Avoiding Pre Season Pit Falls In Gymnastics: 5 Training Concepts We All Must Consider

For almost all gymnastics programs, the summer training cycle has finished and teams are now moving towards pre-season. In order to maximize performance and reduce the risk of injuries over the entire competitive year, gyms must approach this 3-4 month period with a well thought out plan. To help readers out, I wanted to share some of ideas of mine based on research I have been reading, the pattern of injuries I saw last year in preseason, and some information I have been very thankful to learn from higher level coaches within USA Gymnastics. As a heads up, this post does have some more technical terms / jargon from the Strength and Conditioning Field. People may find it helpful to invest time reading some strength and conditioning books to help solidify these ideas.

Table of Contents

1. Caution Too Much or Too Little In Training

Recently I have been studying some really great work in the areas of optimal training load and athlete adaptation in relation to performance enhancement. This Olympic Position Statement on Load In Sport (find Part 1 and Part 2 here), as well as this great paper by Tim Gabbett from the British Journal of Sports Medicine outline how crucial it is to apply the appropriate level of training load to athletes gradually. This is in an effort to foster positive adaptation, trend towards increased performance over time, and reduce the risk of injury / overtraining.

One of the major overlapping factors to all overuse injuries I’ve treated with gymnasts is the inappropriate application training loads. This applies to too much, too little, or too sudden of an increase at one time during practice to prepare for meet season. Although unfortunately sometimes athlete or coach ego contributes to a drastic increase in loading (hard for the sake of being hard), for the most part I think it’s simply a lack of education or not having a formal plan in place. More on that below.

As some epidemiological research in Gymnastics Sports Medicine Handbook outlines, “injury rates can increase following periods of decreased training, during periods of practice of competitive routines, and during weeks just prior to and during competition” (Chapter 10 Epidemiology of Injury in Gymnastics). I think that the research concepts from BJSM on training load have huge implications for gymnastics. We can’t just dive into the start of the season with our foot on the gas pedal, a mistake I made all too commonly as a younger coach. We want to maintain an appropriate level of intensity increase to push our athletes, but not so much that they are overloaded and starting off season with 75% of their fuel in the tank.

2. Have a Well Thought Out Plan in Place

Both overloading and under-loading of athletes may be problematic for injury occurrence as well as not reaching high levels of performance. Remember, it is not only appropriate but important that we push our athletes hard in training. Appropriate and safe training followed by recovery helps build athlete capacity, increase tissue resiliency, and improve overall levels of physical/mental preparedness. This goes for actual gymnastics skills or routines, strength, mental training, metabolic systems, and more. However, this is not an excuse to crush our gymnasts day after day without a well thought out plan or scientific rationale behind our training methods in place.

Take for example building general metabolic capacity as routines approach. One of the biggest errors I see in pre season is that we don’t prepare an athlete specific metabolic system (PCr and anaerobic glycolytic) on a general level before we ask them to do gymnastics specific metabolic work in routines. We want to prepare our athletes and build fatigue resilience with lower risk modalities first before taxing our athletes in gymnastics specific, higher risk, fashions of routine work. This not only sets them up for success, but also reduces the very common situation of fatigue influenced injuries.

There are many other applications of these concepts, but it all comes down to the plan. The plan must consider

- individual skills progressing to routines (how many individual skills, 1/2 routines, or full routines will be performed per day/week)

- strength programs progressing to power or more metabolic based focuses

- alternating training intensity through heavy/medium/light/complete rest days to promote proper adaptation

- considering total hours and days of training, and recovery – adaptation time periods.

- how many weeks until the first meet, how many days per week or hours per week of training occur

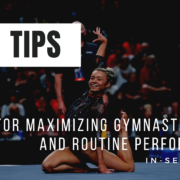

As an example, this small screenshot from my global template of periodization and the competition year that guides our preseason map.

There will obviously be flexibility within this based on the athlete response and the realities of training in a crowded gym. But, having this in place allows you to reverse engineer each training week and practice to stay on track, while not overloading or under-loading our athletes. We must also factor in the reality that other components of our athletes lives directly affect gymnastics training (school, social life, sleep, nutrition, hydration, etc). Not considering these concepts can make both performance and injury rates suffer before season gets started.

3. In It For The Long Haul

The competitive season in gymnastics is long, taxing, and has many points where athletes can face problems. With the first few months of competing will come inevitable soreness, fatigue, stress levels, and the anxiety of competition. This is a normal part of any sport, and is why considering the entire season is so important. It’s great to do amazing at the first few meets of the season, but I personally don’t feel it’s justified if half the team is burnt out and injured crawling into states, regionals, easterns/westerns, nationals, or elite meets. As coaches and medical providers, we have to play our cards right to make sure we have an intelligent and proactive approach for the entire year.

