Combatting Elbow OCD Injuries in Gymnasts

Many gymnasts deal with an injury known as elbow OCD, or osteochondritis dessicans. This repetitive overuse injury to the cartilage of the elbow joint is sadly becoming much more prevalent in young gymnasts, causing many months of missed practice and significant quality-of-life declines. In the worst of situations, it can cause gymnasts to prematurely stop gymnastics at a young age in fear of long-term health outcomes.

Being a Sports PT who works with a lot of gymnasts, I’ve sadly treated hundreds of gymnasts for elbow OCD in my career. There is a lot of confusion out there for parents, gymnastics coaches, and gymnasts about what is going on and what to do. So, in this short blog, I’d like to overview the basics of elbow OCD, why it occurs, what treatment options are, and how gymnasts can safely do rehab and then get back to gymnastics.

Before we dive in, if you are a Gymnastics Medical Provider or Coach who wants to learn about the most common injuries, how to treat them, and how to help prevent the from occuring, be sure to sign up for our 2023 SHIFT Symposium where we will cover this in depth on Day 1.

It is also CEU approved for PTs and ATs to claim credits and has 7 hours of incredible lectures that you will have lifetime access to.

That said, lets dive in!

Table of Contents

What is Osteochondritis Dessicans?

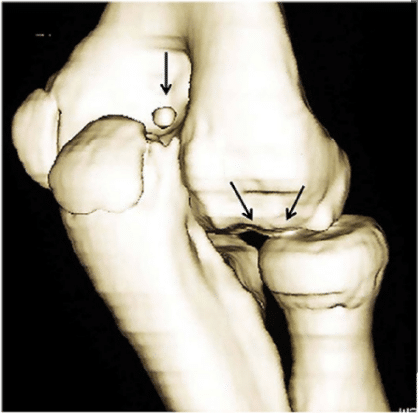

Simply put, OCD is a repetitive overuse injury to the cartilage of the upper elbow joint bone. For reasons I will share next, the cartilage that is not fully mature begins to get inflammation and damage. For some, it is very mild and only results in this irritation as well as pain. With rest and proper care, it can quickly be dealt with. These are also referred to as Grade I or II, small, and stable lesions

Other gymnasts, unfortunately, continue to train through bouts of pain and develop much more serious damage to the cartilage. The surface of the cartilage can begin to crack, and the underlying bone beneath the cartilage starts to become damaged. This is where things get much more concerning, as you can not grow back the native cartilage and pieces of bone or cartilage might start to break off and float in the elbow joint. This can lead to more damage in the joint but also really big movement limitations and pain. These are referred to III, IV, or V, large, and unstable lesions.

How Does OCD Affect Gymnasts?

Gymnasts are at a higher risk for developing OCD because of the repetitive motions and high-impact landings involved in the sport. These motions can put stress on the joints, leading to small fractures or chips in the bone. If left untreated, these fractures can lead to OCD.

Symptoms of OCD in gymnasts include pain, swelling, and stiffness in the affected joint. In some cases, a gymnast may hear a snapping or popping sound when the joint is moved. If the detached piece of bone and cartilage is large enough, it may become lodged in the joint, leading to further pain and limited range of motion.

What are the Warning Signs of OCD in gymnasts?

Typically the earliest warning sign of elbow OCD is pain on the outside of the elbow, and stiffness. Many gymnasts may think its simply an overuse elbow tendons injury like lateral epicondylitis or golfers elbow.

While sometimes that can be true, OCD lesions tend to be much more sore, achy, and feel deeper. They also tend to hurt with passive ranges of motion, whereas epicondylitis hurts more with gripping and active use of the forearm muscles. Ligament injuries tend to happen with trauma or a fall.

So if you are suspicious of pain that has been going on for multiple weeks, is present with weight bearing like cast handstands, and creates noticeable deep aching, it might be worth rest and getting checked out.

How Do We Treat Elbow OCD?

If someone is concerned about elbow OCD, they will often go to a doctor or elbow specialist for assessment. If there is worry about OCD an xray, MRI, or CT scan might be used to specifically look at the cartilage health and integrity. From here, combined with a physical examination, a diagnosis of elbow OCD, as well as a grade (I-V) and stable vs unstable, can be made. Often times the size of the OCD lesion will also attempt to be made.

Citation – https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1947603519847735

From here, there are two main paths forward.

Nonsurgical Treatments For Gymnasts With Elbow OCD

For smaller, stage I-II, stable lesions, usually the first course of action is rest and physical therapy. Due to the significant nature of elbow OCD surgery (more below), we want to avoid it at all costs if we can. Remember that the inherent cartilage within the elbow joint is never the same once we disrupt things.

