The 7 Most Common Handstand Problems and How to Fix Them

I’ve been meaning to write this article for a long time, as it’s one of the most common issues I get questions about. Despite so many high-level athletes making them look easy, handstands are actually a super complicated skill with many moving parts. There are quite a few reasons why someone can or cannot show a great handstand with proper alignment, control, and the ability to move in and out of it during skill work.

Before I break things down and offer some videos, keep in mind that you can download my new 18 page PDF guide that offers step by step break down for the issues, how to screen them, and how to fix them. I will go into some of these below, but the PDF is a much more ‘user friendly’ guide. It’s is really handy to have in the gym or the clinic when trying to help athletes.

Just enter your name and email, and it will be delivered to your inbox!

Download My New PDF

'The 7 Most Common Handstand Problems

and How to Fix Them"

- - Learn the 7 most common handstand problems and how to fix them

- - Understand why these issues happen and how to screen them

- - Full video links to each exercise listed for specific problems

On to the bulk of this article. The most important thing to remember is that of all the common issues, there is typically a specific reason why it occurs, a way to screen for it, and some ideas or exercises to help.

Table of Contents

Problem 1 – Limited Overhead Soft Tissue Mobility

Why?

Gymnastics (and many others interests like circus or general fitness training) requires a ton of repetitive ‘closing’ of the shoulder angle. Think about closing the arms for shape changes, or to produce a flip shape. Gymnastics also often require lots of overhead hanging and swinging motions, like during giant swings or release moves on bars. The more advanced the skills are, the more strength or power needed to perform them.

The main muscles responsible for producing these shoulder actions are the latissimus dorsi, teres major, and pec major/minor. There are some other small internal rotators like the subscapularis and other accessory muscles, but generally, most of the work comes from the first three. If left unchecked without regular soft tissue care, stretching, and maintenance care, these muscles may become excessively stiff and prevent the shoulders from fully opening into a handstand line.

This is by far the most common issue I see in athletes, especially when they are naturally hypermobile and can ‘cheat’ the motion with ligament laxity or compensate with other areas like arching their lower back. Far too often in aesthetic sports like gymnastics or dance, the type of stretches being done to improve shoulder mobility are not specific to the anatomy of the shoulder joint. Stretching overhead with the hands internally rotated or just passively pulling someone’s shoulders open without thinking critically about where they should be feeling the stretch is not only a bit dangerous but unproductive. During stretching, the athlete should feel the stretch under their arms in the lat/teres major area, not in the top of the shoulder joint. You can read all about this in a popular article I wrote called “Gymnastics, Please Stop Doing These Stretches”

How To Screen

Seated Overhead Stick Screen with palms down, up, and together – I have shared this screen before, but it continues to be my go-to piece of advice to rule this in as a problem. Not everyone is a medical provider who can do hands-on assessments, so this is the next best option in my opinion.

Have the person sit against a wall with their hips close and head touching (natural lower back arch is okay), and then while holding a stick with their palms down, raise their arms up to touch the wall. Following this, repeat the test with palms up in under grip and hands close in a narrow grip. These last two positions of palms up and narrow grip demand more of the lats, pecs, and teres major because there is an externally rotated position. If they can not touch the wall, the soft tissue fo the shoulder and underarms may be a problem that needs attention.

Since reading more research and learning about the science of flexibility, I have largely moved away from only doing static or passive stretching. I have found much more effective and long term changes when using a circuit type approach that utilizes soft tissue care, anatomy specific stretching, strength work, and control work. You can see a tutorial video first, then below is another circuit example.

Problem 2 – Limited Thoracic Spine Mobility

Why?

Similar to the point above, many gymnastics skills and tumbling skills required the hollow shaping of the upper body to create good tension and flipping motion. When this is paired with a natural thoracic rounding bias to our daily lives (computers, driving, school, work, etc) it can quickly create a situation where the thoracic spine loses it’s natural ability to extend and rotate.

