Hip Injuries in Gymnastics – A Complete Guide

Hip pain is extremely common in gymnasts. Despite the research saying that only 3.1-5.7% of all injuries in gymnastics occur in the hip, the reality is that it is much more common. Injuries like hamstring growth plate inflammation (ischial apophysitis), hip flexor strains, and labral tears can plague gymnasts for years.

Sometimes these injuries reoccur and significantly hinder a gymnast’s ability to train or compete. They can get so bad they require surgery to fix. Worst of all, these injuries may be so persistent that it causes a gymnast to quit gymnastics altogether for quality of life and long-term health reasons.

As a former collegiate gymnast, and a current gymnastics coach/Sports Physical Therapist specializing in gymnastics, I know that thousands of gymnasts suffer. They think their hip pain is “part of gymnastics” or are told that due to the flexibility and skill demands, they should just “get used to” chronic hip flexor and hamstring strains. This is not true. Yes, injuries are a part of sports and hip injuries are more common in gymnastics, but I don’t think that means we should just accept hundreds and hundreds of gymnasts getting them.

While it’s common for a gymnast’s hips to have pain, it is not normal. Soreness from challenging strength and training is one thing. Pain from inappropriate flexibility methods, mismanaged workloads, and pushing a young gymnast too hard too soon, is completely different.

It is crucial that a gymnast get the proper evaluation, and accurate diagnosis, for their hip pain. A common misunderstanding in the medical and gymnastics world is that gymnasts just need to do more flexibility and glute exercises like clamshells to fix their hip injury. This is very misguided. It is true that soft tissue mobility and glute strength are important parts to hip health and performance in gymnastics. But, there are many other factors that I will cover below that are crucial to understanding. I have treated 1000s of gymnasts for hip pain in my career and can tell you that only focusing on stretching and low-level glute exercises is not enough to make substantial progress for hip injuries.

Due to how many gymnasts struggle with hip pain, and how many medical providers ask me about how to help them, I wanted to create a “mega” blog post and podcast resource for people. My hope is that by taking the time to really break down everything in-depth, parents, medical providers, and anyone else working with gymnasts, can have this blog post as a reference.

After this short introduction, I will start by outlining how common hip pain is in gymnastics. I will then review some of the biggest factors that might be most important to understand as to why these injuries occur. Following this, I will break down the basic anatomy of the hip joint and the most common injuries we see frequently in gymnasts.

Then, I will walk people through the 4 main phases of injury rehabilitation, share the exact exercises/approaches I use with gymnasts, and talk about returning to sports safely. To conclude things, I will discuss some ways that we can work together to reduce the risk of back injuries in gymnastics and offer help for people who may be really struggling with ongoing pain.

Table of Contents

In-Depth Courses for Gymnastics Coaches and Gymnastics Medical Providers

Before going down the rabbit hole, I know that many people want a “step by step” instruction guide for fixing gymnastics hip pain. My very popular Gymnastics Medical Course – Current Concepts in Evaluating and Treating Lower Extremity Injuries in Gymnastics – covers exactly how I rehab hip injuries in gymnasts. If you want to learn about that, and get 8.5 hours of AT/PT CEU credits, the link is below!

If you are a gymnastics coach, I have 40+ of webinars, handouts, and discussion boards inside our online gymnastics education group The Hero Lab. We cover everything from flexibility, to strength, to culture, and more while getting access to live Q&A.

If you prefer to listen to this in podcast form or watch it in video form, you can check those out here!

How Common is Hip Pain in Gymnastics?

To first understand how common hip injuries are in gymnastics, let’s review some epidemiological studies. These are studies that look at the rates and prevalence of certain injuries within different areas of gymnastics.

- Kerr 2015 in NCAA Gymnasts, 11 programs with 418 injuries over 5 years

- Hip joint was 4.8% of all injuries

- Chandran 2021

- 3.9% of all injuries in NCAA 2014 – 2019

- Kolt 1999 of 64 elite and sub elite gymnasts over 18 months

- Hip joint was 5.7% of all injuries

- Salun et al 2015, 21 year study of 3681 injuries from elite/intermediate/novice level

- 3.1% overall incidence,

Why Is Hip Pain So Common in Gymnastics?

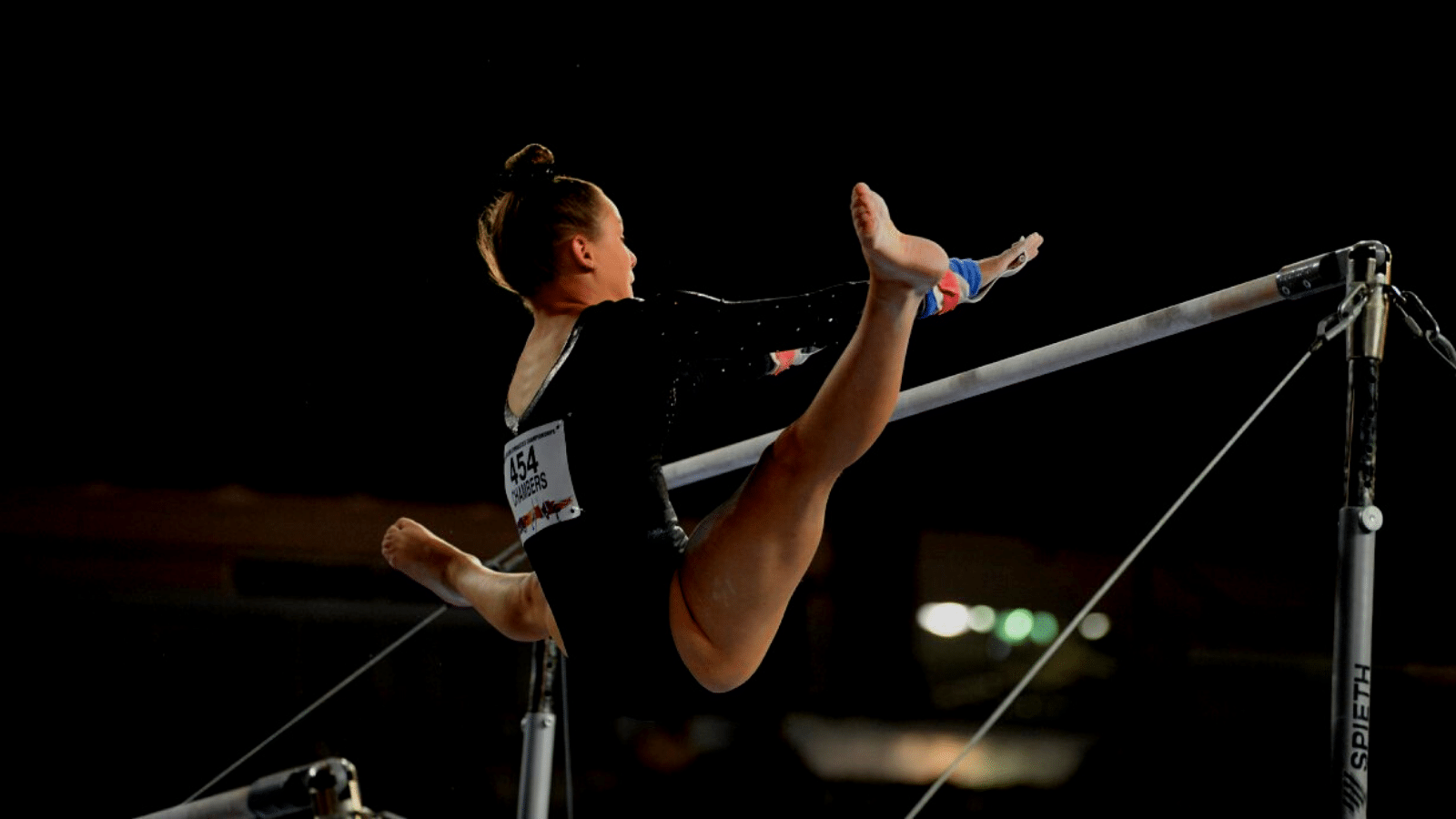

Gymnastics Uses Arms As Legs

At the biggest picture level, gymnastics is an extremely unique sport that has athletes using their arms as legs. The hip joint is not inherently built for these very large ranges of motion like the shoulder is, and expriences very high forces at end ranges of motion. Skills like switch leaps, ring leaps, stalders, and others can be very taxing on the hip joint structures and musculature.

The anatomy of the hip joint is very much designed for stability, not mobility. It has a deeper socket than the shoulder, allowing it to be what we put thousands of miles of walking on. It helps us handle the forces of running, jumping, and landing. But, the trade-off is that it does not allow for very large ranges of motion. For these reasons and more, we must be more cautious with extreme high-level gymnastics skills so we do not negatively stress the hip joint.

High Skill Repetitions

The harsh reality many people may not want to admit is that gymnastics training places insanely high repetition numbers on gymnasts. Our sport’s culture promotes a very high, often open-ended repetition requirement for skills. Between all the drills, skills, routines, side stations, and extra physical preparation work, the hips of gymnasts can easily reach the thousands per week. While this is not inherently a bad thing, if left unchecked it can be a huge catalyst for pain and injuries to occur.

The proper dose of skill repetitions can be useful, as they help build up performance and increase the hip’s capacity. But, the incorrect dose of active flexibility work, skills, sprints, side stations, or drills can easily cause a flare-up. To truly insulate gymnasts against big hip injuries, we must be aware of how many repetitions of skills they are doing each day and week. We must also carefully plan out similar types of repetitive movement patterns (like hip flexing and kicking) between events. This helps to make sure we do not accidentally overload them.

High Skill Forces

While the repetitions of skills are by far one of the biggest factors for why a gymnast may develop hip pain, we can not deny the reality that the forces that gymnastics puts on the hip of a gymnast are enormous. In an effort to help condense some of the research around this (mor in this book here and here), here is a list of forces that have been recorded.

