Combating Achilles Tears In Gymnastics (Pt I): Investigating Possible Contributing Factors

The high rate of Achilles tears in gymnastics is something that has always blown my mind. As a gymnast going through high school and college, it seemed that every few months I heard about someone else loosing their season because they ruptured their Achilles. With new research and lots of information coming from people in the sports medicine side of gymnastics, a lot of great progress has been made to educate people about information regarding this problem. Unfortunately, the issue still continues with recent reports of Bri Guy from Auburn tearing both her Achilles at the same time last week, an Achilles tear from Sam Peszek earlier this year, a hand full of college and international gymnasts, and I’m sure many more across the sport. It started to get the gears of my brain turning about what else maybe goes into the problem, and some ways that I may be able to offer some knowledge for coaches and gymnastics to use preventively in their training.

Before I dive into the specifics, keep in mind I wrote an entire chapter on this for Medical Providers you can downlaod for free here,

The Gymnastics Medical Injuries Guide

- Understand the most common injuries in male and female gymnastics, why they occur, and how to prevent them

- Read about the most current science on injuries and rehabilitation in gymnastics

- Get tips on the latest injury risk reduction and rehabilitation practices

We take our privacy seriously and will never share your information. Click here to read our full privacy policy.

Then two months ago a gymnast I knew from a camp contacted me saying she tore her Achilles doing a full-in on floor, a skill she has done hundreds of times before. She was asking about the treatment and surgery, what her rehabilitation process would be for the year, and her hopes of continuing gymnastics for her last few college years. I took the opportunity to ask her a lot of questions about how her training was going before it happened, if she had other pains or injuries that were ongoing, the road leading up to her injury, and a lot of other stuff. I scribbled all of the things we talked about down on a napkin, got out all the research/books I had related to Achilles tears, and then took a few hours after to map out some of the ideas I had brewing. After this process I looked at all the pages I had out and started to notice that there may be a lot more to it than meets the eye. Along with this, I found that a lot of the contributing factors may have preventative steps that coaches and gymnasts could be using during their training.

Calf Muscle Anatomy – http://www.keyaspectscoaching.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/calf-muscle-stretches-to-improve-snowboarding.jpg

After a few more weeks or reading and putting stuff together, I started drafting this post to offer people in gymnastics my thoughts on what we can do to help tackle this issue. In this post, I’ll outline my thoughts over the last month related to the big contributing factors to Achilles tears in gymnasts, hopefully giving people insight into the need to have pre-hab in their training. Although I’m sure I am missing some ideas and will edit this post as I learn more, it’s a good place to start. Then in the posts to come I will offer pre-hab techniques that can be used during training to possibly help reduce a gymnast’s injury risk. Remember that my ideas also use lots of literature, and credit goes to a lot of very intelligent people’s work which I’ll include in the reference list below.

Factors Related to Gymnastics as a Sport:

Forces of Gymnastics:

As I have mentioned a lot, the forces of gymnastics have to be understood and appreciated to set the stage for why being proactive about the risk of an Achilles tear is crucial. Dr. Bill Sand’s work and other great research supports the data that forces can be roughly 9x -17x an athlete’s body weight every time they tumble (information used is with credit to Dr. Bill Sands research and discussions I’ve had with Dr. Josh Eldridge). To put that in a better view, that suggests that

- A 100 pound gymnast may be subject to between 900 pounds and 1,7000 pounds of force every time they tumble

- A 120 pound gymnast may be subject to 2,040 pounds of force

- A fully matured male athlete weighing 165 pounds may be subject to 2,805 pounds of force.

That information is based off of measurements during tumbling, but there is also information available on the theoretical forces for high powered tumbling, dismounts, shallow landings, and landing with improper technique. All of that force has to go somewhere every time, and areas like the Achilles tend to get quite a bit of the work load. This can cause lots of damage to the Achilles in small doses overtime known as repetitive micro trauma, which is a big component to overuse injuries. The Achilles tendon, calf muscles, and foot structures are extremely strong but we really don’t want to push the limits and gamble over time. This idea links directly to the next thinking point.