So, doctors will often recommend that gymnasts completely rest from upper body impact for 3-6 months in an attempt to let the elbow hear. This is often devastating for gymnasts, coaches, and parents to hear. Unfortunately, it truly is the best path forward. It’s not that a gymnast can’t continue to do leg strength, core strength, flexibility, and other things in the gym safely. But, we really do want to attempt full rest from elbow impacts and hanging as that overuse was what created the cartilage to become damaged and start to degrade in the first place. While 6 months does seem a long time if in exchange a gymnast can avoid surgery or possibly having to quit the spot from a massive cartilage injury, that clearly is the better option.

I work with many gymnasts in this phase and go out of my way to make a very elaborate plan of all the things they still can do. They are often doing 2-3 days per week of lifting for their legs, core, and another arm as well as safe flexibility, cardio, and prehab circuits.

In 6 months’ time, they often will re-examine the elbow with an X-ray, MRI, or CT scan as well as do an assessment of pain levels. If pain levels have subsided, and the imaging looks good, gymnasts can start a slow re-entry into gymnastics. I will cover my thoughts on how do this further below in this blog to give people guidance.

Sadly, not everyone gets better with rest. Or, sometimes someone has a larger, unstable, Grade III-V elbow OCD lesion that is not amenable with rest alone. That is where surgery comes in.

Surgical treatments for gymnasts with elbow OCD

There is a range of surgical options for elbow OCD, ranging from less invasive to more invasive. I don’t want to go super nerd mode here, so below I will make a list moving from this least to the most invasive. They generally are in the 3 categories of debridement, microfracture or drilling, and cartilage replacement.

-

Debridement

- In this surgery, there isn’t a ton being done to the actual OCD lesion. They oftentimes will simply go into the elbow joint, clean up the irritated and damaged cartilage tissue, and remove and lose bodies or aggravated tissue. For less severe cases, sometimes this can be useful particularly if bone fragments are the main issue. But, in many cases who have gotten to the surgical step, more might need to be done to promote healing in the elbow OCD lesion.

-

Microfractures/Retrograde Drilling

- This surgery involves actually doing work on the elbow OCD lesion itself. With both of these procedures, small holes are intentionally made in the area of cartilage that is damaged and injured. Doing this promotes new healthy blood flow to the area and also stimulates the growth of new cells to the area. The intent of this surgery is that by doing this, the body can help lay down the new bone that isn’t the original but is able to protect the area.

-

Cartilage Replacement (Mosiacplasty and OATS)

- This is the most common type of surgery being down for most gymnasts. with OCD lesions. It’s certainly more of what I see in the clinic month to month. In these procedures, instead of simply picking at the blood to promote healing, the aim is to fully replace the missing area of cartilage. Both of these procedures often involve using another area of the body that has a similar type of cartilage, the knee. In a mosaicplasty, many smaller fragments are taken and put into the elbow OCD lesion to create a small puzzle-like fill-in appearance. In an OATS procedure, one large bone plug is taken from the knee and put into the OCD lesion. While there are a variety of research studies on the outcomes, it seems that OATS procedures are taking the lead on really good long-term outcomes for gymnasts in terms of pain, function, and getting back to gymnastics safely.

How long is the recovery for gymnasts who have an elbow OCD take injury?

As covered above, for those on the non-surgery path it’s about 3-6 months of rest minimum to allow for healing. If they are able to see progress, there is usually a 4-6 week slow introduction back to gymnastics. I typically see this taking anywhere from the 4.5 to 8-month range depending on how things go.

A lot depends on the size and severity of the elbow OCD lesion, the age, and level of the gymnast, their goals, and so on. This is so that a gymnast can regain their strength, flexibility, and upper body load tolerance. I will cover this in-depth in the last section below.

For those that do have surgery, there is a much more structured timeline for the progression of healing.

Rehabilitation for gymnasts with elbow OCD surgery

I tell gymnasts that there are 4 phases of elbow OCD rehabilitation, usually roughly taking 6-8 weeks.

