5 Tips To Reduce Shoulder Injuries In Men’s Gymnastics

Although I work with a lot of female gymnasts, I also work with a handful of male gymnast and many have shoulder problems. Unfortunately, I know from personal experience and through college teammates that shoulder injuries run wild in men’s gymnastics. I don’t know of one male gymnast that hasn’t had significant shoulder pain or an injury at some point in their career.

I will offer a lot of thoughts below, but for those interested, I recently made a comprehensive free guide to Gymnastics Pre-Hab, that has all the exercises, circuits, and concepts I teach male gymnasts to take care of their shoulders. You can get it here,

Download SHIFT's Free Gymnastics Pre-Hab Guide

Table of Contents

Daily soft tissue and activation exercises

Specific 2x/week Circuits for Male and Female Gymnasts

Descriptions, Exercise Videos, and Downloadable Checklists

I have heard way too many stories of gymnasts going through multiple surgeries or losing entire competition years due to shoulder issues. I hope that I can start spending more time teaching male coaches and athletes about proactive shoulder care to possibly reduce the high rate of shoulder injuries for the next generation. If readers currently are struggling with shoulder pain, remember full evaluation and individualized treatment is the best approach. With that said here are 5 points I think are important to consider, with lots of videos to help out.

1. Maintain Soft Tissue Mobility

Men’s gymnastics requires an extraordinary amount of shoulder strength. It’s natural for male gymnasts to develop lots of upper body musculature over time. Obviously this is a key to success in mens gymnastics, but it’s important we do not let it get too far gone to the point where athletes grossly lose their shoulder mobility. Excessive stiffness in the lats, pecs, biceps, and teres major in particular can be an issue. If this soft tissue becomes very restricted, it can negatively affect planes of mobility needed for skills, as well as throw off the normal biomechanics of the shoulder. In my opinion, I think male gymnasts should make this a priority through regular self soft tissue work and manual therapy. Here are some short videos that some soft tissue mobility drills.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PYMao0YWzkc

As an important side note, we want to make sure the stretches we do are targeting soft tissue and not putting stress on the wrong areas. Check out this video tip from a few months back that goes over this concept.

2. Maintain Thoracic Mobility

Thoracic mobility can also become very limited if a gymnast spends a ton of time in a hollowed or rounded shape. Again we need this rounded shape as it is fundamental to gymnastics, but we don’t want it to become excessively stiff creating a loss of thoracic extension and rotation. Full thoracic mobility is essential for overall shoulder motion. A gross loss of thoracic mobility is correlated with a variety of shoulder issues, especially as male gymnasts move into optionals and do mobility demanding skills like jams, ring giants, and one arm skills on high bar. A few thoracic mobility drills, along with some wall angels progressions are usually what I like to give people as daily pre-warm up drills.

(props and credit to the FRC crew for that one)

3. Regularly Work Basic Rotator Cuff and Scapular Strength

Some of these isolated shoulder exercises have gotten a bad rap lately, as people worry they are working individual muscles and are not truly “functional”. Although they certainly are not the only thing we should be focusing on, they are a very important part of the puzzle to shoulder health. In conjunction with the point above, many male gymnasts can go through years of training and develop large imbalances around the shoulder joint. This imbalance can refer to planes of motion (horizontal pulling to horizontal pushing, vertical pulling to vertical pushing), left to right asymmetries, and also in terms of larger to smaller muscle groups. We don’t want the lats, pecs, and other prime mover groups getting significantly more dominant than the smaller muscles of the rotator cuff and scap.

Male gymnasts must have an incredibly strong, balance rotator cuff to provide co contraction and joint compression. Their shoulder blades must also be very developed, supporting proper biomechanics and shoulder joint position during skills. This helps to avoid excessive strain to passive tissues like the labrum or other tendinous structures of the rotator cuff/long head of the biceps over time. Here is another short video that goes through some of the basics I regularly prescribe to male gymnasts I work with. Many people use therabands which is fine (and ideal for a travel situation), but whenever I can I try to use dumbells as it is more objective to track and allows for some more focused exercises.