Repetitive Forces Overtime During Training:

I think many coaches and gymnast underestimate the amount of force and loading a gymnast is subject to during their training. Many coaches have become very engrained in our established training methods moving from one event to the next, encouraging gymnasts to take a very high number of turns, over the course of many hours, many days a week, for the majority of the year. I’m not going to map out the math but between tumbling, vaulting, dismounts, drills, beam impacts, and much more gymnasts ankles and Achilles are taking hundreds of impact based occurrences each practice. Take hundreds of impact occurrences, multiplied by 3-6 days per week (based on a variety of different factors), plus competitions, during year round training. It may start to be a little more clear to why so many foot and ankle overuse injuries are in gymnastics. Steps for proper activity modification when needed, recovery, addressing biomechanical factors, and pre-hab techniques need to be considered for gymnasts due to the nature of the sport and training. Even without an injury, the sport of gymnastics predisposes a lot of athletes to develop acquired tightness, stiffness, and movement problems overtime. Just because it doesn’t hurt, doesn’t mean there isn’t a problem. When nothing is being done to pro-actively combat the problems in the tissues of the lower leg muscles/calves/Achilles/feet it can become problematic. . Along with this, if the recovery and attention to the start of injury is overlooked gymnast’s begin to skate on thin ice for an injury such as a overuse or ruptured Achilles to occur.

Many coaches and gymnasts say Achilles tears “just happen out of the blue”. However, if high volume impact gymnastics training is occurring on top of poor movement patterns (like improper squatting and landing technique), along with not paying attention to proper recovery and preventative injury management, it creates a situation where it just happen to be the straw that broke the camels back. Often times these problems are brewing under the surface as the gymnast has some sort of dysfunctional movement, and also may have some structural problems that I will go into below. Overtime this creates ware and tear on certain spots like the Achilles, and then it may set someone up for a shallow landing or power tumbling pass to causes the Achilles to tear. If the Achilles is slowly damaged overtime with these problems, it may only take the last big pass or landing to push it beyond its capacity. This is why I would bet that so many gymnasts tear their Achilles on the back handspring of a tumbling pass as they move into a set, which some research suggests produces the highest force demand on the Achilles. The ankle is forcefully pushed into a toes up (dorsiflexion) and flat foot (pronated) position, and it loads the Achilles at a very high-speed to transition to setting for a skill. Often times this is stacked on improper leg alignments and poor lower leg stability during tumbling. This motion may be just enough to tear the Achilles that has been damaged over time and is so stressed. No offense intended for these two pictures of gymnasts below (one taken from YouTube of Bri Guy), they are just two prime examples of how aggressive back handspring sets can be for the Achilles.

This next few points are really the areas that I wanted to focus on for this post, due to being able to apply the PT driven information related to movement patterns gymnasts may have. I think there is a lot to be thought about when linking the risk of an Achilles tear to the way a gymnast moves, how the spine and lower extremity chain function together, and problematic factors in other body areas. I wanted to share the ideas that popped up in my head that may be big concepts for coaches and gymnasts to think about.

Flat Feet:

Gymnasts having really flat feet (over pronation) is a huge factor coaches and gymnasts need to think about. The first major reason is that when a gymnast’s feet are excessively flat, the feet looses it’s ability to act as a proper shock absorber. The incredible support properly functioning arches gives is due to the interaction of a variety of muscles, ligaments, tendon, fascial, and bony joint linking connections. The high forces of impact forces of tumbling and landing over time can cause wear and tear on these structures, and then the structures lose their ability to act as a good shock absorber. Remember the feet and ankles serve as the first line of defense for tumbling and many gymnastics skills that have such high forces. All that force have to go somewhere, and if the foot isn’t picking up some of the work load that is more force going through the Achilles and leg structures connected in the leg chain.

