How A Gymnasts “Tight Hamstrings” May Really be A Core Control Problem

Something really interesting happened to me the other night at the gym during practice, and I wanted to share the story. One of my level 8’s told me that she has “really tight hamstrings” and that for some reason no matter how much she stretches her splits or pikes they never get better. I know this gymnast personally, and I know that she is one of the most flexible/hyper mobile girls on our team. So naturally I was thinking there had to be more to this. I decided to take a few minutes to break it down and figure out if it was really a hamstring mobility problem based on a lot of the PT information I’ve been reading/listening to lately. What ended up looking light tight hamstrings and a restricted pike stretch was really a core control /stability problem, and by doing some corrective work I was able to fix what looked like tight hamstrings in about 5 minutes.

Before I dive in, if you want to get a full free gymnastics flexibility guide, be sure to download my “10 Minute Gymnastics Flexibility Circuits”

Download My New Free

10 Minute Gymnastics Flexibility Circuits

- 4 full hip and shoulder circuits in PDF

- Front splits, straddle splits, handstands and pommel horse/parallel bar flexibility

- Downloadable checklists to use at practice

- Exercise videos for every drill included

As a very important note to start for readers, not all gymnasts need more mobility and more stretching. In fact, many issues are due to too much mobility, and the gymnastics not having enough stability/control to handle the excessive motion. This is a case just a demonstrate a point, but you should know that this gymnast is way on the hypermobile side of things, and I make her spend quite a bit of time on control work. Any way, It all started out with her showing me a pike stretch, where she said she felt a lot of pulling in the back of her legs because of her hamstrings and she could not reach her hands to the floor.

You may notice she has a non uniform curve in her lower back (it’s pretty flat), and she also has an increased upper back rounding as a compensation. This can come about as the gymnast has lacking core control, some hip issues, and also tends to depend on their lower back to extend with skills. This all can lead up to increased arch back as a compensation , create mobility issues as a secondary problem, and then she will be missing good forward motion. This is an issue that is being worked on too. However, for the sake of the post, I just wanted to illustrate the core control/”tight hamstring” situation.

Here is how the rest of the process went down. The first thing I did was look at her hamstring flexibility with a passive straight leg test. This is commonly how gymnasts stretch their hamstrings with a partner. The gymnast lays on their back, straightens their knee as much as they can, brings their toes up toward their head while making sure the other leg stays on the ground. I had a coach brings their leg up as far as it will go until she felt a stretch in the hamstrings, to really see what her flexibility was. Here is what it looked like

I then had her stand up and do a pike stretch with one leg up on a block, slowly reaching down, to look at the pike with each side working one at a time.

When offloaded and reaching slowly down to one side, she was able to touch the floor easily with no reports of pulling in her hamstrings. Clearly from these pictures above, she seems to have some good hamstring flexibility available. Then, to see if it was a problem related to her reflexive core/spine engagement, I had her lay back down to do a straight leg raise the same way, but on her own. This looks to see if the gymnast can first stabilize their core and spine before they raise their leg. Here is what this looked like.

From looking at the passive motion (hamstring mobility) to the active motion (core stabilization with lifting leg pattern), there is a pretty large difference between the two. This suggests that the core is really the problem, and not “tight hamstrings”. During the pike stretch to the floor and the active straight leg test above, the brain is not firing in good sequence to set the core THEN move into the motion. This gymnast simply kept their core in the arch back posture or anterior pelvic tilt she chronically has problems with. This actually causes the hamstrings to go on more stretch as well due to them attaching on the bottom of the pelvis bone. Due to the core/spine not having good reflexive or automatic core stabilization, the brain subconsciously puts a stop to how far the leg will go or how far the pike stretch will go because it is trying to protect the back.