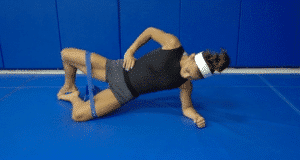

4. Train Dynamic Stability

Having mobility and underlying strength are very important. The next area to keep up on is dynamic stability of the shoulder joint. This is where things start to blend into more control focused, as well as working in full range of motion patterns that are gymnastics skill specific. There are a few ways to go about this, both through manual therapy and specific exercise selection. I think hands on stability work with healthcare providers or other movement specialist is very important, but I also think using external load like kettlebells is useful for male gymnasts. This theoretically helps build subconscious control to different movements planes.There is also a thought process that working full range control builds movement variability to help deal with inevitable errors the shoulder joint will encounter.

Male gymnasts especially need end range control for advanced strength skills on rings (crosses, maltese, Azarians), pbars (Diams, healy) and various rotational skills on high bar (eagles, jams). I feel it must be trained from an early age with the correct programming, technique, coaching, and progression. Here are a few drills I like, but there are many more beyond this.

5. Caution Heavy Ring Strength In Early Years

In a lot of the talks I have had with coaches and some higher level athletes, the importance of delaying heavy ring strength in early comes up frequently. I think working spotted positions, technique and light strength work at a young age is important and safe. However, we don’t want to be hammering away on heavy ring strength when athletes have not gained muscle mass, gone through puberty, or are having rapid growth spurts when they are more at risk. I have no perfect scientific answer for when to start and exact timing, but I strongly suggest tracking growth regularly as one method for helping and also developing individualized plans for each athlete. We must also have a very well planned, periodized, progressive strength program to use as a base.

Bonus #6. Work with Healthcare Providers Proactively

The importance of working with a skilled, knowledgeable healthcare provider can’t be over stated. In one sense, they can be very helpful to perform manual therapy, strength, and dynamic stability mentioned above. Along with this, they can be a direct point of access to screen early for injuries. Being able to screen for losses of mobility or gross imbalances, as well as being able to pick up on small injuries early can go a long way for long term shoulder care. They don’t necessarily need to be a former gymnast, but more so open to learning about the sport and know movement demands.

Conclusion

This is really just the start of the conversation, I hope to have more formal information and videos to offer people in the future. Shoulder injuries are the biggest injury issues in the mens side of the sport, and being a former gymnast I have gone through my fair share of shoulder problems. Hopefully we can help progress our approaches using the best available science to make a dent in this for the next generation. Best of luck, and hope this is helpful for all my fellow male gymnasts out there.

Dave Tilley DPT, SCS

References

- Andrews, J., Reinold, M., Wilk, K. The ATHLETE

’s Shoulder. Second EDITION

’s Shoulder. Second EDITION , 2009

, 2009 - Wilk KE, Macrina LC, Reinold MM. Nonoperative rehabilitation for traumatic and atraumatic glenohumeral instability. North Am J Sports Phys Ther 1(1):16-31, 2006.

- Wilk KE, Arrigo CA, Andrews JR. Current concepts: The stabilizing structures of the glenohumeral joint. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 25(6):364-79, 1997.

- Wilk KE, Andrews JR, Arrigo CA. The physical examination of the glenohumeral joint: Emphasis on the stabilizing structures. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 25:380-9, 1997.

- Cordasco FA. Understanding multidirectional instability of the shoulder. J Athl Training 35(3):278-285, 2000.

- Reinold M., Wilk K: Treatment Of The Shoulder: Principles of Dynamic Stabilization DVD

- Manske R., et al. Current Concepts In Shoulder Examination of The Overhead Athlete. IJSPT Oct 2013; 8(5): 554 – 578

- Andrews, J., Reinold, M., Wilk, K. Current Concepts in the Evaluation and Treatment of the Shoulder inOverhead Throwing ATHLETES

, Part 2: Injury Prevention and Treatment. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach 2(2) 2010

, Part 2: Injury Prevention and Treatment. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach 2(2) 2010 - Paine, R., Voight, M. The Role of The Scapula. IJSPT: 8(5): 617 – 629; 2013

- Caine D., et al. The Handbook of Sports Medicine In Gymnastics. First Edition. John Wiley and Sons, 2013Cook G., et al.