The second reason that flat feet can cause a big problem for gymnasts in relation to Achilles tears is because it creates an uneven strain on the Achilles and calf during impact loading. As the foot flattens it causes more stress to travel through the inside portion of the calf (medial side) due to the alignment of the foot and ankle structures. There is some evidence from recent literature that suggests when the foot is in this rolled in position (pronation with calcaneal eversion) it can load the inside portion of the Achilles tendon 75-100% more than it would take if the foot was in a neutral alignment. This research also suggests that the more the foot falls flat and finds this position, the more strain may be applied to the inside portion over time. This concept can definitely help explain how this foot problem can contribute to a overuse injury, progressive Achilles damage, and a possible rupture once the tissue gets to its limit.

If you stand behind one of your gymnasts and look at the back of their heels, you can often times see this. In gymnasts with flat feet, you can see the insides of their feet tend to roll in (the fancy term is a rearfoot valgus), which causes the inside portion of the calf/Achilles to have more strain. In the picture below, ideally the lines should make a 90 degree perpendicular angle if she had good arches and a good alignment (blue line). You can see however the lines are a bit off from this, and the angle falls towards the middle (yellow line). Her left foot actually is a little more pronounced but I wanted people to see it without lines on it.

The lack of arch support and constant pounding is often further amplified to be a problem if gymnasts do not have proper support when no in the gym (like sport shoes that look good but bend in half, or wearing nothing but flip-flops in summer). The improper support outside of the gym is coupled with the gymnast practicing barefoot inside the gym and not having any support for their arches most of the day. There can be a lot of other problems in the foot structures like the mid tarsal joint and forefoot that are a bit too complicated to dive into. Thankfully, there has been a lot of good work for finding ways to help gymnasts gain arch support during tumbling such as Dr. Josh Eldridge’s “X Brace” and certain taping techniques like Low-Dye,which is for another time.

Toe Point/Plantar Flexion Imbalance:

The next big factor related to Achilles injuries is that fact that gymnasts spend almost all of their time during in a “toe pointed” position to have proper form during skill work. Although this looks very aesthetically pleasing overtime it creates a huge imbalance in the mobility of the toes to be able to move in the upward direction (dorsiflexion), which can have a huge impact on the gymnasts double leg/single leg landing and squatting movements. The calf muscles known as the gastrocnemius and soleus can become very shortened and tight with so much toe pointing. This problem is usually paired with a lack of mobility work to release the soft tissue as seen with a lacrosse ball, stretching, foam rolling, and so on. A few calf stretches at the beginning of practice during a warm up unfortunately isn’t usually enough to release the tightness that is constantly being created during gymnastics training.

If the calf muscle is chronically tight and the joint of the ankle is stiff from so much landing, every time the gymnast tumbles, dismounts, or receives impact it will be forcefully pulling on the Achilles tendon past its comfortable range of motion limit. The joint itself can get some attention with some self mobilization techniques.

Lots of training and impact, improper recovery and pro-active pre hab, and these noted foot/ankle problems can all start to add up. This is often times when gymnast start to complain of achy or nagging pain in their Achilles. This should be a big red flag for coaches and gymnasts. This is often a sign that the Achilles is being subject to small micro tears or the growth plate may be being irritated (Sever’s disease). If gymnasts and coaches continue to train through this period without proper rest, mobility work, and recovery it may drastically be increasing the risk of getting a full-blown tear. I personally feel this is an area where a lot of pre-hab attention should be given simply due to the fact that many gymnasts usually has some degree of a calf mobility problem, along with some degree of a flat feet issue.