This extension and rotation ability is essential for a good handstand line, as full extension of the thoracic spine allows for the shoulder blades to fully glide properly (specifically externally rotate and upwardly rotate). The ‘socket’ of the ball and socket shoulder girdle is on the shoulder blade, so full overhead shoulder mobility is dependent on thoracic spine extension and rotation motion.

By regaining the thoracic spine mobility, we can allow full motion of the shoulder blade and as a result the shoulder joint. This now only allows for a full shoulder opening angle, it also allows the muscles of the upper body to work optimally in handstand lines, which leads to the next point.

How To Screen

There are no perfect ways to go about screening for this, but the most commonly used is the doing a rock back thoracic rotation screen I learned from the SFMA system. For this, have the athlete sit their hips back on their feet, put one elbow between the knees to standardize things, and the other hand across the chest. The athlete then turns towards the arm that is across their chest. The goal is to rotate well beyond 45 degreed (I look for 55 in gymnasts).

You can also do a sitting version of this with hands across the chest, and a ball being squeezed lightly between the knees to prevent hip motion.

How To Fix

My first approach to thoracic mobility comes from basic breathing drills. The ribs attach to the thoracic spine, which move every time you take a breath. By putting yourself in specific positions and focusing on deep breathing, the movement of the lungs can help mobilize the rib joints and the thoracic spine. Here are a few I have found really helpful.

Problem 3 – Limited Wrist Extension Mobility

Why?

Although not commonly thought about, the wrists are a very important piece of a handstand because they serve as the main interface between the ground and the person doing the handstand. Just as ankle dorsiflexion mobility is important for proper squat depth or running stride, wrist extension mobility is important for proper handstand lines.

If the muscles that produce a strong grip (flexors and pronators) are overused, or if the wrist joint itself becomes irritated, mobility issues can quickly pop up. What usually results is the athlete can not bend their wrist back enough during a handstand, and then the body’s center of mass is unable to fully stack over the hand. Many compensations can occur to balance the handstand like closed shoulder angles or hyperextended lower back positions.

How To Screen

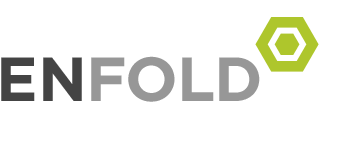

I have talked about this before, but my go-to screen is doing a hands and knees rocking test. Because the handstand requires straight elbows, doing the hands and knees version allows the arms to be straight and the shoulder to lean over the palm. Have the athlete place their fingers about 5″ away from a corner edge, then without lifting their palm up or rotating the hand, see if the athlete can achieve 100+ degrees of wrist extension not being limited by pain. Repeat on the other side.

How To Fix

I recommend that people first start with daily soft tissue care and stretching to see if changes can be made in mobility. I find this is best done with lacrosse ball rolling to the inside of the forearm, forearm and finger stretching. Then any handstand drills that require wrist extension like bear crawls or pike handstand holds can be done.

Problem 4 – Upper Back and Deltoid Strength Deficits

Why?

This issue tends to pop up because the upper back and shoulder blade musculature is often overlooked during traditional sports training. These muscle groups include the rhomboids, middle traps, lower traps and rotator cuff. They aren’t nearly as fun or flashy to train like the pecs, lats, and deltoids mentioned above. But, they are critical to proper handstands and shoulder function. Along side this, the actual deltoid muscle itself also needs a large amount of strength to hold the body weight and maintain balance.

For anyone working handstand skills, the ability to maintain a full handstand shoulder angle, and the ability to ‘push’ into the floor tall covering the ears, is dependent on the synergy between all of the muscles in the shoulder girdle.

If one group is significantly stronger than the others, say the lats and front of the chest compared to the scapula and upper back, issues can come up in relation to proper lines, control, and the ability to manipulate the handstand shape.

How To Screen

There are very specific ways to screen for this strength, like using a hand held dynomometer, but that is well beyond what most people can do practically. So instead, for upper back strength I recommend people take a look at the ratio between how many horizontal pushing and pulling exercises an athlete can do. If the athlete can easily knock out 30-50 push ups, but can barely get through 10 perfect feet elevated horizontal rows, you may have an issue.