-

Phase 1 or “Put The Fire Out”

In this phase, it’s all about just protecting the elbow and getting it to calm down. A gymnast is usually put in a brace at 90 degrees for 1 week, and then slowly the brace is unlocked as they start PT to get their range of motion back. The keys to this phase are reducing swelling, reducing pain, getting a range of motion back slowly, reversing strength losses, and just letting things calm down. PTs typically focus on soft tissue care, modalities for muscle relaxation, hands-on range of motion, and basic exercises. Depending on the surgery and patient, this can take up to 8 weeks. It is crucial that the gymnast not put any weight on their arm, or lift heavy items, to protect the OATS graft

-

Phase 2 or “Be a Human Again”

Following the first few months up to 8 weeks, usually passive range of motion is fully back and the active range of motion is close behind. During this phase, light wrist dumbbell exercises, active range of motion of the shoulder, and basic bicep curl/tricep extensions may start with light weights. We really want to use this time to improve shoulder flexibility and wrist flexibility, as those will be key for getting back to gymnastics and de-loading the elbow. Also, lots of attention should be paid to increasing shoulder strength for this reason as well. This also takes about 6-8 weeks, taking someone up to the 3-4 month mark when all said and done.

-

Phase 3 or “Be an Athlete Again”

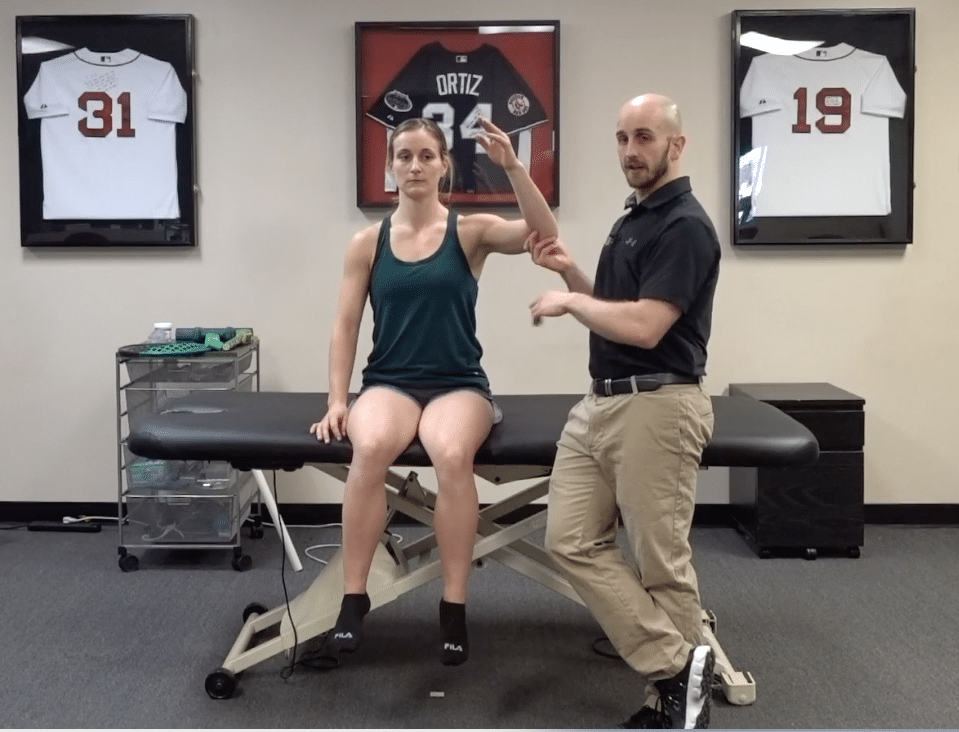

This is a phase that is one of the most critical, but I often see overlooked or a little underdone. A gymnast must regain full advanced strength, power, and speed use of their arm before we start the most basic gymnastics progression. First is the return to weight bearing on the elbow. Typically at 3-4 months, surgeons will re-image the arm and make sure the OATS graft is fully healed, and that the pain levels are low. If this occurs, over 4 weeks I like to slowly progress back to upper body weight bearing. I like to start with hands and knees rocking on dumbbells, then progress every few days. The next progressions are bird dogs, hands and knees rocking on flat hands, bear crawls, and then tall plank shoulder taps. In the later stages, tuck handstand holds on a box, then pikes, then wall handstands.

It’s also crucial that single-arm strength is rebuilt here. I first start with exercises like dumbbell floor presses, bent-over dumbbell rows, 1/2 kneeling overhead dumbbell presses or landmine presses, and 1/2 kneeling cable pull-downs. I also add a lot of shoulder work for the rotator cuff and scapula like side-lying dumbell ER, prone T, prone Y, prone U, and standing full cans. We then eventually progress to box push-ups, pull-ups, feet-elevated rows, and tuck handstand push-ups.

-

Phase 4 of “Be a Gymnast Again”

This is the actual return to gymnastics phase, which typically starts around 6 or 7 months once a gymnast has been fully cleared by their surgeon. I will finish up the blog with this.