- Peak ground reaction forces on leg: 8.8-14.2x BW

- Controlled laboratory landings: 15x BW

- Highest landing forces from dismounts suggested 18-30x BW

- Straddle splits caused femoral head displacement of 10.8cm in elite ballet dancers

- Switch leaps? Switch side? Ring jumps? Unknown but major pain generator

These forces really are staggering. We don’t need to be terrified by them, but more so respectful and aware of them. These skills, and many others, can all safely be trained and performed. The key here is to make sure that proper technique, progressions, workload management, and strength/physical preparation are used to help manage risk.

High Flexibility Demands

One of the clearest factors for hip injuries in gymnastics is the massive amount of flexibility required for skills. While these large ranges of motion definitely make gymnastics one of the most impressive sports in the world, it often comes at a cost. As mentioned above, when elite ballet dancers had x-rays taken of their hips in a straddle split, there was a notable amount of hip joint subluxation that had to occur for full a 180-degree angle to be reached. There is also other X-ray evidence that this occurs in gymnasts during oversplits.

What this tells us is that in order to reach these extreme ranges of motion for splits/oversplits, jumps, leaps, stalders, and other skills, many things must go right. Not only does someone need to have the underlying boney structure that supports it, they also need significant joint capsule hypermobility and soft tissue flexibility. The reality is that not every gymnast will have these things. As a result, not every gymnast is going to fit the mold of a very hypermobile athlete who can reach full splits and perform skills that have these massive ranges of motion requirements.

It’s not that we can’t continue to train and improve flexibility, it’s more that we must recognize there is a wide range of body types in gymnastics. If we do not have the proper tools to screen for flexibility and do not follow the best current science-based methods on how to safely improve range of motion, it can easily become a situation where hip pain and injuries occur. This is crucial to remember, particularly in relation to hamstring growth plate injuries and labral tears.

Lacking Science-Based Flexibility Methods

This is typically a tough pill for people to swallow. While there has been substantial progress made in the culture of gymnastics, the reality is that we still are not using the most current science-based information when training flexibility. Gymnasts are commonly “loose and tight” and the same time. By this, I mean loose-jointed, but still having tight muscular structures.

In this situation, if proper flexibility methods are not used, it’s easy for the joint and passive structures like ligaments/labrums to get overly stressed. As this paper shows, doing very long 2+ minute holds at end ranges of motions (like commonly seen in warm-ups for oversplits) may not be the most effective method for increasing range of motion. Consistent, daily flexibility work based off of a thorough screen at least 5-6 days per week that aims for about 2 sets of 30 seconds of soft tissue biased stretching per muscle group is likely the best dosage.

On top of that, contrary to what many inside gymnastics believe, regular stretching does likely not make muscles truly longer. As this paper and this paper suggest, it is likely more of a desensitization process through receptors called nociceptors. While there is some evidence that over time the passive elements of tendons and muscles can increase their compliance, it likely is not the main reason long-term changes stick.

In order to change the actual muscle tissue itself, we likely need to be incorporating things like loaded eccentrics and science-based strength and conditioning methods that utilize weight training (more below). We also need to make sure that the muscular tissue itself, and no the ligaments or joint capsules, are the things being biased. For this, we need to study the hip anatomy in-depth and make sure we adjust certain flexibility stretches. This may not look as aesthetically impressive, but it will be better for both gymnastics performance and hip health.

Gymnasts Being Young & Pre Puberty

Another reality of gymnastics – the majority of athletes training in our sport are children. Despite ages trending upward for the world and Olympic teams, the vast majority of people competing in gymnastics are under the age of 16. They are young kids, who have yet to fully develop physically or mentally. This means, according to great research and textbooks, they are nowhere near their peak strength, power, or cardiovascular capacity.

Not to mention, their growth plates are wide open and very vulnerable to injury. If gymnasts are not developed enough or lack the physical preparation to protect their hip joints and open growth plates, injuries muscular spasms or joint damage might surface. It’s crucial that young gymnasts have the core, leg, and general strength to help buffer these high forces going through their hip joints that are not fully formed yet.

Gymnastics is a very unique sport where very young kids ages 8-12 are asked to perform very high force skills, in high amounts, and are training 20+ hours per week in some situations. In some areas of the sport, particularly those trying to get on the pre-elite/elite or NCAA track, it can create a difficult time period where pre-pubertal athletes are training high force skills, in high repetition, well before their bodies are physically or mentally capable of handling it. This is where expert coaching, training plans, and pacing comes must be a priority.

Lack of Science-Based Strength & Conditioning Methods

This is something that applies to all gymnastics injuries but in particular the hip. As mentioned, the forces on the hip joints of gymnasts are massive. If you look at the sports medicine literature, it’s clear that other sports use science-based strength & conditioning to help reduce the risk hip, knee, and ankle injuries in particular. This includes evidence-based, progressive weight training using dumbbells, kettlebells, medicine balls, and barbells.

Based on great literature (more here, here, and here), it is clear that a properly done, properly coached, and properly progressed strength and conditioning program is beneficial for performance and reducing the risk of injuries. This includes a combination of both external weight lifting and bodyweight strength work. This type of training is huge to help build the core and glute muscles, and the other dynamic stabilizers, to protect the ligaments, tendons, and joint capsules in the hip.

Despite the abundance of evidence, there is still a huge percentage of gymnastics professionals who feel that gymnasts should not be lifting weights. They fear myths and misunderstandings about weight training, believing that it will make gymnasts “bulky”, less flexible, and cause injuries. However, a closer look at the literature show this to be largely false, given the program is properly implemented and coached with an aim of improving explosive power. Even more so, it is clear that weight training is not only not dangerous for kids, but likely helpful in reducing injury risk.

As a result of this cultural barrier, many gymnasts do not get the adequate core/leg strength and capacity needed to handle the high-impact forces going through their hip joints. Not to mention, they are putting a huge bottleneck on their potential to train and compete for high-level skills. Gymnastics is a sport based on explosive bodyweight power. The same thing that helps improve this power will also help mitigate the risk of back injuries, both overuse and acute. For more information about this topic check out this popular blog post I wrote in 2016.

Also, if you would like to read my “Ultimate Guide to Gymnastics Strength” – you can check it out here.

Improper Landing Techniques Still Taught & Used

Another huge change that must be made in gymnastics to reduce the risk of hip pain injuries is a sport-wide adoption of using science-based landing mechanics. It is unclear whether this comes from a lack of education, an ‘old school’ mindset, or a desire to mimic the esthetic type landing seen in ballet or dance.

However due to this, many people in gymnastics still teach use, and judge, based on a landing position that is not supported by science to ideally help dissipate high forces. Many gymnasts still land with their feet together, torso upright, hips tucked under, and in a ‘knee’ dominant patterns that may shift more stress onto the back, knee, and ankle joints. In fact, it was recently shown in a study of elite gymnasts in the UK, that they tended to land with a ‘stiff’ landing pattern with an overextended lower back position.

This is in contrast to the suggested landing pattern, supported by enormous amounts of data, of a squat-based landing that has the feet hip-width apart, knees tracking in line with the hip and feet, and the allowance of squatting to parallel depth so various musculature can be recruited to buffer forces.

Until this becomes the gold standard for teaching gymnasts how to land in practice and competition, we may continue to see high back pain rates. I recently gave big presentations to the coaches and judges in the NCAA about this topic that you can check out here.

Sport Culture – Early Specialization

One of the most important, yet most challenging, issues at hand is changing gymnastics culture. The last five years have clearly shown us that there are many dark corners of a gymnastics training culture that exist in “old school”, archaic methods being used. There has been a massive amount of scientific data published around early specialization (here and here), year-round training (here and here), strength and conditioning (here and here), workloads (here and here), that have yet to make their way into mainstream gymnastics training.

Early specialization, when an athlete chooses to only participate in one sport, is one of the biggest concerns. It is common to hear gymnasts being told they will ‘miss their shot’ if they don’t only do gymnastics from a young age. While I do believe that gymnasts, particularly those with high-level goals, may need to specialize earlier than most sports, asking a 6 or 7-year-old to only train in gymnastics and not experience other sports is asking for disaster.

There is great evidence that this is concerning for increasing the risk of burnout, overuse injuries from repetitive movement patterns, and that it may negatively impact their overall athletic potential long term. The majority of the literature suggests that 14 or 15 years old is ideal for specialization. With that in mind, I think that may be unrealistic for many gymnasts, and that 10-11 might be a better target.

But hearing about gymnasts specializing at 8 years old, as studies including one in the NCAA I was part of have suggested, is definitely concerning for all injuries. This is something our sport desperately needs to talk about and change to protect young at-risk gymnasts. While there is a large range of movements in gymnastics, the repetitive impact of only doing gymnastics from a young age might be a big reason so many lower back injuries are so common.

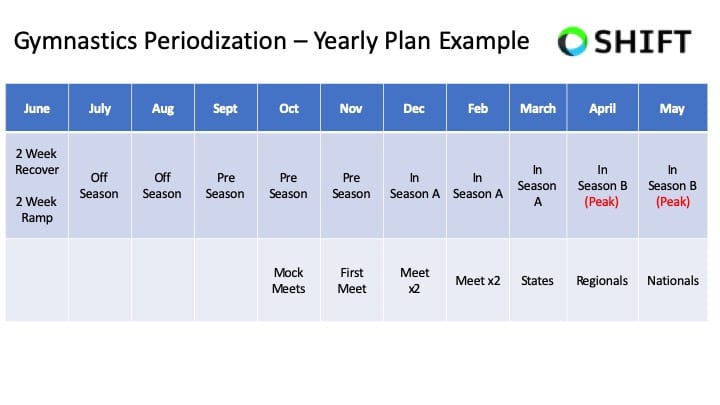

Sport Culture – Year-Round Training

Year-round training is another concerning cultural phenomenon that continues to persist in gymnastics. As with early specialization, there is an abundance of research across many sports (more here , here, and here) suggesting that athletes who train more than 9 months out of the year in a single sport are at elevated risk of injury and burnout. This has been well studied in baseball, which is a sport I’m fortunate my mentors Mike Reinold and Lenny Macrina were pioneers in alongside current studies like this.