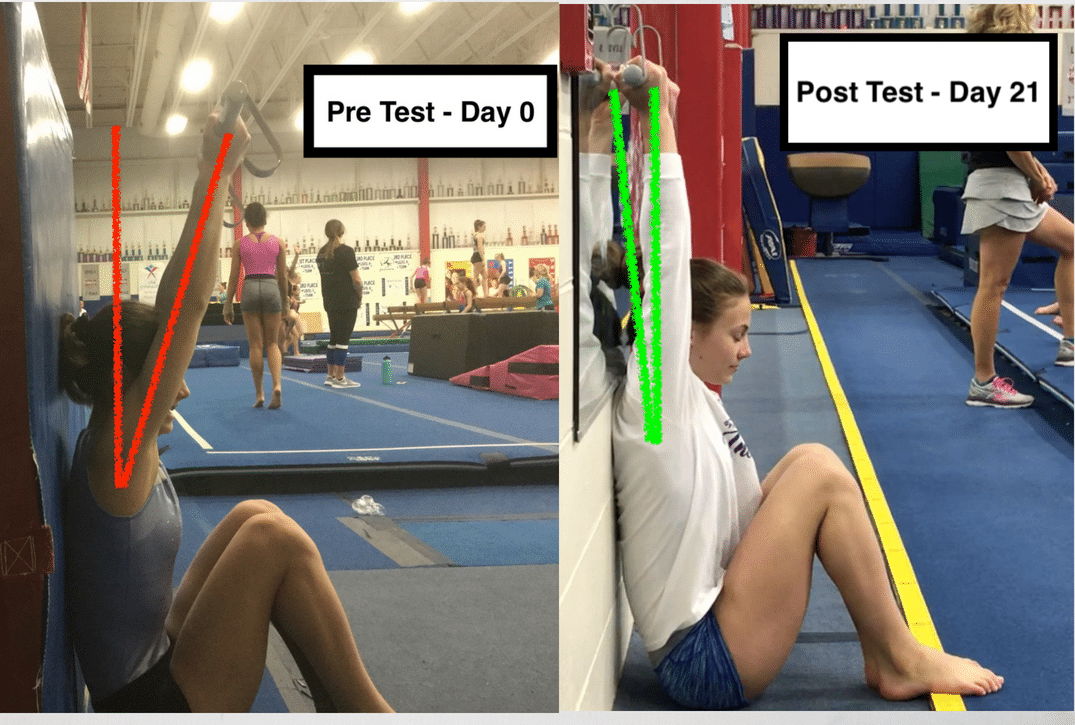

So to keep looking at the problem, I had the gymnast do a drill that looks at what the legs can do when the core is properly engaged. To do this I asked a coach put her arm up, and then had the gymnast push down into it. This motion engages the core musculature. I then asked the gymnast to raise her legs again, and you might be amazed at what the difference was.

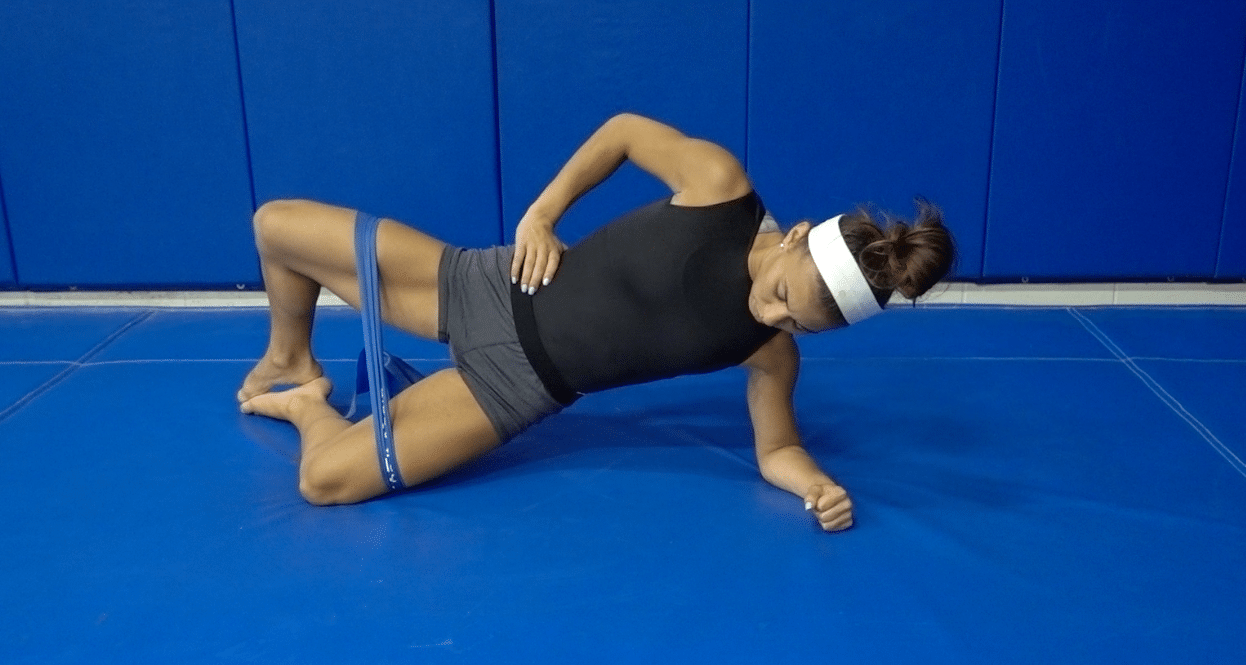

Although it was not as much as her passive hamstring testing, there was a huge difference in how far she could raise her leg up. This further points to the fact that this is not a hamstring mobility problem, this is a core stability problem. So, based off of a lot of literature I have been reading, the authors of these texts suggest that you should look at the way some one rolls to identify if the person is having a problem activating the core musculature. These are called developmental rolling patterns, and although they require some specialty education to learn about I had her do some of these along with the drill above to look at/work on her core engagement.