How to Safely Return to Gymnastics After Elbow OCD

This can be one of the most intimidating things for gymnasts, coaches, and medical providers. If you do not have a good working knowledge of the sport, sometimes safely getting back can feel daunting. For me, I create a 6-week return to sport plan that loads the elbow every other day. By going every other day, we have a 24-hour window to monitor symptoms and make sure no pain comes up. While some soreness is to be expected after 6-7 months away, it should not last more than 24 hours. I make programs that progress every week based on

-

Surface

I start gymnasts on soft surfaces, like Tumbl Trak and trampoline. After two weeks, we progress to a mixture of rod floor for more basic skills and keep on with trampoline for harder skills. Then in the final two weeks, we go back to the hard floor with a sting mat for basic skills and keep on a rod strip for harder skills.

-

Repetitions

This one is intuitive, but we want to slowly add more repetitions over time and avoid suddenly doing too many. The first two weeks, I tend to put skill reps in the 3-5 range, and then the next two weeks in the 5-7 range, and then the last two weeks 7 for all as a skill cap.

-

Skill Difficulty

This can be tough if you did not do gymnastics or do not coach gymnastics, but in my experience talking with coaches, gymnasts, parents, and medical providers as a group helps create a solid plan. Based on the gymnast’s age, skill level, and goals, we start with the basics first and then progress to harder skills. The first two weeks might have only basics and single skills, whereas the middle two weeks might have connected skills and parts, and the last two weeks might have the hardest skill a gymnast does. We can also progress from single skills to combinations of skills, to half and full routines over the 6 weeks if things are going well.

Can We Prevent Elbow OCD In Gymnasts?

This is quite a large, complex area to discuss, but the short answer is yes and no. Yes that we can likely reduce risk, but no that we are able to completley prevent all OCD injuries. That there are many factors. The most common thing I tend to hear from coaches or parents about what causes elbow OCD in gymnasts are 1. Genetics and 2. Technique.

While these might be small factors, and I don’t want to dismiss them, in my opinion, I do not think these are the biggest reasons why we are seeing such a large increase in elbow OCD in gymnasts, and how to reduce risk. In my opinion, the largest contributing factors in order of importance are

-

Elbows are Not Knees

Elbows do not have the same inherent weight-bearing cartilage or surfaces that a knee does like a meniscus or large weight-bearing tibia. For this reason, elbow joints are simply more at risk and gymnastics is very unique in having gymnasts use their arms like legs.

-

High Forces on Young Kids

Not a popular thing to say. But, the reality is that gymnastics has gymnasts doing skills with 2,3, an 4x body weight at very young ages at 10-14 years old. Sometimes gymnasts are training level 8, 9, 10, or elite skills in this age bracket with massive forces. The sport has only gotten harder in the last 20 years, with younger and younger kids training in advanced skills.

-

High Training Hours and Repetitions

Again, probably not what people want to hear but it’s reality. If you look at gymnastics practices, these same gymnasts can be doing 100-200+ upper body elbow impacts per session. Add those numbers up weeks to months, and we are in the 1000s easily.

Even crazier, sometimes there is zero guidance or regulation around how many hours a young gymnast can train. I’m a huge fan that quality and quantity matter, i.e. that gymnasts can do 15-20 hours safely when they have great coaching and structure at a young age. But, this can quickly become a runaway train. I’ve heard of some gyms having 8-year-olds train 20+ hours per week (yes you read that right) and 10 – 12-year-olds being homeschooled and training 30 hours per week. This is insanity in my mind.

I know many great, world-class coaches who have produced world and Olympic medalists who got along just fine with younger gymnasts training 15 hours per week, and then doing 20 through middle school, only getting to 20+ once they were through puberty and fully developed. We need guidance and regulation on training hours in young gymnasts.

-

Year Round Training

If you look at the research about year-round training (aka training more than 9 months per year in a single sport) you can see that it significantly elevates the risk of overuse injuries in young child athletes. This is even more so in the elbow as is seen in baseball. Gymnasts not having a relative off-season, and in some cases, gymnasts literally only have 7-14 days off total per year, which is nuts. The research is clear that having a relative off-season would reduce the risk of elbow injuries like elbow OCD.

-

Early Specialization

In line with this, many gymnasts specialize and only do gymnastics at the incredibly young age of 5, 6, or 7 years old. I’m all for gymnasts being on the earlier side of this curve, as the sport is very hard and some gymnasts have really high-level goals. But, I think only doing one sport starting at age 5 is undermining their athletic potential and set them up for elevated overuse injury risk or burnout like the research suggests. Up until 10, I love for gymnasts to try a variety of sports. Other sports that spare the elbow and impact like swimming can be really useful here.