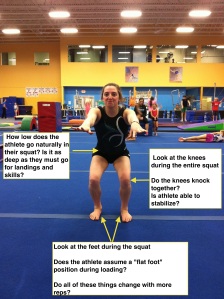

Improper Squatting, Jumping, and Landing Technique:

The next step in this process that is critical for gymnastics coaches and gymnasts to be aware of is the need to practice proper landing and squatting techniques. In very general sense proper jumping, landing, and squatting techniques are important because the allow the forces produced by gymnastics skills to be dispersed across the entire lower body chain and spine evenly. When gymnasts do not have proper technique at baseline and then stack on many repetitions with improper technique, certain areas start (commonly the lower spine, knees, and ankles) start to break down and develop overuse injuries. These faulty movement patterns with basic movements also tend to load the passive structures that shouldn’t be regularly used as a main shock absorber (ligaments, meniscus, tendons, etc.). We want the squatting, jumping, and landing techniques to be taught properly and used in every part of training from drills, to skills, to routines. This allows the strong dynamic structures like muscular chains to take most of the force absorption equally across all parts. It also overtime is hopefully part of the gymnasts “default” movement pattern and makes it happen automatically as it is stressed.

Many gymnasts that I watch land or squat have improper landing technique of not sitting back into their squat to absorb impact through the glutes and hamstrings, the knees traveling to far over the toes or collapsing inward, or under rotating with pressure going through the toes and not into the heels. These are just a few examples that can be problematic, there can be many contributing factors related to mobility/flexibility, strength and stability, and others. All of these things can all create increase forces through the ankles and a lot of force going into the Achilles. Again, no offense to the gymnasts here they are part of a huge population who has this issue.

I have also noticed a huge problem with many gymnasts when they land on a single leg and are forced to absorb all the impact for leaps, jumps, tumbling skills, or beam skills one leg at a time. After recording and watching many of our girls in slow motion, many of them show a position of the hip, knee, ankle, and foot that is dangerous for both the knee and the ankle. I’ve also noticed from watching a lot of video in slow motion of our athlete’s and online that it is extremely common for gymnasts to land complicated tumbling passes and dismount passes with a very slight delay in one foot hitting the ground before the other, which is known as asymmetrical landings. This is a huge risk factor for ACL and knee injuries. It also means that for a split second one Achilles is taking all the impact, which also may mean that with a pronated foot the medial side of one Achilles is taking all that pressure initially. I think these are all definitely something to think about as the sport looks to find ways to deal with this risk.

If the lower extremity chain collapses into this dangerous position, the force will often times be sent through the path of least resistance which many times is called the “weak link”. The Achilles becomes one of these common areas because of the flat foot, tight calf, stiff ankle joint, and faulty landing pattern situation from above. Addressing single leg stability and proper mechanics is a topic people teach entire courses on, but I will try to offer some ways to work on this in coming posts for gymnasts and coaches to use.

Coaches or gymnasts who know their athletes have poor landing mechanics and see some of these problems often can use jumping, landing, and squatting education from many great resources available to help train these techniques. If coaches and gymnasts do not feel comfortable or have the knowledge for this, many skilled medical professionals can help. I would highly suggest members of the sport reach out to use these resources and also qualified medical professionals to help screen and educate members in their gym with ways to help out. There are also a variety of stability and movement pattern pre-hab drills that when done properly, can help to work on these issues. The time taken out to get gymnasts evaluated, trained, and using these techniques can be huge for their gymnastics performance and injury risks.

Not Having Proper Strength Development To Tolerate Forces:

I think this is another huge component that gymnasts and coaches need to think about. There may be many occurrences in gymnastics when athletes simply don’t possess the trunk and lower extremity strength to handle the forces gymnastics can produce. This is especially true in our younger athlete’s who are progressing in the sport and growing quickly as they train. These athletes in the early years tend to be the most at risk for many types of injuries. There is a strong concept base supporting the idea that the best way to build up this strength is through a well programmed, properly executed, progressional strength and conditioning/weight lifting program. This type of program needs to come from expert coaching focusing on technique and movements specific to gymnastics. Just as an expert coach in gymnastics possesses a specific skill set, there are expert strength and conditioning professionals who possess a separate skill set in designing and implementing these programs. The body weight exercises many gymnasts do for strength at practice are fantastic to a certain degree, and they have their own sets of benefits for gymnastics development. However, even with resistance training and progressive training gymnasts use it is very hard to create and implement strength and conditioning programs in the gym that can build strength to help tolerate the forces of gymnastics. Also, many coaches may not have the working knowledge of movement patterns and proper technique that are relevant for this area.