I strongly feel that creating relative off-seasons, using periodization, and utilizing cross-training are crucial for reducing back injury risk and optimizing performance. The reality of our sport is that there has never been a time when gymnasts followed evidence-based guidelines around recovery, offseasons, and science-based work to rest ratios.

My hunch is that remodeling our year-to-year approach, shortening competitions seasons, and giving athletes a relative off-season after their hardest meet, would yield massive improvements in health and performance. I think the COVID pandemic is a further support piece of this, where many gymnasts said that after 2-3 months off, they felt the best they have ever felt mentally and physically. I don’t think it’s wise to give gymnasts extended periods of time fully off each year (3+ months for example). Hower, 4-6 calculated weeks would likely be incredible for athletes, coaches, and parents.

Lack of Science-Based Workload/Wellness Monitoring Programs

Workload, athlete monitoring, and periodization are all areas of research that have become very popular in sports around the world. It is very common to hear about sports like soccer, basketball, and baseball utilizing specific workload tools to help plan and manage training volumes in athletes.

While there has been more conversation about workload management in gymnastics, the current approach still largely depends on a coach’s perception for decisions to be made. This was recently shown in Rhythmic Gymnastics but is likely the case in other domains such as artistic, trampoline & tumbling, and more.

The truth of the matter is that while there is some data in gymnastics forces, we still have a tiny fraction of what is needed to create evidence best training plans around impact and health. We have no idea what the impact forces on the back joint are for a Tumbl Trak, vs Trampoline, vs a rod strip, vs a new spring floor, vs an old spring floor, vs a spring floor with a sting mat for take-off or an 8″ mat for landings. By not knowing these numbers, and by not having a logical progression of forces over multiple weeks, we are essentially asking coaches to fly a plane without any speedometer or gas gauge. It’s insane, and a huge reason we continue to see so many gymnasts struggle each year.

If we hope to curb the rates of back pain in gymnastics, it is imperative that we look into better tools for external and internal workload tracking. Without knowing what the forces of different surfaces are on the foot/ankle, and how to keep a close eye on the training load gymnasts take, it’s like trying to fly a plane without any gauges or speedometers.

While this is evolving in gymnastics and is a field I’m actively doing research in (see below), the reality is we still have a long way to go. We desperately need research to be conducted on the different forces on the back joint during tumbling, vaulting, and dismounts. We also need better systems in place to monitor how athletes are responding to gymnastics-specific training. This will help us enormously to plan, track, and keep in touch with how gymnasts are doing.

Gymnastics Basics/Foundational Technique Sometimes Not A Focus

On the sport-specific side of things, it has to be mentioned that technology itself is a huge factor in injury risk for gymnastics. While there is not as much scientific evidence looking at different types of gymnastics skill techniques, it’s paramount the gymnasts are taught proper basics, foundational techniques, and progressions.

This is particularly true for the lower levels, where proper tumbling, vaulting, and bar technique is crucial. Gymnasts must be put through the proper technical progressions skills and events to make sure they are equipped to handle the high forces of skills. If these foundations are not set from an early age, and a constant focus as the gymnast progresses in level, it might create high-risk situations. Making changes here comes down to better coaching and education systems throughout the world, to share. the optimal technique and progressions to keep gymnasts as safe as possible.

Equipment Technology Progression

Lastly, there is no denying that the sport of gymnastics has become exponentially harder in the last 10 years as equipment technology progresses. The spring floor, the vaulting table, the trampoline beds, and other advancements have helped skyrocket the level of skills being performed. The double-edged sword here is that this also increases the average force the body takes.

While the landing surfaces and matting have also increased in their ability to protect athletes, the net increase in force is still substantially higher in today’s gymnastics environment. It also creates a small ‘ripple effect’ on the younger generations, where the nature of harder skills being performed means that more time, effort, and possibly starting to learn these skills at a younger age, also occurs. Coaches must be trained on how to use different equipment for proper progressions, and we also have to financially support gyms that need better equipment to keep athletes safe.

Basic Hip Anatomy As It Relates to Injuries

I by no means am here to bore people with a dissertation in anatomy. But if we wish to make a change in the rates of back injuries, we must first understand the anatomy that contributes to those injuries. This helps to understand the nature of common injuries and leads us down the road of helpful strategies to reduce risk. To best do this, I will mirror the available literature studies that describe layers of the hip. Keep in mind I have modified the terminology and layout slightly the lean into the less medical diagnostic organization.

If you want all the scientific textbooks and anatomy references to look up, check out this textbook as well as some helpful research articles here, here, and here.

Layer 1 – Bones (Osseous Layer)

The best place to start for the hip joint is with the bones as a base layer. The pelvic base has 3 subcomponents of the ilium, ischium, and pubis. But more importantly to the hip joint are the socket (acetabulum) and ball (femoral head).

Socket (Acetabulum)

On one side of the hip joint is the actual socket, which is part of the pelvis base. This socket is much deeper than that of the shoulder as I have mentioned. It allows us to be upright, walk, and take high-impact forces. But, in the exchange for less mobility. The boney aspects of the socket do have cartilage layered on top to help buffer high-impact forces.

The socket covers about 170 of the ball known as the femoral head. It has more boney coverage in the back than in the front, which is one reason why we can kick our leg really far up in the front but not behind us in the back. It’s also worth noting that it is tipped forward and outward slightly.

Ball (Femoral Head)

Meeting the socket of the pelvis is the ball of the femur. This is called the ‘femoral head’ and it’s one end of the very long femur bone. This sphere-shaped structure fits very snugly with the socket. It also has its own set of cartilage that helps to protect the boney surfaces and buffer forces.

The structure of the head of the femur is generally similar from person to person but does have massive amounts of individual differences in its geometry. It can be a bit less or more angled into the socket, it can be turned inwards or outward, and can have different curvatures.

It’s also important to note that sometimes, overgrowth of the boney areas can develop. If excessive bone is laid down on the socket side of the joint, it is called a pincher lesion. If excessive bone is laid down on the ball side of the joint, it’s called a cam lesion. If this develops in both areas, it’s called a mixed lesion. While not as common in the more hypermobile gymnast population, it can sometimes occur if excessive boney contact is made between these two areas which is referred to “FAI” or Femoroacetabular Impingement.

Layer 2 – Ligaments/Joint Capsules (Capsulolabral Layer)

Joint Capsule

Moving on to the second layer, there are many crucial components here, particularly for gymnasts. First, there is a more general joint capsule that is a saran wrap type covering encapsulating the hip bones and joints. This encapsulation not only helps to secure the joint even more, but it also holds a key fluid called Synovial fluid. This fluid helps to lubricate and hydrate the joint, as well as provide nourishment.

Ligaments

From the joint capsule, there are very important thickenings within this tissue that provide extra stability as the leg moves in certain directions. I will keep this simple and basic for people, but for those who want more depth check the papers above.

If you are a visual person, THIS article has fantastic pictures of the ligaments I will outline below – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30475277/

Iliofemoral Ligament (ILFL)

The first main ligament is located on the front of the hip, the Iliofemoral Ligament is also called the Y ligament or the Ligament of Bigelow. It starts from the AIIS of the pelvis bone, and branches into two arms. The Lateral arm moves obliquely and attaches to the great trochanter. The Medial arm travels inferiorly and attaches to the front of the femur.

The main role of this ligament is to limit end-range hip extension and rotation. So think the back leg of a split or switch leap, or when someone sprints. It also works to prevent excessive forward of the femoral head out of the hip socket during these motions. It does have a secondary role in limiting hip external rotation when the hip is flexed.

Pubofemoral Ligament (PFL)

The second main, the Pubofemoral Ligament, starts on the front of the pelvis bone and travels inferiorly and posterior wrapping around the ball of the femur like a hammock. It does not directly insert onto a bone, but blends in with the joint capsule.

Its main role is to limit external rotation, especially in hip extension, but it also plays a key role in end-range hyper abduction as you would see in a straddle split or straddle jump. The hammocking type alignment of this ligament helps prevent inferior gliding of the femoral head in these extreme straddle positions.

Ischiofemoral Ligament (ISFL)

Lastly is the Ischiofemoral Ligament. This ligament starts on the back of the pelvis, wraps upward and laterally, and inserts on the great trochanter. It limits very end ranges of hip flexing and rotation, and also restricts posterior gliding of the femur.

it’s worth noting there are two other structures, the Ligamentum Teres and Zona orbicularis, that are important structures of the hip for blood supply and proprioception. But, in an effort to not make these overly complicated I will not be spending a ton of time here.

Labrum

One of the most important passive structures of the hip that does require discussion is the labrum. The labrum is a horseshoe-shaped structure made up of fibrocartilage. It ranges from 3-8mm wide and 5mm or so thick. It serves many important purposes.

For one, it increases the acetabular area by about 25% and the acetabular volume by 20%. It also acts as a seal between the central and peripheral compartments of the hip, creating and maintaining negative intra-articular pressure.

Along with this, it serves a crucial role in buffering and transmitting high-impact loads. In a way, it serves a bit like a meniscus for the knee. By providing shock absorption and more surface area, no one area can get overly stressed. This type of architecture allows us to run, jump, and perform high-force skills. Given its importance, we definitely want to make sure we don’t overstress it.

Also, we want to make sure we don’t get any tearing in it. Notable tears can cause a loss of the intra-articular negative pressure and possibly increase the micromovements of the ball inside the socket joint, known as microinstability. Not to mention, they can sometimes be very painful in themselves.