-

Lack of Weight Training/Hybrid Strength Models

This is a big one for me. The research is clear that hybrid models of strength training that use both external weights and body weight gymnastics type work is good. In gymnastics, the culture still largely has not adopted weight training for young gymnasts, and I think issues like elbow OCD and other overuse injuries are a big area this could help. External weight training helps to slowly expose the non-weight-bearing elbow to forces to increase its capacity,y but also built up muscular strength around the area and above in the shoulder to buffer forces.

-

Lack of Workload Monitoring

Plainly out, if we don’t keep a record of how many upper body impacts we are doing, things can get out of hand quickly. Gymnasts often have multiple events where they are loading their elbows over and over between vault, floor, beam, pommel horse, bars, and more. We have to be aware of this and keep loose guidelines for repetitions as well as rotate when they do hard impact.

-

Technique

There is research to suggest that certain types of round-offs and backhand springs, where the hands are turned very wide out and the elbows are locked, might be more concerning for elbow force loading. Instead, slightly rotated in hands or straight ahead hands during back handsprings, and “T” position round offs, might be a better alternative.

-

Genetics

As I mentioned, genetics does play a role. There are certainly some situations where someone is more at risk based on their cartilage and boney profile, or possible the body dimensions they have.

I don’t say all these things to scare people out of doing gymnastics. I love the sport, know there are amazing coaches out there training kids to do these skills well, and that there are many ways to stay ahead of the risk curve. But, in order to help change or fix something you have to look at the problem head-on and accept reality.

My opinion is that until we address cultural and systematic issues around high repetitions, very young gymnasts training competing for hard skills before puberty, year-round training, early specialization, lack use of weight training, and cultural issues around training workload or lacking periodization, we are going to be fighting an uphill battle. Yes, technique and genetics matter. Yes, the injury might still occur. But I feel like there is a lot of low-hanging fruit here that we have yet to really address and move the needle on.

Concluding Thoughts

So, it is definitely a lot to think about with elbow OCD in gymnastics. While we still have a lot more work to do on the research and training side, there are some great strides being made. Hopefully, this was a good summary of where we are at and can provide some answers for those who are confused or overwhelmed by elbow OCD.

Keep in mind, if you are a gymnastics medical provider I will be giving a full, in-depth lecture on exactly how I treat and rehabilitate gymnasts who have elbow OCD lesions.

Again, ifyou are a medical provider working with gymnasts or just a coach who wants to learn about this, you definitely do not want ot miss out on this day jam-packed full of gymnastics medical lectures. hope to see you there!

– Dave

CEO/Founder of SHIFT

References

Kajiyama S, Muroi S, Sugaya H, Takahashi N, Matsuki K, Kawai N, Osaki M. Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Humeral Capitellum in Young Athletes: Comparison Between Baseball Players and Gymnasts. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017 Mar 1;5(3):2325967117692513. doi: 10.1177/2325967117692513. PMID: 28321431; PMCID: PMC5347432.

Mourad F, Maselli F, Patuzzo A, Siracusa A, Di Filippo L, Dunning J, de Las Peñas CF. OSTEOCHONDRITIS DISSECANS OF THE RADIAL HEAD IN A YOUNG ATHLETE: A CASE REPORT. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2018 Aug;13(4):726-736. PMID: 30140566; PMCID: PMC6088130.

Bonazza NA, Saltzman EB, Wittstein JR, Richard MJ, Kramer W, Riboh JC. Overuse Elbow Injuries in Youth Gymnasts. Am J Sports Med. 2022 Feb;50(2):576-585. doi: 10.1177/03635465211000776. Epub 2021 Mar 29. PMID: 33780632.

Logli AL, Bernard CD, O’Driscoll SW, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Morrey ME, Krych AJ, Camp CL. Osteochondritis dissecans lesions of the capitellum in overhead athletes: a review of current evidence and proposed treatment algorithm. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2019 Mar;12(1):1-12. doi: 10.1007/s12178-019-09528-8. PMID: 30645727; PMCID: PMC6388572.

Bruns J, Werner M, Habermann CR. Osteochondritis Dissecans of Smaller Joints: The Elbow. Cartilage. 2021 Oct;12(4):407-417. doi: 10.1177/1947603519847735. Epub 2019 May 21. PMID: 31113206; PMCID: PMC8461164.

Bae DS, Ingall EM, Miller PE, Eisenberg K. Early Results of Single-plug Autologous Osteochondral Grafting for Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Capitellum in Adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2020 Feb;40(2):78-85. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001114. PMID: 31923167.