to the long weighted lever arm. Unfortunately, I feel the load at the end of the limb may contribute more to the forceful hip impingement, and also contribute more to the “fulcrum” based instability/subluxation stretching the soft tissue and possibly irritating the hip joint.

I think this is especially true in those with natural hyperflexible hip joints who are not fully developed and lack hip strength. This may be one reason why so many gymnasts say their hips hurt when they do jumping drills, running, or skills with ankle weights on. Again, these are just my thoughts. To really see if it is true I would need a dynamic MRI machine, a super slow motion high def camera, and someone way more technologically savvy than me (anyone want to put in donations?).

Secondly, I have also found that many gymnasts have significantly increased passive range of motion due to naturally laxity, but have a notable lack of active control for their full hip ranges. This is especially true when not allowing compensation from other body parts or excessive swinging for momentum. They often struggle quite a bit to lift their legs even against gravity alone. In this situation, if the gymnast can not access their full range of motion against gravity alone, I see no justification for adding additional ankle weight resistance and allowing swinging momentum to reach the desired end range of motion. I feel this may not only foster more compensation, but it may create overload based injuries to muscles and tendons in conjunction with the principles above.

Third, on an even geekier motor control point I think the use of external loading far away at the ankle joint greatly distorts the movement pattern the brain is trying to adopt neurologically. In simpler terms, I think that ankle weights make the skill very different compared to just the weight of the leg, and don’t accurately represent/have transferred to nonweighted leaps. Many people say how easy their jumps and skills feel after taking them off, but I think this is a short-lived neurological “trick” that may not have the best long term carry over.

Now please don’t take this as me not being a fan of external loading for gymnasts, as I am a fan of that when properly used (see article here). So, what are some solutions to maybe moving away from aggressive stretching/ankle weights but still developing beast like leaps/jumps?

Alternative #1: Drills To Help Gymnasts Gain Control In Full Range

For those gymnasts that don’t have enough passive range and need mobility, I’m personally not a fan of pushing aggressively for splits. To be honest, I think it may put lots of strain on the passive ligaments, capsule, and labral tissue like noted in the above instability section as opposed to the soft tissue we want to relax. Tweaking stretches and not allowing compensations is important. Take this true hip flexor stretch, as opposed to the traditional “deep” lunge stretch

I personally changed my approach to now use progressive circuits that aim to gain motion in a nonthreatening manner, immediately teach the nervous system how to use it, and then use the new motion for gymnastics specific drills. See this video here as an example.

In terms of building control in the full motion, I’m a fan of using specific drills that help close the gap between the athlete’s lacking active range and massive passive range. Some gymnasts may need assistance via a partner or bands to match their lack of active range to their available passive range. You can see this in the end of the first video with a partner assistance, and also in the second video using the band. Once they master then they can wean off the partner or band.

Then lastly, once decent active control is established skill specific drills can be used to actually improve the skill specific beam/floor/press handstand/men’s pommel horse work. This is where I feel many of the great available gymnastics drills comes in. Once a gymnast does show the full range of motion and good control, I think elastic resistance can then be used as an additional challenge.

This is what many gymnastics coaches already do, but I feel that it must be put in an important progression noted above. I feel gaining full active range of motion, progressively adding anti gravity speed, and then finally practicing skill specific challenges is one safer progression to ankle weights.

Alternative #2: Use Periodized Strength Cycles To Increase Power Output

I think the main reason coaches use ankle weights is because they want more powerful, sharp leaps and jumps. I feel by far one of the best ways to gain explosive power for skills, but more specifically leaps and jumps, is to have a well organized, systematic and periodized strength program that creates the lower body power. Power and the ability to express explosive force off the floor/in the air is a product of strength as a foundation. The picture below is part of the 2015-2016 strength and conditioning template I programmed for our optional gymnasts.

For me, the first step is to gain general leg strength through single and double leg push/pull movements innoncompetitivee season. This is done via systematic, planned, progressive adaptive overload with appropriate recovery over various monthly strength cycles. Examples include split squats, single leg deadlifts, single leg squats, hip lifts/thrusters, and so on. Start with no weight and proper technical form, then progress under proper programming to external load.

<c/enter>

The second step is to then transfer the gains in strength into more power focused activities over another set of weekly cycles. This helps teach the recruitment of more motor units, improve efficiency of neural coding and muscular coordination, and increase motor pool discharge in a short period of time. This is done so that the neural system learns to rapidly produce force against the floor to propel the body mass higher, and also rapidly produce force to lift the leg in the air. Some of my favorite exercises for this are lateral rockets, leaping drills from one knee, double box jumps with no counter movement, and single leg jumps from a seated position (for those advanced gymnasts that can do it correctly).

