Rehab Tips For Clinicians To Treat Gymnasts with Extension Based LBP – Part 2: Subacute Phase

In Part 1 of this article series I went over some basics around managing the acute phase, and the importance of figuring out issues above and below the area with pain. I also mentioned some educational, manual therapy, and basic exercises I tend to build in early. In addition to those things, after hypersensitivity has come down over a few visits, I start to expand the program. Here are some more thoughts relating to the sub acute phase of rehab.

Re-establish Dynamic Stability When Tolerated

Some interesting motor control / pain science research from Hodges suggests how during acute pain experiences or perceived threat the nervous system undergoes a highly individualized response. It is theorized that both intermuscular and intramuscular activity may be redistributed, degrees of freedom may be temporarily reduced to protect the threatened area, and short-term adaptive motor chances may occur. Although these short-term neuroplastic changes serve a purpose to limit the person, we want to make sure we address them through formal rehabilitation to restore movement variability, regain threat free automatic function, and set the stage for high level activity down the road.

Many clinicians working with gymnasts dive down the route of higher threshold core exercises that involve bracing, versions of planks, and so forth. My bet is on 85% of the gymnasts in rehabilitation with lower back pain have done years of high threshold core conditioning everyday ranging from planks, to leg lifts, stalders, and so on. Now, although I think these have value and I add power drills like medball slams, sled pushing, and kettlebell work in later during rehab, I personally feel that the lower threshold, automatic reflexive stability aspect is often greatly overlooked both in training and within the rehab context.

Just as many researchers have discussed the need to re-establish baseline glenohumeral dynamic stability following injury (research here, and here) , I think the same concept holds true for hypermobile athletes with extension based low back pain. They often lack static stability inherently globally and depend on high level dynamic stability and motor control through very large ranges of motion. I also try to set up the environment in a way that lets the nervous system self organize around the goal, rather than cue exactly the movement I want (more motor control research thoughts here and here).

IMPORTANT NOTE: This concept I’m outlining of re-establishing dynamic spinal stability is only being applied to a very specific situation where a hypermobile athlete is often in a rigid back brace 23 hours per day due to a symptomatic fracture, or is in the subacute stages of what often times is an over extension overload event. Usually their nervous system is hyper sensitized after the first few weeks and all movement is uncomfortable. This is also setting the stage for their spine to take high levels of force in gymnastics skills down the road. I do not think this applies to most general back pain populations where they are told their “pelvis is out of alignment” or they have “spinal instability” that needs stabilizing. I go a completely different route for general population treatment with other presentations. With my gymnasts, I’m looking to move past this phase when appropriate into more spinal dynamic movements they will need for skills (coming Part 3 and 4). This is one piece of a much bigger movement puzzle.

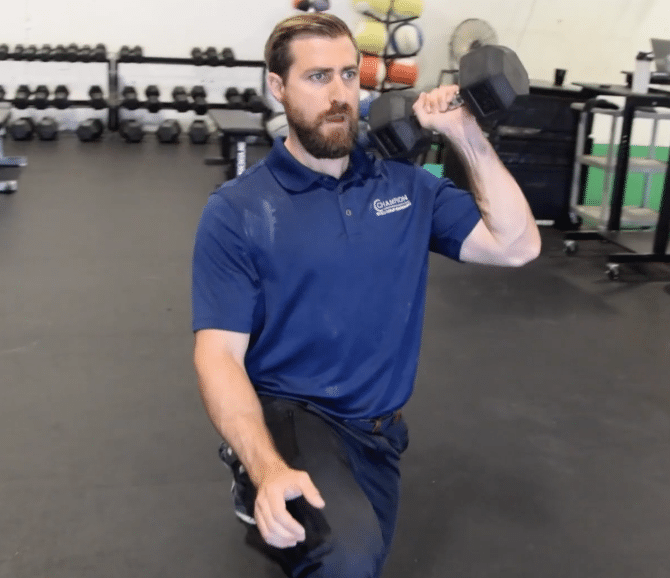

Moving back to the drills, here are some things I use early in rehab. Rhythmic stabilization drills in quadruped, 1/2 kneeling, and tall kneeling. I usually start without the stick and perform my perturbations more proximally, then move to distally using the stick. These are a little more aggressive in the videos due to these being with non injured athletes, but in the rehabilitation setting I keep them submaximal and subthreshold for symptoms.

For home programs, various palov presses, chops, and lifts are also useful.

When appropriate, more dynamic quadruped movements can also be very helpful. Both regular and inline bird dogs are one great option to start with. This can be progressed to slow bear crawling with external towel cue, which is a great way to work on lower threshold, reactive core control with lumbopelvic dissociation. It also is a great foundation for anti extension core movements that will be crucial in re-patterning hyper extension skills for return to sport down the road.

It’s important to note here that you want to make sure all planes of anti flexion, anti extension, anti sidebending, and anti rotation are covered. I also feel we also need to start to playing around with unloaded non neutral based spinal motions to see how the patient is responding, as they are usually in a rigid brace for true symptomatic fracture (another big topic on usefulness). Like I mentioned I will touch more on this in upcoming part 3 and 4, but it’s important we both keep tabs on symptoms with non neutral movements and also continue to help the athlete know the world isn’t going to end if they move their spine. We don’t want to induce movement fears, and we want to make sure they feel confident in their recovery process. That’s all for part 2, hope this helps.

Dr. Dave Tilley, DPT

References

- Hodges, Tucker: Moving differently in pain: A new theory to explain the adaptation to pain. PAINÒ 152 (2011) S90–S98

- Wilk, Macrina. Nonoperative and postoperative rehabilitation for glenohumeral instability.Clin Sports Med. 2013 Oct;32(4):865-914. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2013.07.017

- Reinold M, Gill TJ, Wilk K, Andrews J. Current Concepts in the Evaluation and Treatment of the Shoulder in Overhead Throwing Athletes, Part 2: Injury Prevention and Treatment. Sports Health 2(2)

-

Stergiou N1, Decker LM. Human movement variability, nonlinear dynamics, and pathology: is there a connection? Hum Mov Sci. 2011 Oct;30(5):869-88. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2011.06.002. Epub 2011 Jul 29.

- Hamill J, Palmer C,1 Van Emmerik R. Coordinative variability and overuse injury. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2012; 4: 45.