Layer 3 – Muscles (Muscular Layer)

As great as all these passive ligamentous and capsule structures are, by themselves they are nowhere near capable to handle the high forces of everyday life and sports. Also, they don’t provide the means to actually move the leg in different directions. This is where Layer 3, or the muscular layer, comes into play. These large, strong, and trainable muscular tissues allow for not only further protection of the hip joint but powerful movements of the hip joint for gymnastics.

Anterior

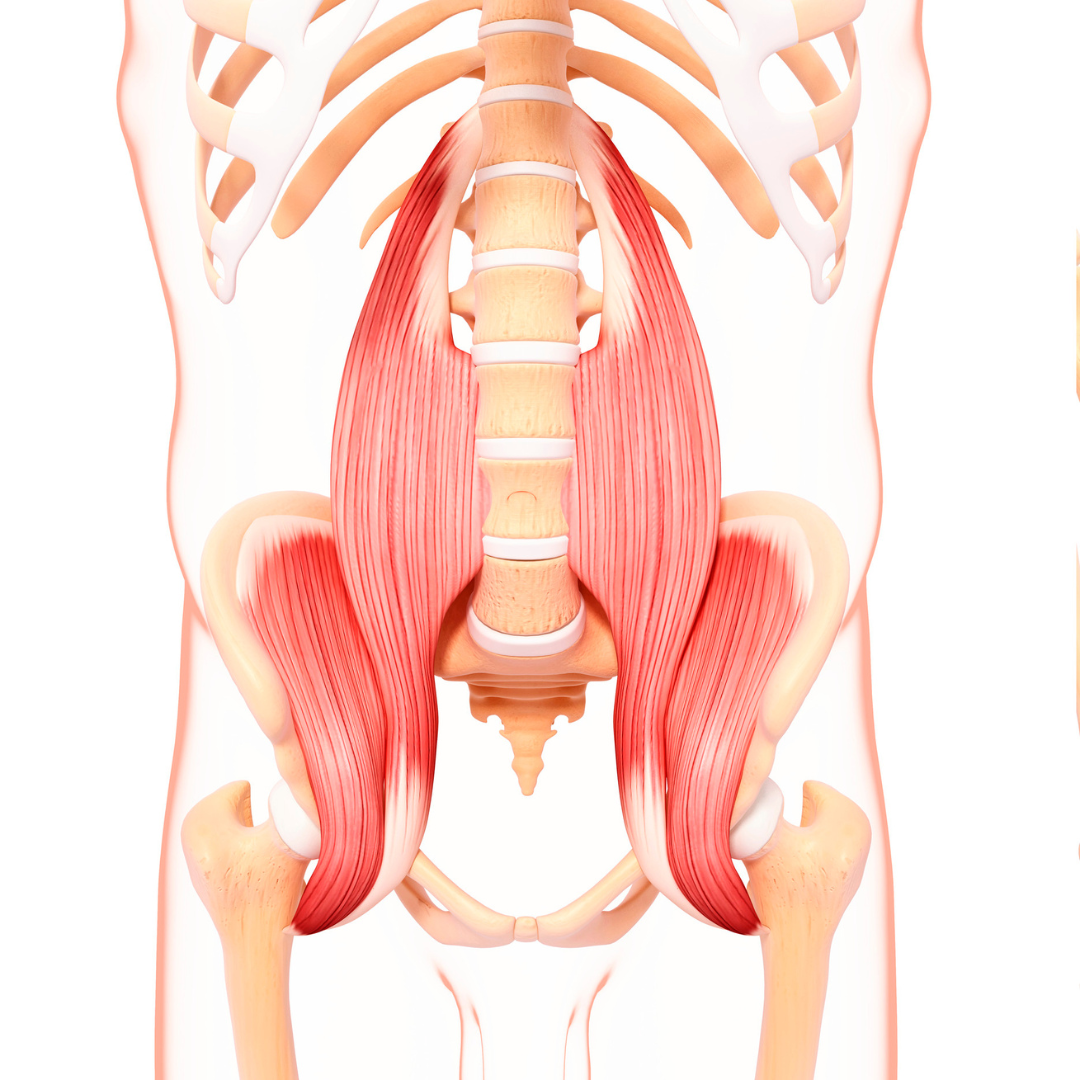

Iliopsoas

The first muscle on the front of the hip which many people are familiar with is the Iliopsoas, or hip flexor muscle. What many people are not aware of is that this muscle actually starts from your spine. This means that lower back position, such as overarching or hollowing, will influence this muscle’s length. From the spine, it travels down to the inside of the pelvis and attaches to the thigh bone on what’s called the lesser trochanter. It’s also worth noting that the lesser trochanter has a growth plate on it that can become inflamed in gymnasts and cause pain if it is overworked during growth periods. Its main role is to flex the hip upwards, as is seen in jumps, leaps, kicks, and running. It also helps to stabilize the spine.

Rectus Femoris/Quad

Closely related to the hip flexor is the Rectus Femoris. This muscle is one of the four quadriceps muscles. While the quad is typically more the focus in relation to the knee joint, the rectus femoris is worth noting here. For one, it starts on the pelvis at what is called the AIIS as opposed to the other 3 quad muscles that start on the femur bone itself. It also has a capsular reflection attachment. This means that the Rectus Femoris can help flex the hip, as well as straighten the knee. The Rectus Femoris is very important in particular for pulling the thigh forward when the leg is behind the body. This is seen in leaps, jumps, running, and other snap-in skills like cartwheels or round-offs.

Given its starting point on the pelvis, this muscle is subject to length changes depending on if the lower back is over-arched or over-hollowed. This must be considered for both hip flexor and quad stretching, as not having a proper hollow-core position may cause the muscle to not be the focus during the stretch, and instead may place more stress on the joint capsule.

TFL

The Tensor Fasciae Latae is a small muscle that starts from a boney prominence known as the ASIS, and blends into the Iliotibial band. The Iliotibial Band (ITB) is a large, flat, dense band of thick fascial tissue. The TFL helps to flex and internally rotate the hip, but also in combination with the other muscles attaching to the ITB

Sartorious

The Sartorius is another muscle that is less commonly discussed. It is along, thin, flat muscle that wraps from the front of the pelvis down to the inside of the knee, crossing two joints like the hip flexor. Due to its unique position, it serves to flex, abduct, and externally rotate the hip. It also can create a stabilizing effect due to its wrapping nature, providing stability.

*Adductor Brevis/Pectineus*

While not truly defined as anterior hip muscles, and more groin muscles, the unique positions of various positions of certain adductors allow them to assist the hip flexors. The Adductor Brevis and Pectineus are two muscles that fall into this category. Due to their orientation, they can assist in flexing the hip. This is particularly true when the leg is behind the body in a position of extension, as is seen in jumps, leaps, running, and other acro skills. This is important to remember for two reasons. One, gymnasts often have very stiff adductors as they do a lot back leg work moving from

Posterior

Glute Maximus

One of the most important muscles for both performance and hip health is the glute max. It is a very large, and powerful muscle that has various starting points and attaches to the gluteal tuberosity of the femur. It is key in extending the hip, as well as turning the hip out, which is the main driver of jumping, sprinting, and hip opening action. These are all key for almost all skills in gymnastics.

This muscle also is vital for absorbing high amounts of force during landing. Despite it being so important, it’s often overlooked and undertrained in gymnastics for strength development compared to the quads. While the quads, too, are important, it is the synergy of these two muscles along with the hamstrings and hip rotators that really allow for huge power outputs.

Semimebrinosis/Semitendinosis/Biceps Femoris

In combination with the glutes, the hamstring muscles also work for hip extension. Like the Rectus Femoris, these muscles all start from the pelvis and attach below the knee joint, making them able to both extend the hip and bend the knee. The hamstring tendon attaches to the ischial tuberosity, which has a large growth plate in younger athletes. Then, the hamstring tendon moves into the inside and outside of the leg hamstring group. On the outside is one hamstring muscle, the biceps femoris, and on the inside are two other hamstring muscles, the semimembranosus, and the semitendinosis.

Together they are a very strong muscle group, and can not only produce lots of power for jumping/sprinting, but they also work to slow the leg down during aggressive front leg kicking motions. So, they become very helpful as a “brake’ mechanism during running, jumps, leaps, and kicks. They also play a huge role in being able to snap the leg from this forward kick position, back down to underneath the body. For this reason and more, they must be trained regularly to help skill performance. They are also commonly irritated if flexibility methods are not science-based, or if workloads are spiked too high too fast.

*Adductor Magnus*

Like the pectineus/adductor brevis to assist hip flexion, the Adductor Magnus is to assisting hip extension. This large, very strong muscle group not only works to pull the legs together, but it also can help open the hip when it’s in a flexed position (think coming up from a squat). This muscle also serves a huge role in assisting the hamstrings and the glutes when accepting impact forces (think landing and moving into a squat). Like the hamstrings, this is often an area that doesn’t get enough attention in gymnastics for strength work.

Medial

As a whole, the adductors that reside medially on the thigh serve to pull the legs together. Along with this main role, they also play a crucial role in creating stability and balance when the leg is on the ground. This is particularly true for single-leg stance. The groin muscles work in coordination with the outer glute muscles to maintain balance within the hip joint.

Adductor Brevis/Pectneus/Adductor Magnus

In an effort to not repeat myself, please see the above sections for these muscles.

Adductor Longus

One muscle that has not been mentioned is the adductor longus. This large, fan-shaped muscle attaches from the underside of the pelvic bone and travels into a large area, then attaches to various points above and below the knee joint. Its main role is to pull the legs together (as in when a gymnast maintains good form) and it also serves a “slowing down” function with rapid straddle-type movements (like a switch side). Oftentimes, if a gymnast does not do enough groin strength work, or rapidly spikes the amount of jumps/dance work they do, they can strain this groin muscle.