I personally have grown quite a bit in my thinking process about this idea. A lot of this came from reading literature, listening to lectures from researchers in this area like Dr. Bill Sands, and discussing with some other professionals who support this concept of strength training/weight lifting for gymnasts. Although it may be a new area for gymnasts, many professionals in this area agree that this concept is crucial for development of gymnasts, increases in performance, and the reduction in injury risk. I also am fortunate to have some great people in my area who have taught me a lot about proper strength and conditioning programming, and the ability to use this for injury prevention. These specialists (and many other professionals) who are qualified have a large basis of knowledge that can be of great benefit for gymnastics coaches and gymnasts. I am very lucky to be able to discuss the sport of gymnastics and it’s relevance to strength and conditioning. I know this concept is very “against the grain” for the majority of the gymnastics culture, and it is also very tough to dial in the logistics about how it would be possible given typical gymnastics training.

I think as the sport continues to grow and discuss how gymnasts should be training, we will see a movement towards this concept more and more. This may be a big factor in how we can build up strength to combat the forces of gymnastics that is a contributing factor for both overuse and traumatic injuries we see in the sport commonly like Achilles tears. Please note, I’m not advocating we run out and start weight training with all our gymnasts blindly or without proper investigation into the topic. This is simply food for thought that has a much larger application to just Achilles tears, and I’m hoping will be an area of discussions within the sport of gymnastics for the future.

Psychological and Fatigue Related Components

This could be a massive post series on its own, but as I often note the role of both physical and mental/stress always needs to be on coaches and gymnasts radar. With such complicated and highly involved skills/routines being done in gymnastics, thinking about the pro’s and con’s of pushing gymnasts during training is vital. Fatigue and stress have huge influences on both mental and physical performance, which athlete’s need to be firing on all cylinders for safety. If the gymnast is being pushed through these barriers without a regard they may be more inclined to land short, land wrong, loose mental focus for the skills technique, and not be confident in their skills which can all lead to many injuries one of which being Achilles damage. When coaches see signs of the gymnast’s focus and physical capacity falling apart, they need to be the one’s in control in regards to the athletes safety. Gymnasts also need to make sure to put their actual mental/physical state before their perceived mental/physical state that may be getting influenced by other factors to be in a small state of denial. It’s not always true that the last 1 or 2 floor passes while exhausted at the end of a workout are worth the possible outcomes. Again this is much broader to all injuries coaches and gymnasts need to be pro-active about, but I thought it was important to touch upon.

Training Environment, Equipment, and Mating:

There is a lot to be said about how crucial it is to maintain proper equipment and mating for gymnasts to land on. There is a lot of information published that discuss the need to help disperse forces through matting, and the need to make sure upkeep of this equipment is maintained. Although it can be expensive, overtime matting that has worn away looses it’s ability to cushion high impact landings. The proper matting and landing conditions must be paid attention to, in order to help reduce the forces and possible damage to gymnasts foot/ankle/Achilles over long training periods. Lots of information from experts in the field of biomechanics is available, and although it’s beyond this post to dive into it a lot I wanted to mention briefly. Readers interested in these more specific areas can definitely find a lot of good resources though USA Gymnastics website and continuing education area of the websites. There is also a huge conversation many people go into regarding the FIG code requirements and it’s influence on injury risks. That again is a huge topic of discussion that is much to lengthy to dive into here.

Putting It All Together

To sum up, think about the big picture when putting all of these things together for a gymnast. Before you read this list below, obviously this is not the case for every gymnast. I don’t want to make it seem like every gymnast is going to tear their Achilles, because that certainly is a little bit far fetched. It is simply an example to help people realize the possibility of a high risk for an Achilles rupture, and why I personally feel it is so important to stay ahead of issues like this with pre-hab techniques.