Then again like noted above, this explosive power can be transferred into skill specific patterns for whatever skill the gymnast is looking to work. There are many different gymnastics drills coaches have that I think fit in well here. This is a big topic, and I encourage people to check out Tudor Bompa’s book, or find a knowledgable strength and conditioning coach to teach you some concepts about program design.

Caveat Note On Core Strength: I will say, that there are some instances like with core strength the use of external loading via weights can be useful. For low impact, non dynamic or ballistic based strength movements (thinking hollow rockers or flutter kicks, leg lifts, rope climb, etc) I can see the benefit to using light external ankle weights. However, I will stress that I would only use this on a gymnast who shows absolutely perfect technical movement without load, in full range of motion, and has the ability to maintain alignment integrity under fatigue.

A Note From Dr. Sands: For those interested, I also had a conversation with Dr. Bill Sands on this issue. Here is his response from my questions,

” Hi Dave,

I’m not a big fan of ankle weights for reasons you seem to be observing. I’ve not written specifically on the topic but mentioned the issues within other articles. I prefer using theraband and vibration, and can show significant results from doing so. I’ve attached the theraband article here along with some slides that amplify the results. The momentum developed from a weight swinging on the end of a leg is substantial and it’s no wonder that people get hurt from this practice. There is an old Russian article or part of an article that describes the problems of loading an athlete at the ends of limbs. Skills are too often distorted mechanically by doing so, and you run the risk of injuring joints moving from distal to proximal. Weak gymnasts have a lot of trouble controlling weights on the ends of limbs. Rehabilitation of knee injuries for example (as I’m sure you know) is reluctant to hang a weighted boot on the foot for knee extensions because of the tension transferred to knee structures. I’m not sure that anyone even does such exercises anymore.

I know some very prominent gymnastics coaches use and encourage the use of ankle weights. Sadly, I think they’re setting the gymnast up for injury. Of course, using ankle weights a couple of times is not likely to injure someone, so the issue isn’t so much ankle weights but the fanatical application of them day in and day out. There are easier and more effective ways to train jumps and splits than using ankle weights. Moreover, using a weight vest is what I would recommend if you want to work on jumps.

Concluding Thoughts

So if you stuck around to this point for the whole article, thanks a lot and I appreciate it. Let me re-iterate that the intention of this article is not to go around setting fires. I was someone who used to strap up ankle weights multiple times per week and do the exact things I now am concerned about. I also don’t think ankle weights and overly aggressive hip stretching are the only cause of hip injuries in gymnastics. As I noted above, all of this is just my thoughts and opinion based on seeing things from a dual healthcare provider/coach lens. I do agree with Dr. Sands above that loading centrally with light vests, through formal periodized strength models, and ensuring proper landing technique are key. I hope that people take these ideas not as attack, but understand I am just trying to offer constructive changes to our sport that lead to less injury, and more performance. I hope this was helpful,

Dave Tilley, DPT, SCS

*** Post Publication Note: After publishing the article and hearing some feedback, a few readers noted they use very like ankle weights (1-2#) in an effort to help their gymnasts gain awareness or “feel” their legs in space during certain dance activities. The concept of gaining more sensory input via light weights without excessive force being produced on the hip joint is something I could see as having a good rationale. Just wanted to note that along side the caveat above on core strengthening.

References

-

Weber AE, Bedi A, Tibor LM, Zaltz I, Larson CM. The Hyperflexible Hip: Managing Hip Pain in the Dancer and Gymnast. Sports Health. 2015 Jul;7(4):346-58

- Bompa, Tudor O., Haff, Gregory G., Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training; fifth edition. Human Kinetics 2015

- Caine D., et al. The Handbook of Sports Medicine In Gymnastics. First Edition. John Wiley and Sons, 2013

- Oliver, Llyod. Strength and Conditioning For Youth Athletes: Science and Application. 2013

- Lorenze, Morison S. Current Concepts in Periodization of Strength and Conditioning for the Sports Physical Therapist. IJSPT November 10(6) 2015

- Reinman, Thorberg. Clinical Examination and Physical Assessment of Hip Related Joint pain In Athletes. ISJPT 9(6) 2014

-

Enseki et al., Nonarthritic Hip Joint Pain: Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. JOSPT November 2014