Gracilis

The gracilis is another long, thin adductor muscle. It starts from the underside of the pelvis, like the adductor longus, and travels lengthwise down to the inside of the knee. Similar to the notes above, it helps to pull the legs together for good form, and also pull the legs back from a straddles position.

Lateral

The outside of the hip has many important muscles. For one, they serve to open the hip to the side which is very important for gymnastics skills. Two, they are very important to help maintain balance when on one leg (think beam leap landings and running.) Lastly, as it relates to hip health, they are crucial to maintaining balance and a good position of the ball of the femur in the hip socket.

Glute Medius & Glute Minimus

While these are two separate muscles, they generally function in a closer relationship so or ease I will discuss both here. The glute med and the glute min start from the top of the pelvis, on the iliac crest, travel down over the outside of the hip, and attach to the side of the femur bone. While they do function to bring the leg out to the side, into abduction, their more important role is for single leg balance and stability.

When performing skills or landings on one leg, this muscle group is massively important to prevent the hips from dropping inward with torso lean. Due to its role in single-leg landing, as well as dynamic kicking/jumping/straddling movements in gymnastics, we must be sure to pay special attention to developing it.

Deep Hip Rotators

Alongside the glute med and min, are the deep hip rotators. This is a group of 6 smaller muscles that all start on the back and outside of the hip socket on the pelvis, travel around the thigh bone, and insert into the outside of the femoral head. With this orientation, they are in a position to dynamically externally rotate the hip (think foot turnout). They are also massively important for preventing ‘caving in’ of the knee during landings. Lastly, they help create the straddle and ‘swim through’ motion of most straddle jumps, or release moves like toe ups/Tkachevs. Like the glutes, these multifaceted muscles need extra attention for both optimal performance and health.

Layer 4 – Nerves/Blood Vessels (Neurovascular Layer)

While not the most common type of injury seen in gymnasts, the various major nerves of the hip do warrant mentioning.

Sciatic Nerve

The sciatic nerve is a large branch that starts from the lower lumbar vertebrae, travels down through the buttock region, and then passes by the hamstring tendon as it runs down the entire length of the back of the leg. The sciatic nerve can become irritated when gymnasts have flexion/compression intolerant lower back pain, so that is important to screen and rule out if someone is having buttock pain.

As it relates to the hip, there are times when the sciatic nerve can become irritated or inflamed with high hamstring tendon or growth plate injuries. Gymnasts who have pain in the high back of their leg, and who also may have numbness/tingling, may have sciatic nerve irritation. There are also times when a gymnast’s hyper flexibility causes the nerve to get irritable during extreme stretching, say with oversplits or with the end ranges of leaps/jumps. Gymnasts who experience numbness, tingling, or traveling pain should be suspected of sciatic nerve irritation.

Femoral Nerve

Another nerve that is large and can sometimes be involved with hip pain is the Femoral nerve. This nerve is slightly higher in the lumbar spine, and travels down around the hip into the high groin area. While not commonly the sole reason for irritation, it is important to rule out as a possible false positive for groin pain.

Obturator Nerve

Similar to above, the Obturator nerve does not typically become the source of an isolated injury. But, it supplies the sensation and muscles on the outside of the hips, and as a result, should be kept in mind if someone is experiencing traveling pain, numbness, or tingling.

Layer 5 – Above/Below Joints (Kinetic Layer)

Spinal Mechanics

I have touched on this a few times, but due to the spine, pelvis, and hip joints all being virtually inseparable we must always consider them together. As the lower back arches, it causes the pelvis to tip into anterior tilt, which can drive femoral adduction and internal rotation (think knees “caving in”). Conversely, as the pelvis tips into a posterior tilt, this drives femoral abduction and external rotation (think knees “pushing out”). By keeping this in mind, we can work on lumbar spine mechanics and core control to help with hip pain, particularly during sprinting, jumping, landing, and squatting motions.

What Are The Most Common Hip Injuries in Gymnastics?

Location Categories of Hip Pain in Gymnast

Now that we have a basic understanding of how often hip pain occurs in gymnasts, and the underlying anatomy that is involved, let’s start tackling the major injuries that gymnasts tend to have as well as what causes them. To help keep things organized like above, we will follow the same approach as anatomy and break things into major location categories. We will first talk about common injuries in the front of the hip, and then the back of the hip, and then the inside of the hip, and lastly the outside of the hip.

Front/Anterior Hip

Microinstability (Caspulolabral Strains)

The first hip issue that is common in gymnastics and requires discussion is that of microinstability. Microinstability refers to small, but excessive and painful, movement of the ‘ball’ of the hip joint within the socket. This movement in itself is not a true injury by definition. But, it is definitely one of the leading causes of triggering hip irritation that many gymnasts struggle with.

There has been fantastic new research in this field over the last 5-10 years (find more here, here, and here). This research has pointed out that when more hypermobile athletes like gymnasts do skills that have high forces, at end ranges of motions, repetitively, it can start to create this micro-movement of the femoral head sliding around.

There are a variety of possible injuries that can occur with this repetitive microinstability. First, the joint capsule and ligaments surrounding the bones can become irritated. Second, the muscles trying to stabilize the joint can become strained. Third, as will be covered next, the labrum can become irritated and damaged.

Whichever occurs, it tends to occur because the underlying boney and ligamentous support (known as the ‘passive stabilizers’) are not able to fully handle the forces of the sport. Also, often times the muscles around the joint (known as the ‘dynamic stabilizers”) are also not strong enough to help out. Together, this can cause the hip joint structures to become painful and inflamed as they are put through these extreme ranges of motions at high speed as is seen with jumps, leaps, kicks, sprinting, and so on.

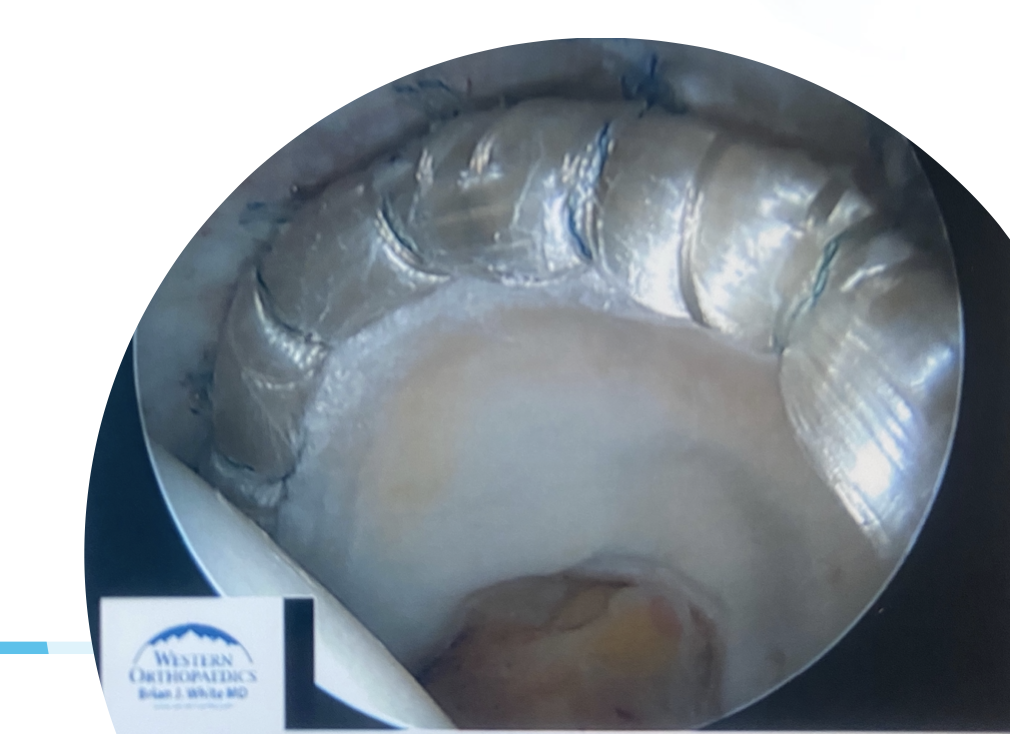

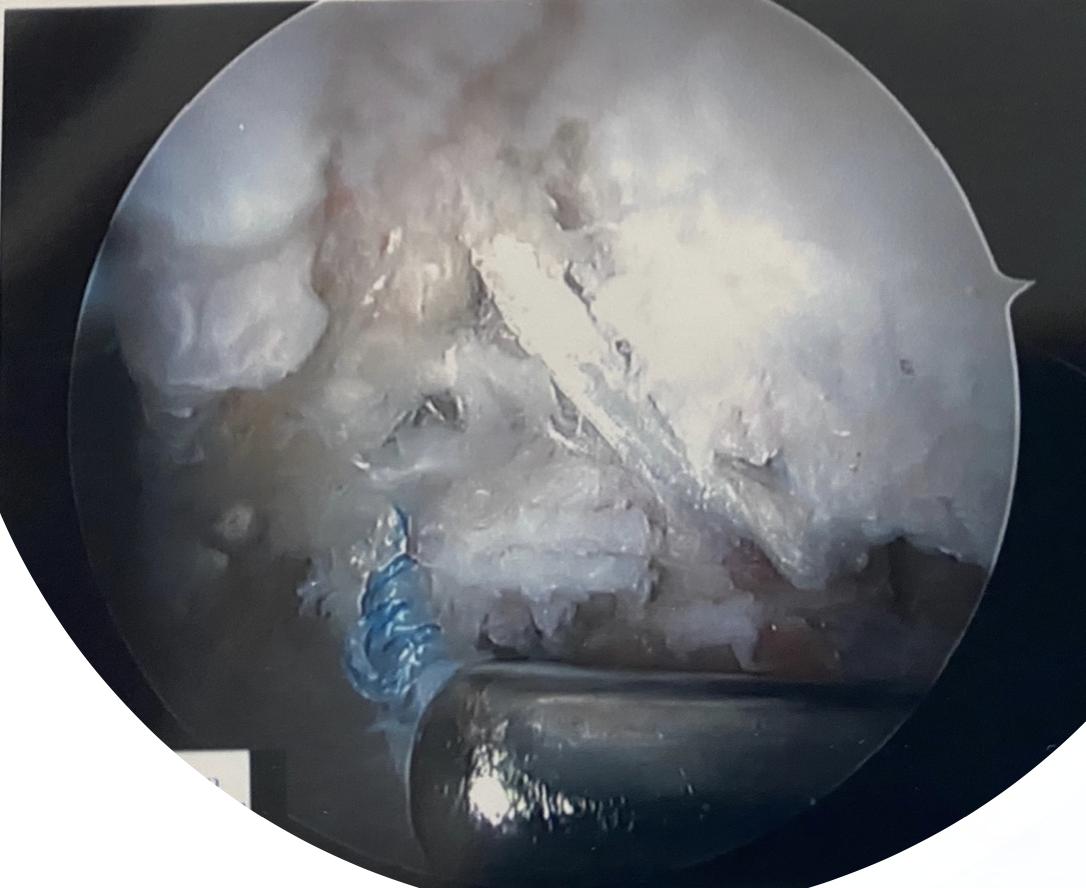

Microinstability (Labral Tears)