For the deltoid itself, an athlete’s ability to do some variation of a modified bodyweight handstand push up are good starting points. If the athlete really struggles to do a basic box handstand push up with high quality, or a press walk drill, they might need more shoulder strength. I included this first video on purpose because it shows this weakness a bit. The athlete should be placing her head farther in front of her hands to make an equilateral triangle. But, due to some limited strength she is unable to, and requires some external spotting.

How To Fix

For the deltoids, I use the above handstand push up progression on the box to develop strength. I start people on a tuck position on the box, then move to pike, then one leg straight overhead, then finally spotted handstand push-ups or with the wall facing push-ups. Usually starting at 3-4 sets of 5 reps is enough of a challenge, and then over a few weeks, they can then progress up to 8-10 repetitions. This is a phenomenal video from my buddy Dave Durante if you want to learn these concepts more in-depth.

Problem 5 – Core Strength/Control Issues

Why?

For the most part, people who are training in bodyweight skills like handstands know the importance of core work. In some cases, more direct core strength may be needed. If so, it usually has to come more in the form of bracing and whole core work (hollow shaping, planking, loaded movements like farmer carries), and not just straight flexing movements like leg lifts or crunches.

In my experience though, people usually have a disconnect with core control. Core control is much different than brute strength. Control is more about being able to activate the entire core ‘cannister’ in a global brace and maintain neutral with high levels of tension. It is this aspect of control that uses the strength during skills like a handstand, especially when being able to master breathing and core engagement. This skill is best learned first with basic core drills, and then it can be transferred and trained in specific handstand type drills.

How To Screen

For this, it’s good to compare someone’s basic line on the ground versus their handstand line. If someone has a very tight shape, is able to get flat with full shoulder mobility, and has good body tension on the floor, but then it completely falls apart in the lower back with an arch during a handstand, the core might be an issue. Sometimes the addition of inversion and gravity makes it hard for athletes to maintain control, and their line starts to stoop into an overly arched position. They must be able to maintain a stiff core brace while breathing for at least 10 seconds on the floor, and then consistently show it during drills and progressions.

How To Fix

If athletes are truly weak in the core, which in my opinion isn’t as common to do a basic handstand, they might just need more time and work into shaping or core strength. I have put together a ton of body core strength drills on a YouTube playlist for those interested. To find that, click here. Or, check out some of my favorites below.

For other athletes that are strong enough, they might just need more awareness around how to engage and maintain a good braced core position. I find this is best done in a basic hook lying shape, then in dead bug / bird dog exercises, then more plyometric impacts, and then with handstand specific drills.

Problem 6 – Hip Extension Limitations

Why?

As we move down the list, this is something that isn’t usually the most prominent issue, but it can definitely can be a limiting factor to handstand mastery. If the hips aren’t able to fully open, and also if the athlete isn’t aware how to fully engage their glutes into hip extension, a piked hip angle may pop up and throw things off.

This sometimes has to do with good mobility of the hip flexors, quads, and adductors, but it also has to do with glute strength and control like mentioned. These muscles cross the front and inside of the hip, and if they are stiff may prevent the ability to fully open the hips flat. Similar to the first point about the shoulder soft tissue, these muscles are commonly overworked during running, jumping, and keeping good form in gymnastics (legs together, legs straight, toes pointed). They can easily get overworked and a bit too stiff, limited proper hip mobility.

How To Screen

There are two screens I like for this. One is a Thomas test, which looks at the hip flexors, quads, and outside hip musculature. Have the athlete sit close to the edge of a block, hug both knees to their chest, and then leg one leg drop back down. If the thigh is not flat to the block, that suggests stiff hip flexors. If the knee can not fully bend past 90 degrees, that suggests stiff quads. And if the leg drifts out to the side, that suggests possibly stiff TFL muscles.

The other test I use to look at inner thigh mobility is the FABER tests, which stands for Flexion ABduction and External Rotation. I’ll be the first to say this test isn’t a definitive for only inner tigh stiffness, as issues can pop up with the hip joint pathology and over arching of the spine. But for the sake of handstands, we’ll keep it simple.