A really important concept to consider from the research above is the acute to chronic work load ratio. Tim Gabbett outlines that the acute load can be considered one total week of training volume, and how much/how intense it is. The chronic work load can be considered the average work over a month of training. The research suggests that when the acute load (one week) drastically increases above the chronic work load (4 week average), it may be a concern for performance drops and injury risk.

In gymnastics terms, this means that you can’t expect a gymnast to come back from summer starting with working skills, then within 2 weeks expect them to perform full routines or compete on hard landings. Intuitively many people understand this make sense, but I see it all too commonly coaches become panicked that athletes are not read for competition and drastically increase training or individual skill intensity. It’s okay to start off slow and build to a larger peak in the middle of the season. Turning the dial up on routines, strength, and metabolic work all at once without a plan can create problems fast. I urge readers to be smart about this, and be sure to infuse it within preseason training.

4. Recovery Time is Where The Magic Happens

As I hope readers can understand, I’m all for intelligently designed hard training that helps athletes prepare to for success during competition season. Strength programs, metabolic work, and routine preparation needs to be challenging to foster adaptation and readiness. Athletes must understand the reason behind the hard training, and coaches must be appropriate in pushing the athletes intelligently. With this in mind, coaches and medical providers have to understand basic principles around recovery, adaptation, and stress response. Contrary to popular belief, adaptation doesn’t occur during times of hard intensity and effort. Adaptation occurs when the recovery time period and recovery environment is available. This is often as an ongoing dynamic process in response to stress as the body attempts to regain homeostasis (a concept known as allostasis).

On one side of the coin, proper recovery – adaptation from training comes back to varying practice intensity within a periodized model. Without planning periods of lighter training load or complete rest, adaptation will not occur and the athlete will have a progressive downward spiral for performance as workloads cumulate, fatigue levels increase, overtraining occurs, and injuries snowball.

On the other side of the coin, there is a lot of this that is the athlete’s responsibility. Understanding the importance of sleep, nutrition, hydration, soft tissue care, and balancing other external life stressors like schoolwork is paramount. Education to the athlete can come from all parties involved, but actual execution of these ideas is up to them. The pre season is a great time to get these ideas culturally in place.

One of the leading experts in this field is Dr. Bill Sands, and I highly encourage everyone take the time to give this brand new Gymnast Care Podcast a listen where he discusses recovery, optimal loads in training, flexibility concepts, and more with my friend Dr. Josh Eldridge. I also suggest that people check out this fantastic strength and conditioning book that has a recovery chapter from Dr. Sands as well.

5. The Importance of Monitoring Athlete Response To Training

Understanding how athletes respond to training and the preseason allows a coach to be realistic about planning each week. Authors with the BJSM review article outlined how both the external load (hours of training, number of skills/routines performed) and the internal load ( individual physiological and psychological responses to training) must be considered.

The external loads can be tracked as noted above, through planning and counting of actual training loads. Other measures of subjective athlete report can be very helpful for internal load monitoring. Some basic sheets such as rate of perceived exertion (RPE), self reported fatigue or soreness levels, hours of sleep, and resting heart rate are just a few. These tracking concepts help both the athletes that may be over reaching (many levels of soreness, fatigue, elevated resting HR) or under reaching (not sore/fatigued after heavy strength or routine day). Along with attendance and growth rates, I have the athletes I work with track these basic markers daily for me to keep tabs on. For those with teams and longer term goals, I strongly suggest the do the same.

I know there may be a lot of information within this article, but I think these concepts need to be applied better in gymnastics training. I hope that everyone got a few idea sparks and can find ways to start some small steps to changing their training. Best of luck!

– Dave Tilley DPT, SCS

References

- Soligard T, Schwellnus M, Alonso J-M, et al. How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:1030–1041.

- Schwellnus M, Soligard T, Alonso J-M, et al. How much is too much? (Part 2) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of illness. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:1043–1052

- : Gabbett TJ. The training-injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder? Br J Sports Med doi:10.1136/ bjsports-2015-095788

- Caine D., Russell K., Lim L. Handbook of Sports Medicine and Science, Gymnastics. October 2013, Wiley-Blackwell

- Joyce, D. Lewindon D. Sports Injury Prevention and Rehabilitation: Integrating Medicine and Science for Performance Solutions: 1st Edition. Routledge 2016