Closely related to microinstability and the injuries that occur due to that, are labral tears. Remember that the labrum is a fibrocartilage structure that deepens the hip socket, provides stability via a vacuum seal, and also helps buffer against high-impact forces. If there is a lack of boney support in a gymnast’s hip, combined with high forces, high repetitions, possible inappropriate flexibility methods, and a lack of science-based strength and conditioning being used, the labrum can start to fray and tear.

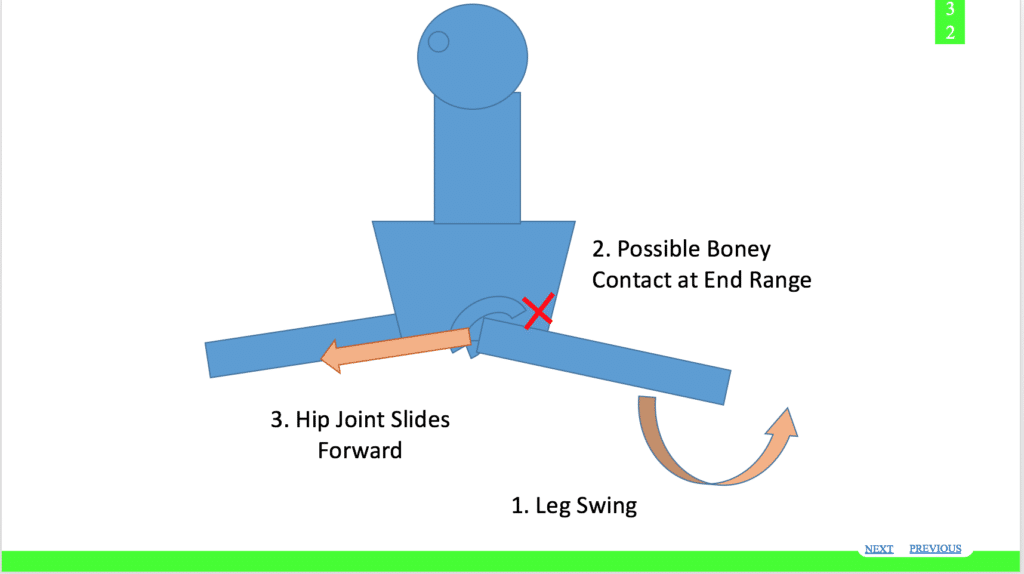

The extreme ranges of motion at end ranges may start to stress the labrum more than its physiological limit. This is something seen with end-range split or oversplit stretching, jumps, leaps, and in bars or release moves. It is also important to highlight a ‘fulcrum’ mechanism of injury presented in the research. This is when the excessive-end range of motion causes the femoral neck and the wall of the hip socket to make contact, and as a result, it ‘tips’ the femoral head out in the opposite direction.

The back leg of a switch leap can be used as an example. If a gymnast continuously swings their leg to end range with lacking control or strength, the back of the femur bone can contact the outside of the hip wall, and cause the ball of the femur to tip forward. This forward motion not only stresses the labrum, but also the iliofemoral ligament, anterior capsule, and musculature like the psoas that is working to prevent this motion. This may also be a common injury mechanism in gymnasts.

It’s important to note that while the labrum can transmit pain, it is not a one-to-one correlation of labral tears equaling pain. Some people have small labral tears and notable pain, while others have notable labral tears and no pain. This is not to say we should ignore labral tears if found. It’s just to say that there are many structures that can become painful in the gymnast’s hip. It is sometimes to determine if pain is coming from ‘inside’ or ‘outside’ the hip joint. This is why skilled medical examination and imaging is crucial.

Smaller labral tears, or labral fraying, may be managed conservatively. Surgeons may want gymnasts to modify their gymnastics workload, avoid end-range motions at high force, and do Physical Thearpy. This PT typically involves managing soft tissue stiffness, reducing pain, increasing glute and deep hip rotator strength, increasing leg strength globally, and then slowly reintroducing higher force running and plyometrics that lead to a gymnastics return to sport phase.

If someone has a more involved labral tear or is having notable pain, a diagnostic cortisone injection may be used. This injection not only helps to confirm if the pain is coming from ‘inside’ the point and the labrum, as well as reduces pain itself. Sometimes the combination of PT and injection can help someone successfully recover.

Sadly, there are some tears that are much larger and much more involved and require surgery. If the tissue has been badly damaged over time, if it is causing the joint to catch or get stuck, if notable pain is occurring, if there are boney abnormalities like cam/pincher lesions, or if possible cartilage damage is occurring, for long term health and performance a labral repair or osteotomy may be needed. For those with significant boney under coverage and hip dysplasia, sometimes a PAO surgery is used as a last resort. These are significant surgeries with 6+ timeline recoveries.

AIIS Subspine Impingement

As mentioned, due to the extreme hip ranges of motions that gymnastics requires, there can sometimes be boney contact between the neck of the femur and the socket of the acetabulum. This ‘impingement’ term can sometimes create injury. In the case of AIIS subspine impingement, during extreme front kicking motions, the bones make contact.

This can cause injury to the bones themselves, but also to the ligaments and soft tissues that are ‘pinched’ in between. Often times the psoas, the rectus femoris tendon, or the underlying joint capsule can become painful.

Lesser Trochanteric Apophysitis (Hip Flexor Growth Plate Irritation)

There are also many growth plates around the hip where certain muscles attach. One of the most commonly irritated within the front of the hip joint is where the hip flexor attaches. The hip flexor tendon attaches to an area known as the lesser trochanter. The growth plate here can easily become aggravated in gymnasts, due to the repetitive nature of the hip flexing motion. The formal name for this is Lesser Trochanteric Apophysitis.

Kips, sprinting, jumps, leaps, and other skills all require lots of this muscle being worked. The boney growth plate it attaches to is not fully matured bone. It’s softer, and as a result less able to handle force. If a pre-pubescent gymnast continues to complain of deeper hip aching with these motions, as well as walking or running, it is worth getting an x-ray to rule out.

Illium Apophysitis (Quad Growth Plate Irritation)

Similarly, the rectus femoris (one of the quad muscles) also attaches to a growth plate on the pelvis. In this case, it is the Illium. The femur bone tend to grow much faster than the quad muscle and rectus femoris tendon can keep up with. This alone created a lot of pulling stress on the growth plate where it attaches on the hip.

When you combine lots of running and sprinting, as well as jumps and leaps, with this rapid growth it can quickly cause the bone to become inflamed. Gymnasts typically will report that when their leg is behind them and being pulled forward very fast (sprinting, coming down from a split jump) they feel pain in the front of their hip. They also may report that during long stretching of splits, the front of the hip in the back leg becomes painful in the same spot.

Stress Fractures

Stress fractures, or fatigue fractures, also can happen in the pelvis and hip of a gymnast. There are many possible contributing factors ranging from doing too much impact too fast, a lack of strength and conditioning being used, nutritional issues, and underlying genetic components related to hormonal profiles.

For any of these reasons and more, the bone itself may start to develop inflammation from being overworked, which is known as a stress reaction. If training continues and rest and PT is not properly used, it can develop into a full femoral stress fracture.

Within these stress fractures are tension-sided and compression-sided stress fractions. Tension-sided stress fractures are located on the outside of the femur bone and are much more serious. This is because if they are not detected early and allowed to rest/heal, they can require surgery to pin back for normal healing. The other subcategory is a compression-sided stress fracture, which occurs on the inside of the hip. While still very serious, it is not an emergent condition.

All types of stress fractures require extended time from compression or use to allow healing, as well as a full workup of general health status (nutrition, genetics, etc) if they continue to reoccur. A full course of physical therapy, exercise progression, and a slow gradual return to gymnastics will be needed.

Hip Flexor/Quad Muscular Strains

Lastly, due to the very unique and variable demands of gymnastics, there are many muscular strains that can occur. The hip flexor, the quad, the TFL, and portions of the groin muscles that help as hip flexors all can become acutely overworked and irritated. This can happen if lots of the same repetitive motions are used, or if someone maybe lacks the underlying capacity to handle high force skills. Sometimes, it can simply happen out of the blue for no reason at all. These tend to only last a week or so, resolve well with rest and light exercise, and tend to not be long-standing issues

Back/Posterior Hip

Ischial Apophysitis (Hamstring Growth Plate Inflammation)

By far and away, one of the biggest hip injuries that plague gymnasts when younger is high hamstring growth plate inflammation. The formal name for this is “ischial apophysitis,” as the ischial tuberosity is the location of the hamstring tendon attachment.