You would be amazed at how challenging some of these were for this gymnast. There were patterns she simply did not know how to do, and it looked as if she was “stuck” during some of the upper body ones. This is where things got really cool. After 5 minutes of rolling and basic core stability work like the drill above when she pushed down into the coaches arms, I had her stand up and re-test her pike stretch. Lone behold, this is what it looked like.

Why This Matters

The reason that I posted this story and wanted to tell people about it definitely isn’t to confuse or show some wild type of PT work. The reason I want to show this is because it is a perfect example of the difference between a mobility (hamstrings being “tight”) and a stability (core not reflexive stabilizing) problem. Basic core stability and core control is a huge issue in gymnastics, and although gymnasts have strong muscles they often times don’t know how to use them during practice and skill work. This a concept Dr. Josh Eldridge harps on with his website, and this is an example of it coming into play. I heard a really cool analogy when listening to a podcast from Dr. Dan Pope’s website. They said that it is like trying to fire a big powerful cannon off a boat in the middle of a lake. It doesn’t matter how strong the cannon (arms, legs, muscle etc.) is, because the cannon is on an unstable base of water (like not having proper core control and core stabilization reflexively). We have to put the cannon on a stable surface like the ground to really see the cannons potential. This translates to first developing a strong basic core for all motions, then working on building strength and power on top of this.

Unfortunately, I think many coaches would see this gymnast doing a pike stretch and assuming they have “tight hamstrings” and start hammering away on her flexibility. This can be an explanation to someone getting confused as to why no matter how much they stretch or do flexibility it doesn’t get better. Doing ton’s of flexibility for this gymnast isn’t going to help, and actually it may make it worse. The hamstrings attach at the bottom of the pelvis the more lengthened they get, the more a gymnast is allowed to move into the arch back or anterior tilt that so many gymnasts have. For an athlete like this, the hamstring muscles may be turned on excessively by the brain (up regulated/facilitated) to protect the lower back from falling more into the arch back posture or anterior pelvic tilt many gymnasts express. This is a very dangerous position for their lower back, can lead to overuse injuries, increases the risk of traumatic jarring of the back because the back rests in this posture, is decreasing their core engagement capabilities, and most likely is affecting their gymnastics skill work. Today I did the same type of work with some of the other girls out of curiosity and found a lot of the same problem.

Now, I’m not saying that everyone should make their girls lay on the floor rolling back and forth to try and get their pike and core better. Also, there are definitely times when hamstring mobility is limited in an athlete, and it does simply come down to doing more mobility work (although simply stretching someone to their limit may not be the only way). This is not always the simple fix, there are other theories that authors talk about. These are related to joint centralization (this hip joint not sitting in an ideal position), other lower back and pelvis joints, and nerves/muscles deep in the hip that may also be a factor. This process is something that takes an educated/trained eye to pick up and when done on a whim by someone without the training can cause a problem. This is a time when a gymnast needs the help of a trained medical professional who understands these problems in depth and knows how the system works based on mobility/stability, and so on.

This post is simply to get people to think about some of the issues we are seeing in gymnastics related to injury and decreased skill performance. This concept has parallels to a lot of other issues that may be going on in gymnastics. I actually applied the same concept to someone who had very “tight shoulders” despite stretching all the time, and found similar results. Once I become more familiar with that process of evaluation I will post what I found in another article. I think there is a huge amount of work to be done in discussing the issues we see in gymnasts, and maybe that we need to start integrating these concepts regarding why gymnasts have some common issues in our gymnastics practices. I by no means have the answers to all of the problems, and I am definitely not an expert at this type of work just yet. However, I think this story serves as the perfect catalyst to opening the door to some of these schools of thought. I hope everyone found this as cool as I did. That’s all for now,

Dave

References

- Cook G., et al. Movement – Functional Movement Systems: Screening, Assessment, Corrective Strategies. First Edition. On Target Publications, 2010.

- Dr. Perry Nickelston, DC, FMS, SFMA – www.stopchasingpain.com

- Dr. Dan Pope PT, DPT – www.fitnesspainfree.com