For this, have the athlete lay on their back and then cross the foot of one leg onto the thigh of the other to make a Figure 4 type alignment. Be sure to hold the opposite hip down that is not being tested, so the lower back does not rotate and give a false positive.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patrick%27s_test

In most people, the knee should be able to drop parallel to the block (in line with their other leg). If not, this may suggest inner thigh mobility might be an issue. Like I said though, take this with a grain of salt because hip joint issues, ligament laxity, and core position can make a difference too. If you really think this is a main issue, I would suggest working with a medical provider to be sure about the main root causes of the problem.

How To Fix

Although I use this mostly for splits, there is a lot of this complex that is based on hip extension mobility as well. I’ve found it super effective when done each day before training.

Problem 7 – Technique Issues

Why?

There is no way around it, handstands are super hard! Even with great mobility, strength, and balance, there is an insane amount of work and patience needed to really build the skill to a high level. The best gymnasts and hand balancers in the world spend hours and hours per week on all the pieces needed to maintain their line, control it, and use it with harder skills. It might just take a ton more time than people are currently putting in.

How To Screen

Similar to the strength of the upper back, this one can get a bit tricky. I suggest that people compare the athlete’s basics and shaping during drills to actual skills. If their basics, flexibility, and underlying strength are sound, but then when they do the actual skill things fall apart, that might be indicative of more technique work being needed. Sometimes fear, not enough practice, or not enough repetitions can limit things ‘sticking’ during skill work that has handstand shipping.

How To Fix

For this one, the solution is simple and often boring. It’s going back to basic shapes, drills, and step by step progressions, every day. It’s not the answer most people want to hear, but it is the one they need to hear. Nothing replaces mastery of basics and slow progressions. Here are some of my favorites from my buddy Dave Durante at Power Monkey

Problem 8 (Bonus) – Fatigue

Why?

I wanted to make sure I threw this one in, as it is something not many people think about. There are many times when someone who is fresh has a great line and good control, but as practice goes on, or as a long training week goes on, it doesn’t look quite a great.

These are situations where you need to be thinking critically about the difference between the starting and ending of training, and also make sure you aren’t wrongly pinning problems to mobility issues. Especially with younger athletes, its easy to burn out during a long practice and see proper basics get sloppy.

How To Screen

For this, I would look at how someone’s handstand line is at the beginning vs end of a routine, practice, or training week. If things start off great then the wheels fall off when fatigue sets in, this may be more about endurance than strength or mobility. This is often overlooked, but in my opinion, is one of the most important pieces to remember. This one is more about bring present with athletes and really watching how they respond to the training prescribed.

How To Fix

If the issue is fatigue during a single routine, building up anaerobic capacity may be the key. Being able to buffer acidic environments and maintain muscle function is huge for gymnasts, especially in the upper body. If the problem comes down to the practice or weekly training level, much bigger conversations might need to happen about work to rest ratios, periodization planning, nutrition, hydration, and recovery methods. These will be on a much more case by case level, but the conversation about it is the first place to start.

If you’re looking for some cardio workout ideas, be sure to check out this cardio blog post article I wrote, and if you want an amazing podcast interview with Chris Hinshaw on energy systems training, check it out here!

Conclusion

So that does it for quite a monster article on handstands! Keep in mind that there may not be one single issue that is the rate limiter, but more a combination of factors that goes into it. I’ve found sometimes people do have shoulder mobility issues and core control issues that go hand and hand. My best suggestion is to take the time to really screen everything out, make a specific program that targets what the athletes need and do it every day for at least 2 weeks. Then you can go back and retest everything and see if progress has been made.

As with most things, I also highly suggest that collaboration with medical providers is done sooner rather than later. They typically have more experience with these tests and can buzz through them fast. They also have many more insights and specific hands-on assessments that can be done to narrow in on things not mentioned here. For now, I hope this was helpful! Best of luck,

– Dave

Dr. Dave Tilley DPT, SCS, CSCS

CEO/Founder of SHIFT Movement Science