Like the quad, the femur grows much faster than the muscles of the hip/thigh can keep up with, creating excessive tension on the growth plate of the hamstring. Then, we can clearly see that the hamstrings are one of the most used muscle groups in all of gymnastics. It is used for sprinting speed, landing, jumps, leaps, in bars, and more. Also, flexibility work is constantly being worked for lengthening goals or active flexibility.

Due to this, its commonly an injury that can last for multiple months in a row. It’s also common to see gymnasts rest until pain resolves but then not properly go through the exercise progressions and slow, gradual return to sports program. This further creates reinjury and frustration.

All of this high-force jumping and kicking, combined with the constant flexibility work and growth, might create the perfect storm for a gymnast’s growth plate to get very inflamed. And being fully transparent here, I think that the lack of science-based flexibility methods within the gymnastics culture has a bit role to play here.

While the bone inflammation itself is extremely painful and very self-limiting, right next to the hamstring tendon and growth plate is the sciatic nerve. This large nerve branch can also become irritated and start to create notable amounts of pain. To end, it is worth noting that both the sciatic and the hamstring tendon can get over-tensioned if a gymnast’s posture is a bit too over-arched.

A lack of core control, and excessive stiffness in the hip flexors, quads, or anterior groin, can contribute to this anterior pelvic tilt. These all must be screened for and addressed in gymnasts with hamstring issues.

Hamstring Tendinopathy & Hamstring Belly Strain

For gymnasts who are older and have fully closed growth plates, it is typically not the bone that becomes irritated but the actual hamstring tendon. With the same factors as above, and most importantly mismanaged workloads or a lack of hamstring strength capacity, the hamstring tendon can become acutely irritated. The tendon itself can start to change properties, with the collagen not being as strong and durable as it once was due to repetitive micro-injuries.

If the hamstring belly itself becomes strained or irritated, microtears can occur in the tissue. These typically come in strains of Grade I (mild), Grade II (moderate) and Grade III (severe). Like the hamstring tendon, it typically comes with a dramatic spike in sprinting or high-speed workload on the back of a lack of underlying strength and conditioning is done.

These situations typically require a reduction in workload and rest first, followed by slow progressive hamstring loading to promote healing. Then, reintroducing running, jumping, and sprinting occurs. Finally a slow return to gymnastics jumps, leaps, and tumbling can be the final step.

Sciatic Adverse Neural Tension *Rule out lumbar*

While discussing the sciatic nerve and the hamstring, it is worth noting another less common but notable issue some gymnastics deal with – adverse neural tension. In this condition, it is not that the hamstrings lack length or strength, it is that a gymnast is so mobile the sciatic nerve becomes overstretched and irritated. The sciatic nerve starts from the lower back and moves all the way down the back of the leg under the foot.

If a gymnast is doing extreme jumps and leaps and may have an over-extended posture, it can pull quite a bit on the nerve. Often gymnasts will complain of numbness, tingling, and traveling sensations. This can be managed with a postural correction to reduce the over-extended pelvis, nerve gliders, and workload modification. We definitely want to rule out any lumbar disc pathology in this scenario prior to assuming adverse neural tension. This can be done with a repeated lumbar extension movement screen, checking for centralization of symptoms.

Inside/Medial Hip

Hip “Impingement” or FAI

One of the most common hip injuries that have become more popular in the last 10 years is impingement. The technical term for this is Femoroacetabular Impingement or FAI, and simply refers to the bone of the leg (femur) making contact with the boney socket of the pelvis (acetabulum). While this happens all the time, sometimes when excessive or repetitive, it can cause pain due to the compression of tissues of the hip like the labrum, joint capsule, or muscle/tendons.

When this happens, sometimes overlapping pain can occur in the hip both in the front, as well as the middle/groin. Sometimes it is described as a ‘pinch’ and other times it creates lots of achiness and soreness during daily life. Flexing the hip up, and crossing the legs, both tend to be the most irritating factors.

In most sports, deep squatting and explosive running or pivoting can sometimes create this irritation. In my experience, I tend to find that the microinstability and extreme ranges of motions in gymnastics mentioned above are the primary triggers for labral irritations in gymnasts. However, it is possible that other issues might start to come up during squatting and other motions that involve hip flexion. The key here is to figure out which skills or motions are the most provocative, and treat those first.

Inferior Microinstability

Gymnasts, dancers, and other hypermobile athletes can get a unique type of inside groin pain from extreme ranges of straddle (or abduction) motion. Sometimes, when the leg is moved into an extreme straddle position, this can create abnormal boney contact between the outside of thigh bone and the outside of the pelvis. Just like when the leg is extended very far behind it can cause pain in the front of the hip, sometimes when the leg is straddled very far to the side it can cause in the underneath groin area.

The thought here is that the extreme range of motion is causing the ball of the femur to move downward, putting pressure on the underside hip ligament (the pubofemoral ligament), as well as the labrum. To rule this in, a side-lying hyper abduction test and MRI can both help determine if this is occurring.

Adductor Strains

The high force, high repetition, and high range of motion nature of gymnastics causes a ton of stress to be placed on the groin muscles. While many people only view the groin muscles as things that pull the legs together (which they do) the reality is that the groin muscles are also very active in other motions. Gymnastics requires a ton of different stresses on these groin muscles due to the different jumps, leaps, and skills that put the hip in a variety of motions.

Due to this, the groin muscles can easily get strained with training these different skills day to day. Often times skills like switch sides, stalders, and straddle jumps all tend to be the highest risk here. These typically are felt with more active motions like walking and lifting the leg during the day, and not as many passive motions.

Snapping Hip Syndrome

Normally in the hip, due to how many different structures exist in a close space, there are a lot of tissues within layers of the hip outlined above that slide and glide over each other. This happens every day and all the time, usually without pain.

However, sometimes with excessive or repetitive rubbing, certain tissues can become painful and irritated. One common situation this comes up with is when the hip flexor tendon rubs back and forth over a boney prominence called the lesser trochanter. This is called “internal snapping hip syndrome” and many gymnasts feel it when they move their leg from a flexed to an extended position (v ups, leg lifts, stalders, et). Another version of this excessive rubbing of tissues can occur between the Iliotibial Band and Greater Trochanter, called “External Snapping Hip Syndrome”

While not always the worst thing, it can become irritative and limit practices. Often times soft tissue work, stretching, and strengthening around the hip is the most effective strategy to help out.

Outside/Lateral Hip

Glute Med Tendinopathy w/ Trochanteric Bursitis Caveat

On the outside of the hip, there are quite a few structures that are important for single-leg landings, running power, and lifting the hip in gymnastics skills. Due to this, they can sometimes be the source of pain. 10 years ago, one of the most common structures believed to cause pain was a bursa on the outside of the hip that helps to reduce friction between the outer hip bone and the glute med muscle on top of this. Trochanteric Bursitis was the common diagnosis.

As years have gone on, and more research has surfaced, it’s now thought that it’s not so much the bursa, but the tendon of the glute med above it, that might be the main source of problems. When considering other areas of the body that can get painful tendinopathies from overload, this makes sense. With so much force, repetition, and stress placed on the lateral glute muscles (particularly when it isn’t always a focus of strength work) irritation may surface.

If someone is having a lot of pain with these motions and finds themselves unable to perform well on one leg due to lateral hip pain, consider glute med tendinopathy.

Lateral Wall Impingement

As stated above, with straddle jumps and excessive lateral hip motions in gymnastics, the outside of the hip bone may bump into the outside of the hip socket. This lateral wall impingement may present as groin pain if the head of the femur moves downward. But, in other cases, the pain may be felt on the outside of the hip joint if bone bruises develop on the bones that are being contacted together. This typically can be seen on xray or MRI. It should be mentioned that sometimes labral pathology can refer to the outside of the hip (a “C” sign) and must be considered as well.

Deep Hip rotator Strains or Piriformis Syndrome

Lastly, there are many muscles deep within the hip that play a huge role in not only running/jumping, but also lifting and rotating the hip during jumps, leaps, stalders, and other skills. Like any other muscle, if under-trained and overworked, they can become strained and painful. Often times this is felt as deep buttock pain, just behind the outer hip bone. Many of these muscles attach to this outer hip bone, or near it, so pain is often felt here. Manual muscle testing of these areas, as well as imaging, can be used to diagnose this.

How Long Do Low Hip Injuries Take To Heal?

Respecting The Body’s Healing Process

The question that I get from gymnasts most when treating them for back pain is – “when can I go back to gymnastics?” or “can I compete?”. I completely understand athletes wanting to get back to training as fast as possible. It was the same for me as an athlete, and the coaching side of me certainly knows the challenge of having an athlete at practice hung up by these injuries yet wanting to make progress.

That said, we can not magically speed up basic human biology. There are certain things we can do to accelerate, assist, and enhance the natural healing process. But at the end of the day, we have to understand and respect the body’s healing timelines. There is a base timeline for various tissues of the body, and when looking at the literature a realistic timeline for various degrees of injuries. Unfortunately, these don’t change even if we are in the middle of competition season or ahead of a very exciting opportunity.

In almost all cases, taking the time to allow full healing and rehabilitation is the better choice. I’ve been fortunate to work with a few of the world’s best elite and Olympic-level gymnasts/coaches, and I can tell you that the situations where someone has to ‘push through for their ultimate goal are few and far between. They occur, but very very rarely. Not to mention, these decisions are often made by adults, their parents, and their medical providers as a team. With this in mind, let’s review some timelines for these various injuries.

Timeframes and Variability for Hip Injuries

We must keep in mind that while there is great science on the healing timelines for many common back injuries, there is still a huge variability that can occur. In the big picture, factors like age, genetics, skill level, genetics, past injury history, and more all play a role. Also, the severity and reoccurrence of the injury will make a huge difference in the overall healing timeline. Also, as you can see above, there is a huge spread in the different types of movements that cause pain, the skills that are involved, and what structures might be irritated.