- Remember a gymnast may be taking forces 9x – 17x their body weight with every tumbling pass,

- Who may be taking a very high number of turns per day/week/month

- Who may have flat feet and looses shock absorption, which also causes almost double the force to go through the inside of the Achilles tendon,

- Who most likely has tight/shortened calf muscles getting pulled on forcefully during impact

- Who also may have very bad squatting and landing technique at baseline causing a lot of force to go through the ankle joint and Achilles

- Who may not possess the adequate strength and muscular/neuromuscular capacity to handle the forces of gymnastics

- Who may not be completely ready for the complicated tumbling skill or dismount at the end of their routine

- Who is in a very stressful, fatigued physical/mental state trying to perform during the middle of their competitive season

- Possibly landing on mats that have seen better days and aren’t ideal for landing

When you take a step back and think about some or many of these factors coming together, it may surprise many people involved in the sport. By no means do I have the perfect answer for how we can tackle an issue like this as a sport, but I think education and incorporating proper pre-hab/training safety techniques is good to being with. I’m sure there are many other viewpoints and ideas to think about. I am constantly learning from many other smart people working in the field discussing on topics like this, and I’m sure I will learn even more as the months go on. I think the risks and occurrence rates of Achilles tears in gymnastics is an example of how coaches, gymnasts, and medical professionals who have their hand in gymnastics need to work together to pro-actively stay ahead of serious issues like this. Major injuries like Achilles tears, ACL tears, lower back problems, and many more can be devastating for an athlete’s health and gymnastics careers. I hope this type of information has been helpful for readers and they can start to think about how we can address these issues in the sport. More on all of these concepts to come in the future. For now, best of luck

Dave

References:

- Clanton, TO. Return to Play in Athletes Following Ankle Injuries. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach. October 2012; 4 (6): 471 – 474

- Kader D , Saxena A , Movin T , et al . Achilles tendinopathy: some aspects of basic science and clinical management . Br J Sports Med . 2002 ; 36 : 239 – 249 .

- Martin RL, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Ankle Stability and Movement Coordination Impairments: Ankle Ligament Sprains. JOSPT. September 2013; 43(9) A2 – A40

- Wertz, et al. Achilles Tendon Rupture: Risk Assessment for Aerial and Ground Athletes. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Sept/Oct 2013; 5 (5): 407 – 416

- Caine D., et al. The Handbook of Sports Medicine In Gymnastics. First Edition. John Wiley and Sons, 2013

- Bradshaw E.J., Hume P.A. Biomechanical approaches to identify and quantify injury mechanisms and risk factors in women’s artistic gymnastics. Sports Biomechanics. 2012; 11(3) 324 – 341

- DeLee JC , Drez D , Miller MD . Achilles tendon injuries . In: Orthopaedic. Sports Medicine: Principles and Practice . 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA : Saunders Elsevier ; 2010 : 2182 – 2205 .

- de Vries JS., Krips R., Blankevoort L., van Dijk CN. Interventions For Treating Chronic Ankle Instability: A Systematic Review. The Cochrane Library; 2011 (8)

- Chilvers M, Donahue M, Nassar L, Manoli A. “Foot and Ankle Injuries in Elite Female Gymnasts”. Foot & Ankle International, Vol 28, No.2, Pages 214-218, Feb, 2007.

- Peak Performance: The Research Newsletter on Stamina, Strength and Fitness. Achilles Tendonitis: Prevention & Treatment. 2004; Peak Performance Publishing, Goswell Road, London.

- Smith-Young, B. – “How To Avoid Achilles Tendon Rupture” (http://www.gymmomentum.com/uncategorized/how-to-avoid-tendon-rupture/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A%20GymMomentum%20%28Gym%20Momentum%29&utm_content=Google%20Reader)

- Gymnast Care Podcast – Dr. Josh Eldrdige and Dr. Bill Sands (http://gymnastcare.com/dr-bill-sands-transcript-of-podcast-interview)