Oftentimes I will hear people compare one gymnast’s injury to another. Saying that “X” hip injury took 4 weeks in one person, so a sort of similar “Y” injury in another person will be the same. I strongly recommend people do not do this. Even with what seems like the exact same injury, say stress reaction or muscle spasm, due to many factors mentioned above and more the full return to gymnastics could be wildly different.

A hip flexor strain in a 12-year-old Level 7 female gymnast who can change their beam leap from a switch leap to a straddle, and switch to a Tsuk instead of a Yurchenko, might have a much easier time of healing and get back to gymnastics compared to 15-year-old Level 10 female gymnast who has to do a switch ring and Yurchenko. Not to mention one hip flexor strain reaction may be completely different from another in terms of the structures involved, outside gym factors, and inherent anatomy differences between athletes. One could simply just be the hip flexor strain, while another could be the capsule and labrum also strained.

My best advice is to follow the science of healing timelines (and physician/surgeons protocols when appropriate) but use the major milestones of healing as a guide. These include education, mitigation of pain, restoration of mobility, a return to daily activities, return of full strength/power, and the ability to tolerate all advanced plyometric skills. I also always teach people early in the rehab process that during the middle of a rehab, when their pain may be gone, they will want to go back to sports but we have to resist the urge. Building strength, power, and capacity take multiple months and lots of work.

A useful rule of thumb to use with people is that for however long a gymnast is out of practice with their injury, it will take 2-3 times as long to return. So say someone has a mild muscle strain that keeps them out for 2 weeks, it will likely take them 4-6 weeks more to fully return. If someone has a stress fracture that keeps them out for 3 months, it will likely take an additional 3-4 months to get back fully.

This being said, in my experience and based on the scientific literature, with less severe injuries like muscular strains and low-level joint irritation, it could be very benign and only take 2-4 weeks to recover.

As the severity of the injury progresses, the timelines extend. With higher degrees of muscular strains, disc or nerve issues, or stress reactions, the timeline may extend into the 4-8 week range.

Lastly, the most severe injuries occur like full spondy fractures, sciatica or significant nerve pain, end plate fractures, and decompression surgeries may easily take 4-6+ months to recover from.

The 4 Phases of Rehabilitation & Goal Milestones For Recovery

When I lecture, do consulting work, or provide rehabilitation for gymnasts, I always try to outline these 4 phases general of rehabilitation. Regardless of the injury, all athletes progress through them. Some injuries move fast if they are less severe, and some move much slower if they are more severe.

Also, for me recovery refers to fully getting back to gymnastics without physical or mental hesitancy. Being ‘cleared’ by a medical doctor from a tissue healing point of view doesn’t necessarily mean being fully ready to return to full gymnastics practice. I know and work with many amazing gymnastics-based medical providers, but I know not everyone has this luxury. This is why I try to abide by the 4 Phases of Rehabilitation. They are as follows,

1. The Acute/Subacute Phase – “Put The Fire Out”

This first initial phase is all about trying to understand why someone is in pain and reduce their symptoms while also helping educate them about what’s going on. This is generally in the first 4-6 weeks.

We have to make sure that we really follow a good evaluation process by talking to someone, and also going through an in-depth movement assessment. I spend a long time when I first meet someone listening to their story and figuring out which category of hip pain they fall into. It’s crucial that. understand what the injury is, and in some cases, if they need follow-up imaging or to visit with a hip doctor first. From there, once we have. a good working theory I aim to do the following to help them get out of very high levels of sensitivity and pain.

Reduce Hip Workloads

This is what no gymnast, coach, or parent wants to hear, but it’s a reality. The truth is, if someone is going through quite a bit of hip pain and they are at the point where they are seeing a medical provider, there will likely be no “magic exercise” or “perfect stretch” to get their problem to go away. These types of injuries tend to slowly progress over time, so they will take time to calm down. Our brain oftentimes turns up sensitivity levels to movements in an effort to protect us.

So, we want to first talk about the need to think in “weeks and months” not “minutes and days.” Gymnasts will need to take a break from skills or routines, even if in the middle of the season sometimes. The hip tends to need time away from splits/oversplits, jumps, leaps, sprinting, and possibly straddling motions.

Maintain Global Activity Level

This said the research is clear that complete rest might not be ideal for hip pain. We want to encourage a gymnast to do what they can to maintain activity levels. For some that might be no gymnastics at all, but going for walks and basic exercises from PT. For others, that might be no actual event work but still doing strength, physical preparation, and basic flexibility work for the core and upper body.

It is hard to know for sure, as each case is different, but if possible we want to reduce the exposure to skills that cause pain while trying to maintain as much activity as we can. A skilled medical provider can work with a coach and a gymnast to create this. There are also some great tools that rehab providers may be able to use here like Blood Flow Restriction training.

Educate on Hip Irritatants in Daily life

Oftentimes, gymnasts don’t realize that things during their daily life might be contributing to their pain. Even though their pain might have started with things like jumps, leaps, or specific gymnastics skills, after a flare-up there might be day-to-day things that need to be modified. In particular, things like sitting in deep chairs/couches, or crossing the legs, might be aggravating. Also, excessive time sitting, driving, or walking might create some problems. For this, educating gymnasts about these things and helping them be aware of them can help alleviate the initial pain.

As you can see here, it’s crucial that we know why someone has pain so that we can help them do the opposite. It may not be an instant fix, as sometimes the first 7-14 days can acute pain that is more chemical inflammation in nature, or acute guarding, that doesn’t respond super well to any motion. In this case, I tell gymnasts to do whatever they can to be comfortable, maintain a regular routine of switching positions, and to start PT ASAP for pain relief strategies.

Maintain Local Core Activity Levels

There is really interesting research from Stuard McGill and others that when someone has an acute bout of hip pain output, the activity levels of muscles within glutes and other hip muscles. In an effort to help protect the hip, or reduce activity, certain muscles might be downregulated. Also, someone might change the way they walk to avoid loading sensitive structures.

With this in mind, I believe that trying to maintain as many activity levels (while in a safe context) is crucial. As long as someone is not having an increase in symptoms during or in the few days following PT, I will try to give them neutral basic hip and core exercises. Things like low resistance clamshells, bent knee side planks, sideband walks, and hip lifts. I don’t think we are getting someone stronger necessarily, but more keeping them active and trying to maintain load in the hip/core/lower back. In the pain science literature, it is thought that maybe this helps to reduce the acute sensitivity levels over time along with proper education strategies.

I also tend to give people 90-90 breathing and core bracing drills for their core. Then, I try to get them to bird dogs, dead bugs, bent knee side planks, bent knee front planks, and 1/2 kneeling anti-rotation press-outs. I find that these tend to be tolerated better as they are in a move relatively neutral position, and lower threshold.

Address Issues Above or Below The Hip

One of the most common things I see missed in gymnastics hip pain rehabilitation is not looking at the whole body. As we broke down above, the core, and ankles may play a huge role in hip pain. While a gymnast might have pain at their hip joint, the issue could truly be above or below what is causing their pain. Just treating someone’s hip pain, but not looking at their entire body or their training program, is like trying to put out a fire by simply pulling the smoke alarm batteries out. While it may make the alarm turn off, it hasn’t actually fixed the issue. The hip joint and the core/pelvis are truly inseparable in the way that they function.

If a gymnast really struggles with core control/core strength mobility, or maybe isn’t as strong as they need to, or maybe doesn’t have the best technique during skills, that must be addressed. I always spend a significant amount of time breaking down the core, pelvis, and ankles for mobility or strength issues. I also talk a lot with them about their technique and watch videos to see what might be going on. During the acute phase of hip pain, when someone may be limited, this is the perfect time to clear these issues up.

Manual Therapy & Modalities

There is a huge debate out there on if manual therapy and things like heat are useful or a complete waste of time. This blog is not the time to debate this, but I will say that while not the main focus of my treatment compared to education and exercise, I do use both. In the very acute phase, we are looking for any way to reduce sensitivity levels and calm down someone’s back. If 5-10 minutes of heat and manual therapy make a patient feel and move better, and it allows them to tolerate exercise better, I’m all for it. That said, I try to move to exercise work as fast as possible.

2. The Intermediate Phase – “Be A Human Again”

This phase of rehab, generally in the 4-6 to 10-12 week mark, is about progressing exercise programs to build local hip and global capacity. We want to use exercise and ongoing education as our main tools to help rebuild their capacity. At this point, if workloads have been reduced and the time has been put in place, gymnasts are starting to feel a bit better. In some more significant situations, like extensive labral tears or more intense stress fractures, it might still take a bit to feel great.

Progress Hip and Global Exercise

The first, and most important, the task is to make the exercise program harder. This not only allows us to physically load the hip and core structures more but also helps rebuild mental confidence. A gymnast wants to know that their hip can handle harder exercises, and higher forces, without increasing symptoms. Personally, for direct hip loading, I like

- Side plank clamshells

- Side plank leg lifts

- Lateral band walks

- Reverse/Sideways band walks

- Single leg hip lifts/glute bridges

- Prone hip external rotation

-

- Split squats

- Low box Step-ups

- Elevated kettlebell deadlifts

- Box goblet squats

- Physioball curl ins

- Sled push/pulls.

-

- Bear crawls

- Wall press dead bugs

- Full side planks

- Front plank drag throughs

- Suitcase carries

- Farmer carries and suitcase carries

Restore Passive Hip Range of Motion

We want to make sure that we restore full hip motion. For one, we want a gymnast to feel safe and comfortable knowing that they can move their hip in all directions which will eventually be used in skills. This is the first step in making sure we have this motion available so that in the next phase we can progress back to more explosive power work and basic gymnastics skills.